Overview

The Massachusetts Department of Early Education and Care (EEC) was formed on July 1, 2005 through Chapter 205 of the Acts of 2004. This legislation merged the early childhood care offices of the Office of Childcare Services at the Department of Children and Family Services and the Early Learning Services Office at the Department of Elementary and Secondary Education. EEC responsibilities include licensing childcare programs, providing financial assistance for childcare services to families with low incomes, providing parenting support to families, and providing professional development opportunities to employees in the field of early education and care. According to EEC’s website, its mission is “to support the healthy growth and development of all children by providing high quality programs and resources for families and communities.”

EEC licenses approximately 9,000 childcare-related programs that support an average of 55,000 children daily. EEC licenses group, school-age, and Family Child Care (FCC) programs; FCC assistants; residential programs for children; and adoption/foster care placement agencies. Licensing of all childcare programs includes EEC annually visiting programs and conducting background record checks on childcare staff members.

EEC has five regional offices across Massachusetts, located at 1441 Main Street in Springfield (western region), 324R Clark Street in Worcester (central region), 360 Merrimack Street in Lawrence (northeast region), 100 Myles Standish Boulevard in Taunton (southeast region), and 100 Hancock Street in Quincy (Boston metropolitan region). EEC’s main office is located at 50 Milk Street in Boston.

As of March 3, 2023, EEC had 246 employees. EEC had state appropriations of $852.27 million in fiscal year 2021, $819.08 million in fiscal year 2022, and $1.18 billion in fiscal year 2023.

Licensing Education Analytical Database

The Licensing Education Analytical Database (LEAD) is the platform EEC staff members and programs use to document childcare licensing and investigation actions. The database includes information about each program’s licensing visits, monitoring visits, complaints, background record checks, and investigation records. EEC also uses LEAD as a scheduling tool for EEC’s Licensing and Investigations Units.

Residential Program Licensing and Background Record Checks

Residential programs offer group care and facility living for children. EEC licenses two types of residential programs—group care programs and temporary shelters. During the audit period, there were 364 licensed residential programs (333 group care programs and 31 temporary shelters). Group care programs provide care for children under the age of 18 on a 24-hour residential basis for periods longer than 45 days. These programs provide services intended to help residents under 18 years of age transition into independent living programs, when that transition is appropriate, and provide treatment for residents with mental health issues, behavioral issues, developmental disorders, or previous traumas. Temporary shelters provide care for residents under the age of 18 for periods of no more than 45 days in an EEC facility nor more than 90 days in Department of Youth Services facilities that are licensed by EEC. A parent, child, placement agency, law enforcement agency, or court order can request placement in a temporary shelter.

To ensure that EEC complies with its Differential Licensing Residential Handbook, EEC’s licensors must visit each licensed facility on an annual basis. Licensors are responsible for all licensing activities that include licensing and renewals, conducting monitoring site visits, and investigating complaints.

One of the key checks EEC performs during this annual visit is the verification that all candidates for a residential licensure program for employment, internships, or regular volunteer positions who might have supervised or unsupervised access to children in their care received background record checks. EEC’s staff members conduct a background record check in accordance with Section 14.05 of Title 606 of the Code of Massachusetts Regulations (CMR), which includes the following components, or checks:

- a Massachusetts Criminal Offender Record Information check;

- a Department of Children and Families (DCF) check;1

- a Sex Offender Registry Information check; and

- fingerprint-based checks of state and national criminal history databases.2

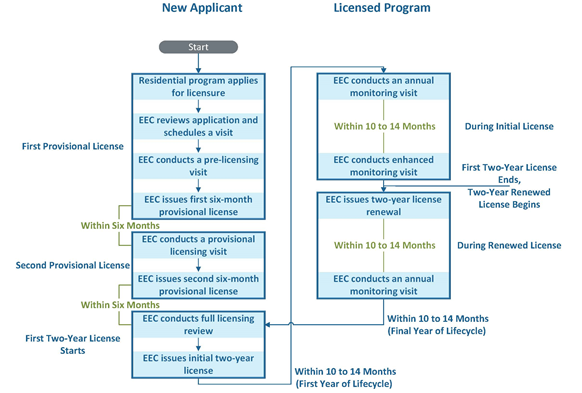

The Differential Licensing Residential Handbook defines the process for those seeking residential program licenses. See the chart below.

