- Scientific name: Carex buxbaumii Wahlenb.

Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

Description

Buxbaum’s sedge in fruit

Buxbaum's sedge is a grass-like plant in the genus Carex, the most species-rich genus in Massachusetts with 180 taxa, and is abundant throughout the northeastern states (Bennett 1996, Cullina et al. 2011). Technical skills and a detailed dichotomous key are needed for proper identification with this group of plants.

Buxbaum's sedge is rhizomatous and forms a turf with stems sometimes loosely clustered together and at times long-spreading and arising singly. The leaves up to 4 mm (5/32 in) wide.

Height: Buxbaum’s sedge can grow up to 50 cm (19.7 in). Flowering spikes are erect or ascending, on short peduncles. Spikes are up to 25 mm (1 in) in length and up to 10 mm (0.4 in) wide with 2 to 4 lateral pistillate spikes and a terminal spike that is gynecandrous (the staminate flowers are below the pistillate flowers). In some cases, there are a few staminate flowers also at the tip of this terminal spike. Pistillate scales are typically dark brown, though variously described as anywhere from brown, to dark purple, to black. These scales are lanceolate, about as long as the perigynia (the green covering of the achene), with a distinctive and prominent midvein that is lighter than body. The apex is acute or acuminate, and sometimes with a needle-like tip. The perigynia are ascending, smooth, light green to whitish green, elliptic, and to 4 mm (0.16 in) long. The achenes nearly fill the body of perigynia.

Buxbaum’s sedge full seed head structure 4 cm (1.6 in) in length with two lateral pistillate spikes and one terminal spike with staminate flower scales subtending pistillate seed structures each with a subtending dark brown scale with a light colored central line

Ripening seed head showing dark brown scales of staminate flowers subtending lime-green colored perigynia and the associated dark brown pistillate scales with distinct center line and pointed tips.

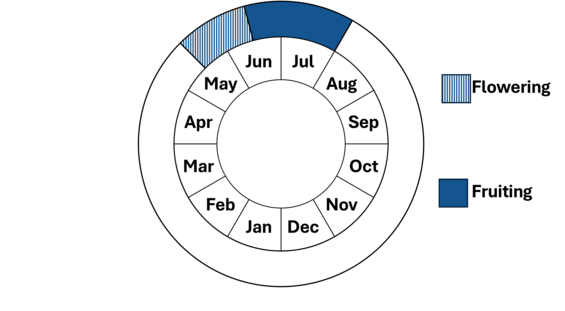

Life cycle and behavior

Buxbaum’s sedge is a perennial and generally flowers every year. It is wind pollinated.

Carex buxbaumii flowers can appear in the last week of May and begin setting fruit by June 6, retaining fruit for the remainer of June and July.

Population status

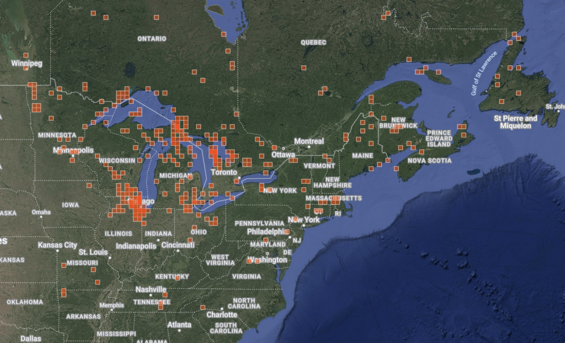

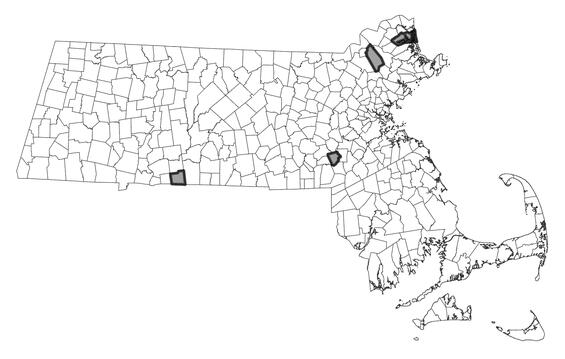

Buxbaum’s sedge has been tracked by MassWildlife’s Natural Heritage Endangered Species Program (NHESP) as a watch-list species since 1988 and has 7 records since that time. As of 17 February 2025, iNaturalist had 8 research-grade observations for this species scattered throughout the state north of Bristol and Plymouth counties, though 3 of these are from the same location. When in fruit, the species is not easily overlooked, and has clear distinctive features, so we can assume that most populations are likely to have already been discovered.

