- Scientific name: Tyto alba

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Special Concern (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

American barn owl (Tyto alba)

The American barn owl, also known as the monkey-faced owl, is quite different in appearance from other owls owing to its distinctive heart-shaped face and dark eyes. Its large head lacks feathered ear tufts, and its plumage is buff or light tan in color with brown specks on the upper portions. Females have a buff-colored breast lightly spotted with black, and males have a white breast with fewer spots. The wings are long and rounded, and the tail is short. They have long, sparsely feathered legs and powerful feet tipped with needle-sharp talons. This medium-sized owl is approximately 33-36 cm (13-14 in) tall, with a wingspan of 97-112 cm (38-44 in). Females are generally larger than males, weighing an average of 570 g (20 oz) to a male's 455 g (16 oz).

The barred owl (Strix varia) and the northern saw-whet owl (Aegolius acadicus), both present in Massachusetts, similarly lack feathered ear tufts. Four other owl species present in Massachusetts have prominent ear tufts and these are: great horned owl (Bubo virginianus), Eastern screech owl (Otus asio), long-eared owl (Asio otus), and short-eared owl (Asio flammeus).

Life cycle and behavior

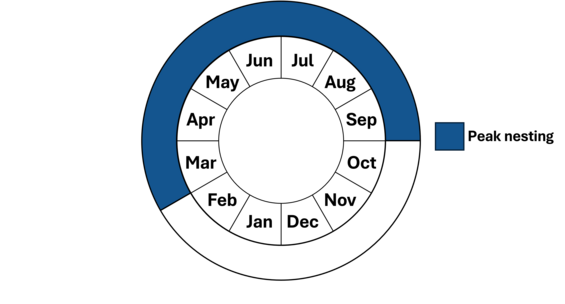

Phenology in Massachusetts. This is a simplification of the annual life cycle. Timing exhibited by individuals in a population varies, so adjacent life stages generally overlap each other at their starts and ends.

Barn owls are nocturnal and secretive, yet they are also extremely curious and investigate holes and crevices. The barn owl is, for the most part, monogamous and mates for life. Its short life span averages about two years; therefore, most breed only once or twice during their lifetime, and breeding usually begins at one year of age. Mating pairs may produce more than one brood in a year and eggs have been found at active nests in Massachusetts in every month of the year. Courting behavior, however, usually begins by March, initiated by the male with display flights. A chase follows, where the male pursues the female. The male also engages in "moth flights" in which he hovers with his feet dangling in front of the perched female for several seconds. Both sexes solicit copulation by crouching in front of each other. The female may encourage the male by swaying and vibrating her wings. Egg laying begins about one month later with 3-11 dull white eggs laid. The female begins incubating upon laying the first egg and continues for 29-34 days. The male is the primary hunter, yet only the female feeds the young. After about two weeks, the young can swallow prey whole, and at this time the female starts to assist in hunting. The owlets attempt their first flight about 50-55 days after hatching; fledging occurs at about 60 days. Fledglings return to the nest cavity to roost for several weeks and may roost in the vicinity for 7-8 weeks after flying. The barn owl's nesting success is related to and closely dependent upon vole populations. When vole numbers are low, perhaps due to a dry spring, the owls produce fewer eggs and, unable to provide enough food, fledge fewer young. Older siblings will often cannibalize younger nest mates when food is limited. In cases of extreme lack of food, adults will abandon their young.

Unlike other owls, barn owls do not hoot. Instead, both sexes utter a short harsh note when returning to the nest site. Their alarm call is a loud, piercing screech. Barn owls eat a variety of prey, mostly rodents and small mammals, and have an overwhelming preference for meadow voles (Microtus pennsylvanicus). Occasionally, they will eat other birds. Barn owls hunt mainly at night, starting an hour after sunset and ending an hour before sunrise. They detect prey with their excellent vision and hearing and are capable of capturing prey in total darkness using their hearing alone. Most prey is swallowed whole.

Population status

The barn owl is listed as a species of special concern in Massachusetts. A special concern species occurs in small numbers, has specialized habitat requirements and a restricted range, or has been found to be declining in numbers to the extent that its existence may be threatened. The fact that these birds are generally year-round residents and will succumb to cold and starvation rather than migrate has contributed to their tenuous status in Massachusetts. Changes in agricultural practices are the most likely cause of population declines in the past 20 years. These changes have meant decreased availability of open farm structures for nesting and roosting, and a decline in agricultural lands that support high densities of small mammals. Better grain storage and fewer grasslands constrict rodent food sources, resulting in fewer prey items.

