- Scientific name: Sterna paradisaea

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Special Concern (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Arctic tern (Sterna paradisaea)

The Arctic tern measures 35-43 cm (14-17 in) in length and weighs 107 g (3-4 oz). It has a white body with gray upperparts, paler gray underparts, a black cap, a blood-red bill, and a deeply forked tail. It has a wingspread of 65-90 cm (29-33 in). Its most distinguishing features are its short red legs and its long tail that extends past the end of its folded wings. Juveniles have a short black bill, white forehead, short legs and a sooty-colored area from its eye to the nape of its neck. The Arctic tern has a squeaky, high-pitched call of “kee-kee,” “kip, kip, kip-TEE-ar,” and a short “kee-kahr.”

The Arctic tern is distinguished from the very similar common tern (Sterna hirundo) by its shorter, red legs and bill, longer tail, and grayer underparts. In addition, the Arctic tern’s thinner bill is typically completely blood-red during the breeding season, whereas the common tern’s is orange-red and has a black tip. In comparison to the common tern, the Arctic tern’s voice is higher-pitched.

Life cycle and behavior

Arctic tern seen off the coast of Cape Cod

Phenology. In temperate areas, Arctic terns arrive 3-4 weeks before laying, initially visiting nesting sites only briefly. In Massachusetts, Arctic terns arrive on their breeding grounds in mid-May. Limited data show egg laying dates between May 21 and July 12. Arctic terns depart as soon as the young can fly and the species is rarely seen in Massachusetts after August.

Colony. The Arctic tern nests in colonies ranging from several to tens of thousands of pairs. In Massachusetts, they are found within common tern colonies.

Responses to predators and intruders. The Arctic tern prefers to nest on islands lacking predatory mammals. Eggs and chicks are cryptically colored and hatched eggshells are removed from the nest. Colony-nesting seabirds, such as terns, benefit from group defense. Most predators and intruders to the nesting colony are dived at, pecked, and defecated on.

Pair bond and parental care. Courtship involves aerial flights and carrying and subsequent transfer of a fish, and later, mate feeding. Both parents care for nests and young, but the female has a greater role in incubating the eggs and brooding the young, while the male provides more food, which the adult carries in its bill to young. In most years during 2007-2020, a single Arctic tern male mated with a common tern female at Penikese Island, Massachusetts, producing hybrid young; their pair bond lasted at least 14 years.

Nests. Nests are depressions or “scrapes” in the substrate that may be lined with vegetation, stones, or other materials deposited throughout incubation.

Eggs. Clutches generally contain 1-2 (sometimes 3) sub-elliptical, brownish-green eggs, which are virtually indistinguishable from common tern eggs. Incubation lasts approximately 21-23 days.

Young. Chicks are semi-precocial. Young fledge 21 to 24 days after hatching.

Diet and foraging: The Arctic tern has a broad diet. It feeds on small fish (including herring, hake, sand lance, capelin), insects (including ants, craneflies, chironomids, beetles), small crustaceans (including amphipods, shrimps, krill), marine worms, mollusks, and occasionally berries. It feeds by plunge-diving, diving-to-surface, contact-dipping, or taking prey on the wing.

Demography and survival: Most individuals begin breeding at 3 to 4 years of age. Just one brood per season is raised and Arctic terns do not renest after losing chicks. Annual survival of adults has been estimated at 82-87%. The oldest documented wild Arctic tern is a Maine-hatched individual encountered at age 33 years and 11 months.

Population status

The Arctic tern is listed as a species of special concern in Massachusetts. Records of this species have been inconsistent in the past due to the difficulty of identifying this bird and distinguishing it from the common tern. However, it is generally believed that in Massachusetts, the Arctic tern was very rare in the late 1800s and required more time to recover from the deleterious effects of the millinery trade than the common or least terns. On Cape Cod in 1937 and 1938, 60 pairs of Arctic terns were reported; in 1946 and 1947, 280 pairs were found; and between 1968 and 1972, 110 pairs were reported. These numbers may not reflect an entirely accurate picture of the Arctic tern population in Massachusetts due to the reasons cited above.

Since the apparent peak in population numbers during the late 1940s, the Arctic tern has experienced a noticeable decline (Figure 1) of unknown cause, despite legal protections enacted in the early 1900s that prohibited plume-taking. As Massachusetts is at the southern edge of the species’ breeding range, it is possible that the Arctic tern will always occur in limited numbers in the state. Warming oceans may be causing its range to retract further northward. Since 2011, 0 to 1 pairs have nested in Massachusetts, and sometimes a single individual paired with a common tern.

