- Scientific name: Eulimnadia agassizii

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

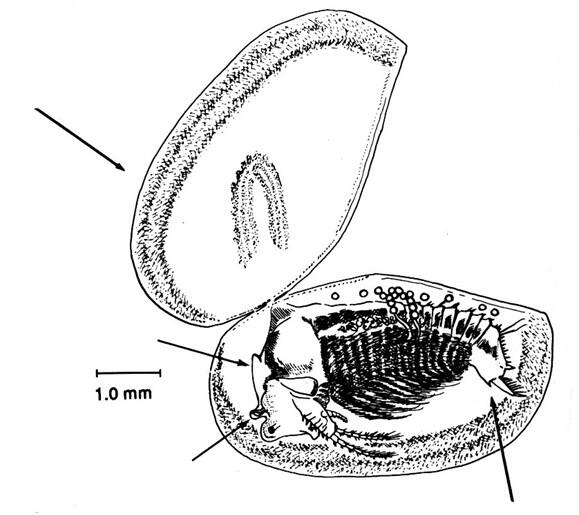

Agassiz’s clam shrimp (Eulimnadia agassizii), Image by Steve Johnson.

Agassiz’s clam shrimp is a small crustacean from the class Branchiopoda that resembles a mollusk because it is enclosed in a bivalved structure called a carapace. The egg-shaped carapace is transparent, ranging in color from clear to brown. It consists of two shell-like valves that are connected by a fold, each with 4 and occasionally 5 growth lines. The valves enclose the head and eyes, body, and feathery appendages. Specimens of Agassiz’s clam shrimp can reach up to 9 mm (0.35 in), but examination of specimens from one population reached only ~6.0 mm (~0.24 in).

Two other species of clam shrimp in the class Branchiopoda are quite similar to Agassiz’s clam shrimp. The Holarctic clam shrimp(Lynceus brachyurus)from the order Laevicaudata is a more commonly encountered clam shrimp. This clam shrimp is light orange in color, without growth lines on its carapace, and with a smaller, more rounded appearance. The Holarctic clam shrimp is found in larger, more persistent ephemeral freshwater habitats. A dissecting scope is needed to differentiate Agassiz’s clam shrimp from another species in the same order Spinicaudata, the American clam shrimp (Limnadia lenticularis). The American clam shrimp is also translucent in color, is less narrow and more rounded, has 7 to 18 growth lines on its carapace, and is larger at an average of 10 mm (0.39 in). The American clam shrimp occasionally co-occurs with Agassiz’s clam shrimp. Identification guides sufficiently illustrate the differences between these three species (Smith 2000).

Life cycle and behavior

Agassiz’s clam shrimp has a short life cycle, evolved to suit the ephemeral nature of its habitat (e.g., <1-2months). When environmental conditions are met in their pool habitat, including sufficient water levels and temperature, Agassiz’s clam shrimp hatch from resting eggs or cysts. The eggs are actually developing embryos with a covering for protection from heat, freezing, and periodic dry conditions. After hatching, juveniles reach sexual maturity in 8-9 days. Populations are considered androdioecious, composed of either all hermaphrodites, or a combination of males and hermaphrodites, although males are rare (Weeks et al. 2005). “Females” (hermaphrodites) carry resting eggs between the body and the fold of the carapace, and they are shed as the adult molts.

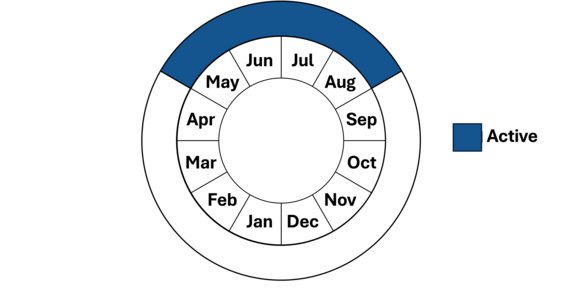

Adults begin to die shortly before the shallow pool dries or they die stranded as the pool dries. Typically, only one generation per wet period is produced before pool desiccation. The resting eggs remain dormant until the appropriate environmental conditions are met, which could take years. The Agassiz’s clam shrimp is not found consistently year after year in the same shallow pool and its presence fluctuates depending on environmental conditions. Agassiz’s clam shrimp is active from May to September in Massachusetts.

Like all clam shrimps, this species swims with the fold of its carapace pointing up and its appendages pointing down to aid in locomotion, respiration, and feeding. The American clam shrimp swims, using a paddling motion created by the second antennae. If they cease to paddle, they tip on their side. They are most often found moving along the pool bottom in vegetation (Thorp and Covich 2001). This species is a filterer-collector and feeds by drawing water into the carapace using its feathery appendages to collect food particles.