Map of research-grade observations of Carex buxaumii in eastern North America screen-captured from iNaturalist.org on 15 February 2025.

Distribution and abundance

Buxbaum's sedge is a widespread species across northern latitudes in North America and has a circumboreal distribution worldwide, occurring in Greenland and across Eurasia as well (POWO 2025). In New England, it is ranked an S1-Endangered or extremely rare species in Vermont, New Hampshire, Connecticut and Rhode Island (Native Plant Trust 2025). In Maine, it is considered uncommon and occurs throughout, except in the south (Arsenault 2013). In Massachusetts, it is ranked an “S2?” which means data are limited and have some uncertainty, but the plant is considered rare and likely vulnerable. The plant has been found in all counties north of the Cape Cod Canal except Bristol, Franklin, and Suffolk counties (Bertin et al. 2020, Cullina et al. 2011).

Distribution in Massachusetts

2000-2025

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database

Habitat

Buxbaum’s sedge is an obligate wetland species that occurs typically in full sun in wet meadows that are often mowed or harvested for hay on a once-per-year basis. Several populations are on powerline rights-of-way which are kept free of trees. It is a known calciphile, so its occurrence typically indicates calcium-rich moisture in the soil. Associated native species include shrubby cinquefoil, royal fern, marsh fern, tussock sedge, sallow sedge, broom sedge, cattail, marsh speedwell, and the invasive exotic glossy buckthorn and sweet vernal grass.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Buxbaum’s sedge is threatened by natural succession when wet meadows become overgrown with shrubs and trees. Wet meadows are often threatened by problematic invasive species such as glossy buckthorn (Frangula alnus), purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), and giant reed grass(Phragmites australis) which can all grow quickly and thickly, shading and crowding out the sedges. Disruption of the natural hydrologic regime is also a threat. Wet meadows tend to be groundwater fed. All Terrain Vehicle use and tractors used to mow this habitat when it is too wet can cause deep rutting and create local disturbance that affects hydrology that can provide areas where invasive plants can seed in. This being a species of more northerly distribution, climate warming is a potential threat. The past 130 years have seen a warming of 1.4 ⁰C (2.5 ⁰F) in the Northeast United States (Staudinger et al. 2024). Northern species can be expected to move much further north in an attempt to occupy a habitat within their evolved climate envelope, shrink in distribution, or become extirpated.

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

Given these are hardy perennial species, monitoring could be done on a five-year cycle in June with estimates of plant vigor and seed production and including a threat assessment. Special emphasis should be made to target known sites that are 20 or more years overdue for survey and monitoring. Monitors need to allocate time to contact landowners or land managers to alert them to the populations and advise them on best management practices. This time allocation is often overlooked which presents a challenge to rare plant conservation.

Management

Annually hayed wet meadows were once common in the state in the two-centuries prior to tractors being introduced in the 1920s. Salt marshes were hayed even three centuries prior to 1943 in Massachusetts (Harris 2014). In these modern times when considering ecological history, we may to be reminded that largely until 1940, agriculture was entirely dependent on horses. Horses needed fodder, and harvest from wild wet meadows, including Buxbaum’s sedge, provided the perfect winter food supply. Horses were sometimes equipped with special shoes to be able to harvest hay from wet meadows, though often by late summer the inland meadows were dry enough to be easily harvested. This process produced ideal habitat for a variety of rare plants and animals. It kept the meadows open and grassy, preventing the incursion of shrubs and trees. But since the disappearance of work horses on farms, and widespread drainage of these meadows, many of the fields have succeeded to shrub or red maple swamps or been converted to crop fields. Mowing meadows is a common practice among land managers including MassWildlife. Mowing, as opposed to haying, does not remove the cut vegetation, leaving in some places a heavy layer of thatch through which herbaceous plants struggle to grow through. Haying removes the cut plant material and is preferred choice for this species and many others. Haying has been reduced in part because there isn’t much demand for late season hay, and secondly the equipment itself has become less common. Mowing former hay meadows is a widespread conservation practice in species-rich European semi-natural grasslands. Once-a-year mowing seems to be the most effective method rather than an interval of every two or three years (Hájková et al. 2022, Milberg et al. 2017). Grazing has also been shown to be beneficial in some circumstances at certain intensity levels with specific livestock (Tälle et al. 2016).