Distribution and abundance

Outside of the migratory period, the Arctic tern’s global distribution is restricted to a narrow latitudinal range within about 10° of the polar edge of continental landmasses. The Arctic tern has a circumpolar breeding range. During summer in North America, it occurs as far north as there is open water: from northern Alaska and Ellesmere Island, east to British Columbia, northern Manitoba, Quebec, Newfoundland and Labrador, and south along the coast of Maine to Massachusetts (41◦N), the southern edge of its breeding range. After breeding, Arctic terns from Greenland and Iceland migrate to a productive ocean region between 41-53° N and 27-41° W where they remain for about 3 weeks. After this stopover period, they continue southeast, with birds diverging to follow either a route parallel to the west African coast or the east coast of Brazil before arriving at the Southern Ocean.

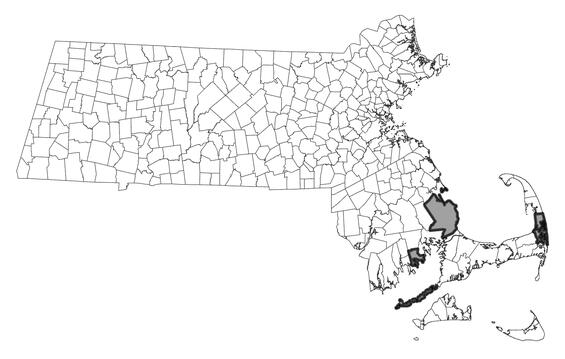

Distribution in Massachusetts. 1999-2024. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

In Massachusetts, the Arctic tern nests on sandy, gravelly, and cobbly areas on islands and barrier spits with scattered vegetation, and occasionally on mainland shores. When nesting, it forages primarily within 20 km (12 mi) of the colony, but up to about 50 km (31 mi). In the non-breeding season, Arctic terns are found near the outer edge of Antarctic pack-ice and nearshore icebergs. In ocean environments, the Arctic tern forages singly or in flocks along shorelines, bays, tidal flats, shoals, ice edges, tidal rips, ocean fronts, upwellings, and over predatory fish that drive prey to the surface.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Arctic tern (Sterna paradisaea)

Threats

Habitat loss: Nesting habitat is threatened by overwash and erosion of low-lying areas, rising sea levels, and increasing frequency and intensity of storms due to climate change. Proliferation of invasive vegetation degrades nesting habitat. Gulls displace Arctics from nesting sites.

Predators. A variety of avian and mammalian predators have large impacts on nesting Arctic terns, including falcons, owls, corvids, gulls, foxes, mink, and rats.

Climate change: In addition to climate-induced habitat loss from rising sea levels and storms, warming oceans may result in changes in prey distribution, abundance, and/or phenology. The rapid melting of polar ice will surely impact this species, which is associated with ice edges. Vegetation in the Arctic tern’s restricted latitudinal range is expected to change dramatically as the climate changes.

Wind farms: The construction and operation of offshore wind turbines, which are poised to proliferate in the Northeast, may cause changes to prey availability, displacement from foraging habitat, and mortality from collisions.

Disease and biological toxins: To date, diseases have not had a major impact on Arctic terns in the Northeast US. Small numbers of Arctics have been killed by avian cholera and paralytic shellfish poisoning associated with “red tide” events. However, diseases, including emerging ones such as HPAI, potentially could have large impacts in the future.

Plastic: Plastic trash in the environment poses a threat as it can be mistaken as food by seabirds and shorebirds and ingested or cause entanglement. Ingested plastics, common for seabirds, can block digestive tracts, cause internal injuries, disrupt the endocrine system, and lead to death. Entanglement from fishing gear and other string-like plastics can cause mortality by strangulation and impairing movements.

Conservation

The Arctic tern is a conservation-dependent species. Management techniques at nesting sites include signage, restricting human/dog access, vegetation management, gull displacement or removal, predator control, and habitat restoration. Arctic terns in Massachusetts continue to be threatened by predators, displacement by gulls, and erosion; however, the biggest threat for our range-edge population may be climate change. Avoid or recycle single-use plastics and promote and participate in beach cleanup efforts.

References

Bird Banding Laboratory. North American Bird Banding Program Longevity Records. Version 2023.2. Eastern Ecological Science Center. US Geological Survey. Laurel, MD.

Egevang, C., I. J. Stenhouse, R. A. Phillips, A. Petersen, J. W. Fox, and J. R. D. Silk. 2010. Tracking of Arctic terns Sterna paradisaea reveals longest animal migration. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences: 107 (5) 2078-2081.

Hatch, J. J., M. Gochfeld, J. Burger, and E. Garcia (2020). Arctic tern (Sterna paradisaea), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Mostello, C. S., D. LaFlamme, and P. Szczys. 2016. Common tern Sterna hirundo and Arctic tern S. paradisaea hybridization produces fertile offspring. Seabird 29: 39-65.

Veit, R. R., and W. R. Petersen (1993). The Birds of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Audubon Society, Lincoln, MA, USA.

Veit, R. R. and C. S. Mostello. 2006. Latest Occurrence of Arctic tern for Massachusetts. Bird Observer 34 (1): 38-39.

Contact

| Date published: | April 24, 2025 |

|---|