- Division of Marine Fisheries

In 1925, following several shellfish-related illness outbreaks including the nation-wide typhoid scare in 1924 where tens of thousands of people became ill following the consumption of oysters, the US Public Health Service closed shellfish growing waters around the country. These closures were implemented near every city and town where it was then the normal practice to dispose of our sewage—untreated—into the nearest waterway. In heavily populated and developed states like Massachusetts, these closures were particularly widespread and impactful.

Because it would be several decades before wastewater treatment became a common practice, attention focused instead on making shellfish harvested in contaminated waters safe to eat to help revive local shellfish industries. As filter feeders, molluscan shellfish can concentrate pollutants up to 100 times that of the level in the surrounding waters making them a perfect means to transmit pathogenic organisms found in sewage to people. Shellfish practitioners at the time wondered if this same biological process could be reversed by immersing them in purified water to naturally purge the contaminants until they were safe to eat. After a series of experiments validating the process known today as depuration, the first ever shellfish “purification” facility in the country was opened in 1928 on Plum Island by the City of Newburyport.

Following several decades of successful depuration of local softshell clams, the City of Newburyport transferred ownership of the Plant to the Division of Marine Fisheries in 1961 which has operated it ever since to treat clams from around the state. However, in November 2023, a severe coastal storm eroded nearly 300 feet of the coastal dune complex that protected the Plant and its saltwater well system, making the facility inoperable. With the primary dune no longer in existence, subsequent storms flooded the Plant itself causing further damage and uncertainty.

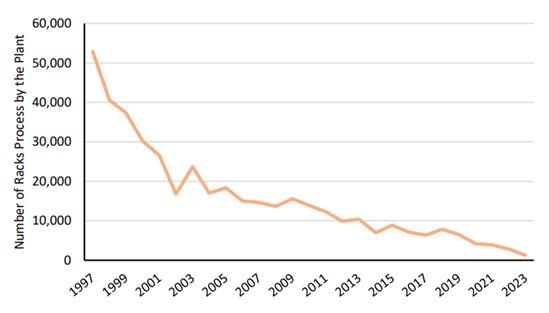

DMF responded by instituting an economic relief program for affected fishers to replace lost wages during the period of the Plant closure and commissioning an engineering study to investigate the feasibility of restoring operations of the Plant and assessing its long-term viability given its vulnerable location. Unfortunately, while the study did determine that its seawater system could be reconstructed and the plant re-opened at a cost of roughly $700,000, the extreme vulnerability of the Plant would make operations there highly uncertain and would likely require retreat from the location within the next 20–25 years. When coupled with the dramatic decline in the amount of clams processed at the Plant in recent years, the Commonwealth made the difficult decision to close the Plant permanently in December 2024.

A central consideration in the decision to close the Plant was the impact on the 100-year legacy of the contaminated softshell clam fishery of Massachusetts and the people dependent on it. Fortunately, the only other depuration plant in New England is located just 25 miles away operated by Spinney Creek Shellfish Company in Eliot, Maine. To help Massachusetts fishers switch to this alternate facility, DMF instituted a program to cover 100% of the cost and time differential between use of the two facilities which allowed the fishery to re-open in February 2025.

Another consideration regarding the future viability of contaminated harvest in Massachusetts is that with the continued enforcement of our laws against water pollution, there should be less need for depuration over time. Indeed, DMF is currently planning to re-classify large swaths of the areas that formally required depuration in the outer Boston Harbor region in the towns of Hingham, Hull and Winthrop which will allow clams to be sold directly into commerce. This upgrade will represent the final phase of the multibillion-dollar Boston Harbor cleanup which has been a major victory for the marine resources of the Commonwealth.

Although this trend will result in less contaminated shellfish growing areas over time, we anticipate that there will always be a need for some amount of depuration in certain coastal areas impacted by rivers and aging wastewater infrastructure so this unique fishery can continue. Having partners like Spinney Creek coupled with continued improvements in water quality represent a win-win for shellfishing in Massachusetts!

By Wayne Castonguay, Regional Shellfish Supervisor