Another important aspect to management of wet meadows is to remove and reduce populations of all invasive species, especially those mentioned in the threat section.In certain situations, prescribed fire is an ideal approach to battling invasives, restoring plant diversity and removing the thatch layer that might result from mowing.

Research needs

As this plant is under-surveyed, more standard information is needed such as identification of associated species, evaluation of habitat needs and threats, and assessments of suitable soil conditions and phenology. Research is needed to determine whether this plant can be grown in a nursery or garden setting for purposes of reintroductions. If habitat degradation accelerates losses of current populations, reintroductions could prove useful to the long-term conservation of this species.

References

Arsenault Matt, Glen H. Mittelhauser, Don Cameron, Alison C. Dibble, Arthur Haines, Sally C. Rooney, and Jill E. Weber. 2013. Sedges of Maine: A Field Guide to Cyperaceae. University of Maine Press, Orono, ME. 712 pp.

Bennett, J. P. 1996. Floristic summary of Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada, second edition. The Botanical Review 62: 203–206.

Bertin, R. I., M. G. Hickler, K. B. Searcy, G. Motzkin, and P. P. Grima. 2020. Vascular Flora of Franklin County, Massachusetts. New England Botanical Club.

Cullina, M., B. Connolly, B. Sorrie, and P. Somers. 2011. The vascular plants of Massachusetts: a county checklist, 1st revision. Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species. Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Westborough, MA.

CNH 2025 Consortium of Northeastern Herbaria web site, www.neherbaria.org, accessed 14 Feb 2025.

Fernald, M. L. 1950. Gray’s Manual of Botany, Eighth (Centennial) Edition—Illustrated. American Book Company, New York.

Gleason, Henry A., and Arthur Cronquist. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada, Second Edition. Bronx, NY: The New York Botanical Garden, 1991.

Haines, Arthur. Flora Novae Angliae. New England Wild Flower Society, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT. 2011.

Hájková, P., V. Horsáková, T. Peterka, Š. Janeček, D. Galvánek, D. Dítě, J. Horník, et al. 2022. Conservation and restoration of Central European fens by mowing: A consensus from 20 years of experimental work. Science of The Total Environment 846: 157293.

Hipp, A. 2008. Field guide to Wisconsin sedges: An introduction to the genus Carex (Cyperaceae). Univ of Wisconsin Press.

iNaturalist. Available from https://www.inaturalist.org. Accessed 14 February 2025

Native Plant Trust. 2025. Go Botany website. https://gobotany.nativeplanttrust.org/ Accessed 2/17/2025

Harris, G. 2014. Gathering Salt Marsh Hay. Historic Ipswich. Website https://historicipswich.org/2014/02/26/salt-marsh-hay/

Milberg, P., M. Tälle, H. Fogelfors, and L. Westerberg. 2017. The biodiversity cost of reducing management intensity in species-rich grasslands: Mowing annually vs. every third year. Basic and Applied Ecology 22: 61–74.

NatureServe. 2025. NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. Accessed: 2/14/2025

POWO (2025). "Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet; https://powo.science.kew.org/ Retrieved 17 February 2025."

Staudinger, M.D., A.V. Karmalkar, K. Terwilliger, K. Burgio, A. Lubeck, H. Higgins, T. Rice, T.L. Morelli, A. D'Amato. 2024. A regional synthesis of climate data to inform the 2025 State Wildlife Action Plans in the Northeast U.S. DOI Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center Cooperator Report. 406 p. https://doi.org/10.21429/t352-9q86

Tälle, M., B. Deák, P. Poschlod, O. Valkó, L. Westerberg, and P. Milberg. 2016. Grazing vs. mowing: A meta-analysis of biodiversity benefits for grassland management. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 222: 200–212.

Contact

| Date published: | March 25, 2025 |

|---|