Distribution and abundance

The barn owl prefers climates with mild winters and occurs throughout much of North America and south through Central America, and South America. They breed in North America south of a line extending from southwestern British Columbia through southern Idaho, southern Wisconsin, southern Ontario, and southern Vermont.

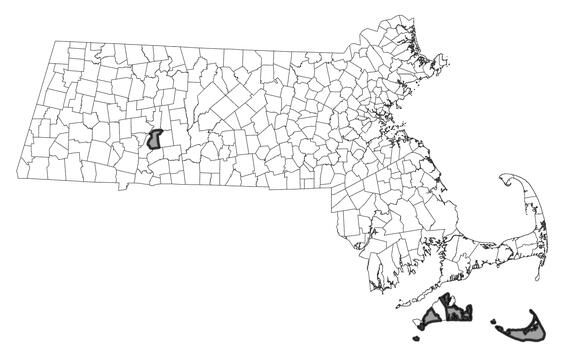

Records of barn owls in Massachusetts date back to the late 1800s, and this species is found mainly along the coastal plain from Newburyport south to Cape Cod and the surrounding islands. It also turns up occasionally in the Connecticut and Housatonic River Valleys. However, in western Massachusetts, the last known nesting attempt was in 1981. The owl appears to be extremely rare or nonexistent throughout much of the state, but it is difficult to detect because of its secretive nature. Therefore, our knowledge of its current status is somewhat speculative.

Distribution in Massachusetts. 1999-2024. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

American barn owls require grassy habitats for foraging, such as fresh- and salt-water marshes and agricultural fields. They rarely occur apart from populations of the meadow vole (Microtus pennsylvanicus), a primary food source, and avoid areas of deep snow and prolonged cold, which can preclude successful foraging. The barn owl is resourceful in making use of such nesting sites as hollow trees, cavities in cliffs or riverbanks, and artificial structures such as nest boxes, old barns, and bridges.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

American barn owl (Tyto furcata)

Threats

Common threats to the American barn owl include predation, starvation due to severe winter or drought, collisions with vehicles and electrocution from power lines. Also, as inhabitants of farmsteads, barn owls are potentially exposed to a variety of insecticides and rodenticides. Humans have primarily affected barn owls through habitat destruction, illegal shooting, and nest disturbance.

Rodenticides (e.g., Second Generation Anticoagulant Rodenticides - SGARs) move up food chains and pose a threat to raptors when they consume prey that have ingested these chemicals. As a result, SGARs have been found in a high percentage of raptors that have been tested for them in Massachusetts, and it is well documented that they can kill individual raptors. However, their population-level impacts on raptors remain largely unknown.

Conservation

Conserving and maintaining open habitat suitable for nesting American barn owls is important for the conservation of the species in the state. These efforts should be directed in the southeast portion of the state that continues to host sizeable populations of the species and similar efforts along the Connecticut River Valley may promote the return of barn owls to this region of Massachusetts. To promote nesting in areas with known barn owl populations, nest boxes can be deployed in suitable habitat. Limiting the use of rodenticides in these areas also will promote barn owl conservation.

Conduct research to better understand the impacts of highly toxic rodenticides (e.g., SGARs) to raptor populations. Promote an integrated pest management approach that emphasizes the use of alternative pest control measures whenever possible to reduce negative impacts to wildlife. Coordinate with other state agencies to improve tracking and reporting of rodenticides found in wildlife and develop outreach materials for the public.

References

Marti, C. D., A. F. Poole, L. R. Bevier, M.D. Bruce, D. A. Christie, G. M. Kirwan, J. S. Marks, and P. Pyle (2024). American Barn Owl (Tyto furcata), version 1.1. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, B. K. Keeney, and M. G. Smith, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Rosenburg, C. “Barn Owl (Tyto alba).” 1992. Migratory Nongame Birds of Management Concern in the Northeast (K.J. Schneider and D.M. Pence, eds.). U.S. Department of the Interior, Fish and Wildlife Service, Newton Corner, MA, 253-279.

Terres, J.K. The Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds. New York: Wings Books, 1991.

Contact

| Date published: | April 24, 2025 |

|---|