- Scientific name: Bombus pensylvanicus

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

American bumble bee (Bombus pensylvanicus)

The American bumble bee (Bombus pensylvanicus) is relatively large, the queen 22-26 mm (0.9-1.0 in) long, worker 13-19 mm (0.5-0.8 in), and male 15-21 mm (0.6-0.8 in) (Williams et al. 2014). Color pattern is as follows: the face and upper side of the head are black (occasionally gray in the male); the front of the thorax (just behind the head) is always yellow, contrasting with both the head and middle of the thorax, which is black (occasionally gray); the rear of the thorax is usually black, but may be gray or partially yellow. In the queen and worker, the front two thirds of the abdomen is yellow, contrasting with the rear one third, which is black. The abdomen of the male is almost entirely yellow, typically (though not always) with orange at the tip. The northern amber bumble bee (Bombus borealis), which may occasionally occur in northern Massachusetts, is distinguished from the American bumble bee by its yellow face and upper side of the head. When the American bumble bee is black or gray on the rear of the thorax, it may be confused with the yellow-banded bumble bee (Bombus terricola). However, upon close examination, the American bumble bee has a head that is longer than wide (opposite in the yellow-banded bumble bee); shorter antennae than the yellow-banded; and the queen and worker do not have yellow hairs at the tip of the abdomen, as is typical in the yellow-banded (Williams et al. 2014). The male American bumble bee may be confused with the yellow bumble bee (Bombus fervidus). However, the American bumble bee is black on the sides of the thorax (yellow in the yellow bumble bee), and has orange at the tip of the abdomen, which is absent in the yellow bumble bee.

Life cycle and behavior

Like all bumble bees, the American bumble bee is active throughout the growing season. The queen overwinters, emerging in the spring to start a new colony. Workers become increasingly abundant through late summer and then begin to decline as males emerge in late summer and early fall. Queens of the American bumble bee begin activity later in the spring than most other bumble bees (Grixti et al. 2009), a trait that may confer greater susceptibility to decline (Williams et al. 2009).

Distribution and abundance

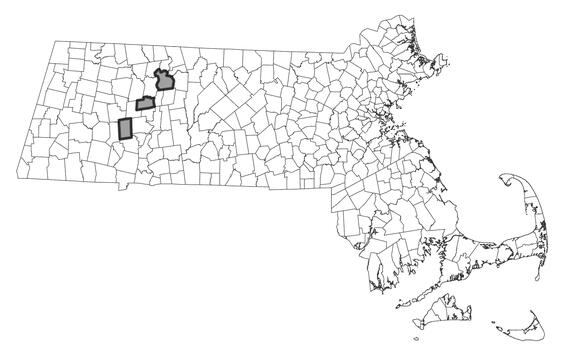

The American bumble bee is a southern species, in eastern North America ranging from southern Maine south to Florida, and west to Montana and Arizona; it is absent from much of the Mountain West but found on the West Coast in Oregon and California (Williams et al. 2014). In Massachusetts, recent records of this species are restricted to the Connecticut River Valley.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

As a group, bumble bees are generalized in habitat requirements and floral resource needs as compared to many other bees. However, the American bumble bee is a long-tongued species dependent on plants with long, tubular flowers for nectar. The American bumble bee may be found in grasslands, fields, pastures, and other farmlands, as well as suburban yards, parks, and gardens. However, habitat must provide a diversity of flowers blooming throughout the growing season. Within such habitat, this species typically nests on the ground surface in tufts of long grass or piles of cut grass or hay (Williams et al. 2014).

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

The American bumble bee is in decline in the northern parts of its range (Grixti et al. 2009, Cameron et al. 2011, Williams et al. 2014, Colla 2016). In Massachusetts prior to 50 years ago, the American bumble bee occurred in the Connecticut River Valley of Franklin, Hampshire, and Hampden Counties, as well as in Middlesex, Norfolk, and Suffolk Counties, and in the southeastern part of the state in Plymouth County, on Cape Cod, the Elizabeth Islands, and Martha’s Vineyard. It has since declined dramatically, now found only in the Connecticut River Valley, where it is very rare. Threats potentially affecting the American bumble bee in Massachusetts include: (1) pathogens introduced via commercially propagated bumble bees; (2) habitat loss or degradation, including loss of native floral diversity to adverse landscaping practice, agricultural intensification, succession and afforestation, or excessive deer browse; and (3) pesticide use where habitat overlaps or interfaces with agricultural or landscaped areas.

Conservation

Land protection and habitat management are the primary conservation needs of the American bumble bee in Massachusetts. This species needs open habitats with a diversity of flowers blooming throughout the growing season.

Survey and monitoring

The distribution of the American bumble bee in Massachusetts is well relatively well-documented. As the decline of this species in the northern part of its range is ongoing, and its extirpation from the state possibly imminent, appropriate habitat should be surveyed to document its persistence (or lack thereof).

Management

Whether in more natural habitats kept open by fire or flooding, or in fields, pastures, and other farmlands, or in suburban yards, parks, and gardens, this species needs a diversity of flowers blooming throughout the growing season. Tussock grasses (or "bunch" grasses) provide nesting sites. Threats such as introduced pathogens or pesticide use must be absent or sufficiently diffuse. Habitat condition should be monitored and management adapted as needed.

Research needs

The basic natural history and conservation needs of the American bumble bee are relatively well known. However, the relative importance of various threats driving the current decline of this species in Massachusetts are not well understood. As a southern species, a warming climate is not a likely threat; however, other effects of climate change on this species are possible and should be studied.

Acknowledgements

Significant contributions to our knowledge of the American bumble bee in Massachusetts have been made by Robert Gegear, Joan Milam, and Michael Veit.

References

Cameron, S.A., J.D. Lozier, J.P. Strange, J.B. Koch, N. Cordes, L.F. Solter, and T.L. Griswold. 2011. Patterns of widespread decline in North American bumble bees. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 108(2): 662-667.

Colla, S.R. 2016. Status, threats and conservation recommendations for wild bumble bees (Bombus spp.) in Ontario, Canada: a review for policymakers and practitioners. Natural Areas Journal 36(4): 412-426.

Grixti, J.C., L.T. Wong, S.A. Cameron, and C. Favret. 2009. Decline of bumble bees (Bombus) in the North American Midwest. Biological Conservation 142(1): 75-84.

Williams, P., S. Colla, and Z. Xie. 2009. Bumblebee vulnerability: common correlates of winners and losers across three continents. Conservation Biology 23(4): 931-940.

Williams, P., R. Thorp, L. Richardson, and S. Colla. 2014. Bumble Bees of North America. Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey. 208 pp.

Contact

| Date published: | March 28, 2025 |

|---|