Distribution and abundance

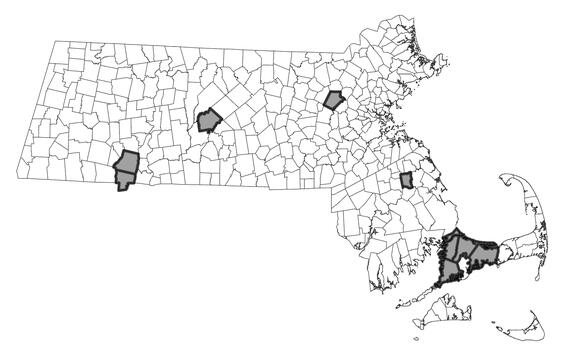

Agassiz’s clam shrimp has been sparsely recorded in Ontario, Florida, Virginia, New York, Connecticut, and Massachusetts. In Massachusetts, the species occurs on Cape Cod, the Connecticut, Ware, Concord, and Taunton River watersheds. Recent observations expanded the known range of this species and likely occurs in more locations across the state where suitable habitat exists. When present, hundreds to thousands Agassiz’s clam shrimp can be found in a single pool. Samples from most pools are entirely composed of hermaphroditic individuals and consequently have presumed reduced genetic heterozygosity and allelic diversity because of inbreeding and founder effects. Pools with males have been observed and are presumed to have higher levels of heterozygosity (Weeks et al. 2005).

Little is known regarding the status of Agassiz’s clam shrimp in Massachusetts. It is very rare in eastern North America and is listed under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act as Endangered. All listed species are protected from killing, collecting, possessing, or sale from activities that would destroy habitat and thus directly or indirectly cause mortality or disrupt critical behaviors. In addition, listed animals are specifically protected from activities that disrupt nesting, breeding, feeding, or migration.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Agassiz’s clam shrimp inhabits ephemeral (vernal) pools, typically with shorter hydroperiods (weeks to months), shallow depths, and underlain by sandy substrates. These depressions can hold water in the fall, late winter and spring, but also during the summer after precipitation events when Agassiz’s clam shrimp are active. Otherwise, these pools are dry. The species has been recorded from flooded field depressions (Smith 1995), unpaved road depressions (i.e., puddles), and other ephemeral pools (Zinn and Dexter 1962).

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Typical ephemeral pool/puddle habitat for Agassiz’s clam shrimp. Image by Steve Johnson.

Threats

Pools that support the Agassiz’s clam shrimp are usually dry many months of the year, making these habitats easy to overlook. Losses of these pools to development, draining, filling, or contamination from pesticides or toxic substances have the potential to threaten this species. Hydrologic alterations (e.g., water withdrawals) may interfere with length and timing of habitat inundation and could cause local population extinction. Impacts to surrounding riparian areas, including development and colonization of invasive plant species, are also a threat to pool connectivity, water quality, and pool habitat degradation.

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

Standardized surveys are needed to update the population status of Agassiz’s clam shrimp at its historical sites. Survey effort should also target unsampled vernal pools and depressions with physical features that may support Agassiz’s clam shrimp – it’s likely the species occurs in other watersheds across the state. Surveys should target adults when pools are filled by precipitation events generally from May to September and likely requires multiple visits to increase detection. Monitoring efforts are recommended at least every 5-10 years or as needed to the extent practical (e.g., in response to potential disturbance or stressor events) at high-quality sites.

Management

Protection of Agassiz’s clam shrimp pool habitat is critical for its persistence in Massachusetts. Routine disturbances may benefit this species in some landscape contexts to maintain pool habitat and discourage succession of plant species encroaching from adjacent areas, particularly invasive species. Creation of new pool habitat may be warranted in suitable areas where depressions need to be filled (e.g., functional roadways) or to restore extirpated populations.

Research needs

Surveys should continue to target historical but also identify new pools to better understand its distribution, relative abundance, and habitat requirements in Massachusetts. Other research needed for this species include identification of environmental thresholds that trigger cyst hatching including precipitation amounts and water temperature. Increased knowledge of the longevity and size of cyst banks, genetic isolation, and persistence and viability of pools composed of all hermaphrodites would inform population stability and risks to environmental stressors.

References

Belk, D. 1989. Identification of species in the conchostracan genus Eulimnadia by egg shell morphology. Journal of Crustacean Biology 9: 115-125.

Smith, D.G. 1992. A redescription of types of the clam shrimp Eulimnadia agassizii (Spinicaudata: Limnadiidae). Trans. Am. Microsc. Soc. 111 (3): 223-228.

Smith, D.G. 1995. Notes on the status and natural history of Limnadiid clam shrimp in southern New England. Anostracan News 3 (2):3-4.

Smith, D.G. 2000. Keys to the Freshwater Macroinvertebrates of southern New England. Published by author. Sunderland, MA. 243 pp.

Weeks, S.C., R.T. Posagi, M. Cesari, and F. Scanabissi. 2005. Androdioecy inferred in the clam shrimp Eulimnadia agassizii (Spinicaudata: Limnadiidae). Journal of Crustacean Biology 25(3):323 – 328.

Zinn, D.J., and R.W. Dexter. 1962. Reappearance of Eulimnadia agassizii with notes on its biology and life history. Science 137 (3531): 676-677.

Contact

| Date published: | March 7, 2025 |

|---|