Residential Program Licensing Lifecycle

A new residential program’s licensing process begins when it submits its license application materials and application fee to EEC. An EEC licensor then reviews the license application materials and schedules a pre-licensing visit to review all the licensing regulations. A licensor documents and tracks these in LEAD. If the licensor finds the program compliant with the regulations contained within the Differential Licensing Residential Handbook during a pre-licensing visit, EEC grants the program a six-month provisional license. Before the first provisional license expires, EEC conducts a provisional licensing visit. If a licensor finds the program compliant with the handbook during the provisional licensing visit, EEC grants a second six-month provisional license. Before the second provisional license expires, the program submits an application for a two-year license. After reviewing this application, a licensor conducts a full licensing review visit. If the program is compliant with the handbook during the full licensing review visit, EEC issues a two-year license.

For currently licensed programs, the EEC licensing process begins with a monitoring visit, which EEC conducts 10 to 14 months after it issues a two-year license. The next visit EEC conducts is an enhanced monitoring visit within 8 to 12 months of the monitoring visit. If the program is compliant with the Differential Licensing Residential Handbook during the enhanced monitoring visit, EEC issues a two-year license renewal for the program.3 EEC then conducts another monitoring visit within 10 to 14 months of issuing a two-year license renewal. At the expiration of the two-year license renewal, EEC performs a new full licensing review visit and issues a new two-year license to a program, if EEC finds the program to be compliant with the handbook during this visit. After the completion of this licensing review and issuance of a two-year license, the license and visit process for a licensed residential program begins again with a monitoring visit. See Appendix A for an explanation of the licensing activities performed during site visits.

FCC Licensing and Background Record Checks

EEC licenses FCC programs to provide care within FCC program homes, which are the homes owned or occupied by childcare providers. EEC licenses FCC programs for up to 6, 8, or 10 children. During the audit period, there were more than 5,700 licensed FCC programs. EEC’s licensors verify licensed program compliance with state and federal requirements. EEC’s licensors verify compliance by visiting licensed facilities on an annual basis. FCC programs submit the names of all licensees, assistants, and household members aged 15 years or older for background record checks, as required by Section 98.43(b) of Title 45 of the Code of Federal Regulations and 606 CMR 14.05. EEC staff members conduct these background record checks, which include the following eight components:

- a Massachusetts Criminal Offender Record Information check;

- a DCF check;

- a Massachusetts Sex Offender Registry Information check;

- national fingerprint-based checks of state and national criminal history databases;

- a National Crime Information Center National Sex Offender Registry check;

- an interstate criminal history check in any state other than Massachusetts that the applicant lived in within the last five years;

- an Interstate Sex Offender Registry check in any state other than Massachusetts that the applicant lived in within the last five years; and

- an Interstate child abuse and neglect registry check in any state other than Massachusetts that the applicant lived in within the last five years.

Before September 2022, EEC background record checks for FCC members did not include the National Sex Offender Registry or three interstate checks, as EEC was operating under a waiver from the federal Office of Child Care.

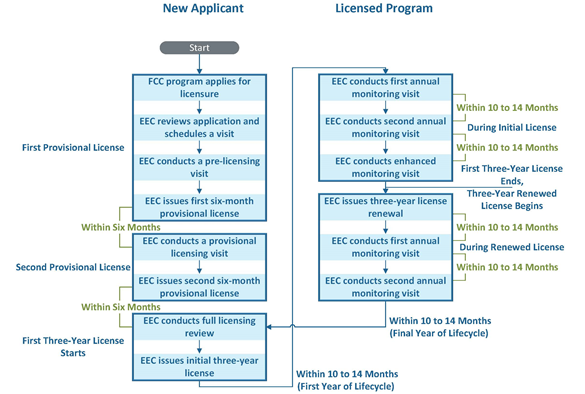

The Differential Licensing Residential Handbook defines the licensing lifecycle for FCC. See the chart below.

FCC Program Licensing Lifecycle

A new FCC program’s licensing process begins when it submits its license application materials and application fee to EEC. An EEC licensor then reviews the license application materials and schedules a pre-licensing visit to review all the licensing regulations. A licensor documents and tracks these in LEAD. If a licensor finds the program compliant with the Differential Licensing Residential Handbook during the pre-licensing visit, EEC grants a six-month provisional license. Before the six-month provisional license expires, a licensor conducts a provisional licensing visit. If the licensor finds the program compliant with the handbook during the provisional licensing visit, EEC grants a second six-month provisional license. Before the second six-month provisional license expires, the licensor conducts a full licensing review visit. If the program is compliant with the handbook during the full licensing review visit, EEC issues a three-year license, which can be renewed for another three years, and the program enters the six-year licensed program lifecycle.

