Key challenges and future needs in Berkshire County

- This page, Berkshire County Housing Snapshot, is offered by

- Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities

Berkshire County Housing Snapshot

Berkshire County Housing Overview

The Berkshire County region contains 32 cities and towns with village centers, downtowns, neighborhoods, and cultural institutions nestled among scenic rural and forested areas. While the region is more rural in character than much of the state, it is also home to the Gateway City of Pittsfield. Once an industrial powerhouse, the county has seen declines in both population and jobs since the 1970s, slowing housing demand as well as people’s ability to afford the homes that are available. Homes cost less than they do in Eastern Massachusetts, but incomes are lower: only 21% of Berkshire County renters earn over $75,000 per year, as compared to 40% of renters statewide. The region still experiences substantial rates of cost burden: one in four renters is severely cost burdened, and one in ten homeowners.

In Berkshire County, the median sale price for single family homes and condos rose from $295,000 in 2012 to $518,900 in 2021 – a 76% increase. While prices are rising, demand is still not strong enough to drive substantial development: only 1,500 new homes were built in the last 10 years – just a 2% increase in housing units.1 Only 1.4% of homes in Berkshire County are available for sale or rent, just below the statewide average and well below a “healthy” vacancy rate that allows for people to find homes when they need to move. In some towns there are effectively no homes for rent

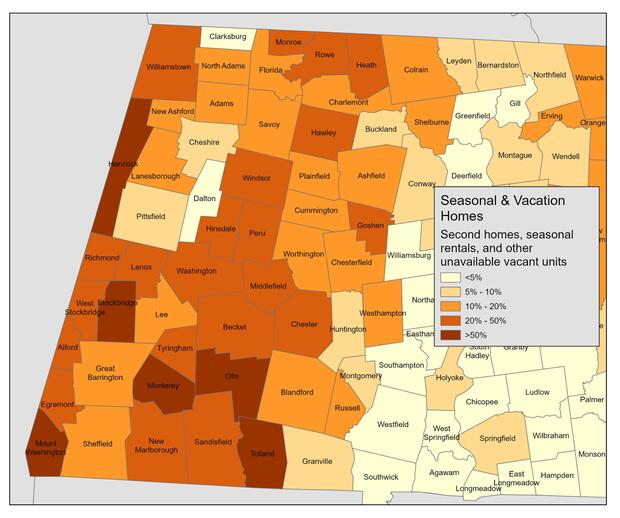

Berkshire County is a popular tourist destination and this is reflected in the share of housing units that are seasonally vacant, approximately 12% of the total housing stock, the highest share outside the Cape and Islands.2 In many towns, seasonal and vacation homes exceed 25% or even 50% of all units. Seasonally vacant homes are not available for year-round resident use and can put pressure on the remaining year-round housing stock. Many communities also experienced an influx of residents purchasing homes or moving into second homes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Long term effects of this influx have yet to be determined.

Affordable housing development has also been slow, and deed-restricted units continue to be scarce. Only two municipalities in the region have met the state’s 10% affordable housing goal. Nonprofit housing developers report a variety of factors that make it hard to build lower-income units. Due to the relatively low AMI, rental income from even moderately affordable units (80%) is often insufficient to make the financing work. [This challenge is reportedly compounded by cost standards required for LIHTC funding.] The regional housing plan includes several strategies for how to educate residents about affordable housing needs and advocate for more financial resources, support services, and new development.

Much of the region’s current housing stock is aged and in need of investment. About 65% of housing was built before 1970 compared to 57 % statewide.3 Many homes do not meet current or modern building code standards and require significant financial resources to rehabilitate. Some of the region’s communities have enacted local rental inspection programs (Adams, North Adams, and Williamstown), and the regional plan recommends other municipalities do the same. The Abandoned Housing Initiative and the Regional Housing Rehabilitation Program are designed to help get housing back online.

Recent reports highlight a rise in speculative purchases by investors to transform homes into short-term rental properties, compounding the already prevalent issue of limited quality year-round housing supply in the region.4, 5 The regional plan encourages municipalities to explore fees such as Room Occupancy Excise Taxes on short-term rentals, directing the revenue to affordable housing.6 Some Berkshire municipalities have implemented additional restrictions on short-term rentals. For example, Great Barrington restricts corporate ownership of short-term rental properties among other stipulations. These policies may increase the supply of year-round housing by discouraging the intense forms of short-term renting but are still in their infancy and their impact is not yet fully understood.

Public infrastructure capacity (water, sewer, electrical utility lines) presents significant challenges for new housing development. In the Berkshires, only about 4.6% of vacant land is served by public utilities.7 Furthermore, the region’s topography and presence of critical natural resources results in a tension between housing development and conservation. 8 The region’s municipalities are challenged to work with private developers to strategically site new developments in areas that are most efficiently served by public infrastructure; denser developments in existing centers will be key to preserving the region’s unique landscapes and historic development patterns.

Berkshire County Future Housing Needs

Berkshire County’s population has been declining for decades, having fallen 7.5% from 1990 to 2020. All three of the population scenarios prepared for this plan anticipated continued declines in population, ranging from -8.0% for the low-growth scenario to -2.8% for the high-growth scenario. The high-growth projections assume increased population growth statewide, and in particular higher growth rates among lower-cost regions such as Berkshire County.

The region isn’t likely to see as drastic a decline in households, due to the aging of the population and more single person households. The mid-range scenario (Competing and Growing) forecasts household decline -0.7%, or about 400 households. The chart to the left shows households by age for that scenario. These projections anticipate a net decline of 3,100 households headed by someone under the age of 75, and an increase of 2,700 in the number of householders 75 and over—a 30% increase. This will create significant needs for senior housing and services in the region.

Most of the net growth in older households is projected to be low-income older adults living alone, a segment projected to increase by 700 households. The number of non-senior householders is projected to decline across all income groups.

Help Us Improve Mass.gov with your feedback

Thank you for your website feedback! We will use this information to improve this page.

If you would like to continue helping us improve Mass.gov, join our user panel to test new features for the site.