For FCC programs that already have a three-year license, the first visit after the issuance of a three-year license is a monitoring visit, which EEC conducts within 10 to 14 months of the full licensing review visit. EEC conducts another monitoring visit within 10 to 14 months of the first monitoring visit of this cycle. EEC then conducts an enhanced monitoring visit within 10 to 14 months of its second monitoring visit. If the program is compliant with the Differential Licensing Residential Handbook during enhanced monitoring visit, EEC issues a three-year license renewal for the program. EEC conducts monitoring visit within 10 to 14 months of the enhanced monitoring visit. At the three-year renewal license’s expiration, EEC performs a new full licensing review visit and issues a new three-year license if the program is found compliant with the handbook during this visit. After an FCC completes the full licensing review process and is issued a three-year license, the next part of the six-year process is a monitoring visit. See Appendix A for an explanation of the licensing activities performed during site visits.

Investigation of 51A Reports Received from DCF

EEC is required by Section 9 of Chapter 15D of the General Laws to investigate 51A Reports it receives from DCF. A 51A Report is an allegation of abuse or neglect of children that DCF receives from mandated reporters4 and the public. All 51A Reports are initially submitted to DCF in accordance with Section 51A of Chapter 119 of the General Laws. EEC and DCF have a memorandum of understanding through which DCF agrees to share information regarding reports received involving EEC-licensed programs. After DCF receives a 51A Report, DCF performs a screening process to determine whether further investigation is necessary. The report is screened out if DCF determines that it requires no further investigation. If DCF determines that the allegations in the 51A Report meet DCF’s criteria for suspected child abuse and/or neglect, DCF will screen in5 the 51A Report and will begin its investigation. DCF notifies EEC of its decision within two business days of DCF receiving the report. Currently, EEC Investigations Unit managers receive daily emails with 51A Reports from DCF. The investigations managers at EEC who receive the 51A Reports from DCF determine whether the report involves a licensed program.6 The EEC regional office in the jurisdiction in which the 51A Report incident occurred assigns a risk level based on the allegations contained within the 51A Report, and then assign a licensor or investigator7 to investigate. The assigned licensor or investigator conducts an investigation to determine whether the licensed program is out of compliance with any EEC policies.

A report of abuse or neglect can be investigated by either an EEC licensor or investigator. However, EEC policy requires that all reports that are identified as high-risk be investigated by an EEC investigator, who, according to EEC, is required to have more leadership or supervisory experience and is more qualified to conduct such high-risk investigations. In its Internal Policy Handbook for EEC Childcare Operations Staff, EEC defines a high-risk report as a report that involves at least one of the following:

- Death of a child.

- Allegation of abuse or neglect against a child.

- Screened in 51A. . . .

- Major injury to a child with regulatory concerns.

- Domestic, family, or third-party violence that is reported to have occurred during program operation hours and witnessed by childcare children, as determined following consultation with the Investigations Supervisor

Unlicensed Care Complaints

EEC receives unlicensed care complaints from concerned citizens who believe a person who does not have an EEC license is providing childcare to children who are not relatives of the care provider. Citizens report their concerns to EEC through EEC’s online unlicensed care complaint form, telephone calls, email, conventional mail, and in person at one of its regional offices. EEC follows processes that are documented in its investigation policy to investigate reports and to provide unlicensed care programs an opportunity to become licensed if they meet health and safety requirements. (See Appendix B for these processes.) If EEC finds a report to be accurate and a person is providing unlicensed childcare to children who are not relatives, EEC can either work with the person to become licensed or file a cease and desist order to the person to cease childcare services.

EEC policy requires that unlicensed care complaints categorized as high-risk be investigated by EEC investigators. In its Internal Policy Handbook for EEC Childcare Operations Staff, EEC defines a high-risk unlicensed care complaint as containing allegations that children are at immediate risk of harm that involve the following:

- Death of a child while in care or may have occurred as a result of a condition/incident that happened while in care.

- Sexual abuse of a child by someone who works, lives in, or visits the program.

- Physical abuse resulting in a serious injury requiring medical attention.

- Neglect of a child resulting in a serious injury requiring medical attention.

- Any abuse or neglect of a child coupled with an open criminal case (open with law enforcement).

- Any criminal activity within the licensed program being investigated by law enforcement.

- Domestic, family, or third-party violence that is reported to have occurred during program operation hours and witnessed by childcare children, as determined following consultation with the Investigations Supervisor.

- Substance abuse by an educator or someone who works, lives in, or visits the program.

- Presence, use, or distribution of illegal drugs while children are in care.

Child Trafficking and Sexual Exploitation Training

To address human trafficking in the Commonwealth, the Massachusetts Interagency Human Trafficking Policy Task Force published a report in 2013 highlighting training and policies for educators across Massachusetts as an important component to prevention and detection of human trafficking.

Currently, the federal Preventing Sex Trafficking and Strengthening Families Act has a funding requirement (under Title IV of the act) that states must screen any child who has gone missing or run away from foster care for possible sexual exploitation and human trafficking when they are found or return to foster care. The US Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Inspector General (HHS OIG) selected Massachusetts for review in a 2022 report8 as one of five states with the highest number of runaway children reported in the country. HHS OIG outlined in its report that between July 2018 and June 2019, 949 children in the Massachusetts foster care were reported missing and later found or returned to foster care. HHS OIG reviewed 88 of the 949 cases for evidence of screening and found that, in 82% of cases in Massachusetts, caseworkers did not conduct the required screening when a child was found or returned. Presently, DCF is responsible for overseeing and developing policies for Title IV funding. In order to ensure state compliance with the Title IV funding requirement, DCF established its Policy Regarding Missing or Absent Children in Department Care or Custody, which requires that social workers screen children when they are found or returned to foster care after they go missing. The Massachusetts Interagency Human Trafficking Policy Task Force also recommends that educators receive training to screen for victims of human trafficking.

EEC Essentials Training for Funded Programs

Funded programs are children programs that are not subject to licensure by EEC but have either a contract with EEC or a voucher agreement with a local Child Care Resource and Referral Agency, to provide subsidized childcare for familes who have low incomes or are otherwise at risk. During the audit period, there were 172 active funded programs. Funded programs provide services primarily limited to kindergarten, nursery, or preschool children and the setting of a funded program can be a public, private, religious, or parochial school, or a government, tribal, or military childcare program.

The Child Care Development Fund requires that a program meet certain requirements to be eligible to receive federal funds. Before entering into a voucher agreement with a Child Care Resource and Referral Agency, a program must receive a certificate of eligibility from EEC, which lets the Child Care Resource and Referral Agency know that EEC has reviewed a program and that the program has met all the requirements to provide care for children whose families qualify for subsidy. EEC renews this certificate of eligibility every two years. EEC verifies a program’s continued compliance with the requirements by conducting annual monitoring visits to funded programs. EEC records its results in LEAD.

One requirement for funded programs is that all staff members working with children must complete EEC Essentials training hosted by EEC, which are available online. EEC verifies a program’s compliance with this requirement during its monitoring visits. EEC Essentials training includes the following 12 training modules, all of which take approximately 12 hours in total to complete:

| Child Abuse and Neglect | Infectious Diseases and Immunizations |

| Emergency Response Planning | Introduction to Child Development |

| First Aid and Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation Overview | Medication Administration |

| Food-Related Risk and Response | Physical Premises Safety |

| Hazardous Materials | Shaken Baby Syndrome |

| Infant Safe Sleeping Practices | Transporting Children |

Language Access Plans

The Massachusetts Office of Access and Opportunity requires that all state agencies in the executive branch that provide services, programs, or activities that are normally provided in English to establish a language access plan. The Office of Access and Opportunity further requires that agencies update their language access plans every two years.

The Massachusetts Commission on LGBTQ Youth

According to the Massachusetts Commission on LGBTQ Youth’s website, the commission was founded in 1992 by Governor William Weld to address the high suicide risk among LGBTQ youth. In 2006, the commission became an independent state agency in accordance with Section 67 of Chapter 3 of the General Laws and works with other state agencies to achieve its goals. The commission has been making recommendations to EEC to improve the care of LGBTQ in EEC’s care since fiscal year 2018 and in each annual report thereafter.

| Date published: | November 25, 2024 |

|---|