- Scientific name: Gavia immer

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Special Concern (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Common loon looking in the water.

Loons represent the entire order of Gaviiformes and have no close relatives. The common loon is named appropriately as it is the most common of the loons, and it is also known as the great northern diver. This heavy, goose-sized waterbird varies considerably in size, ranging from 0.7-0.9 m (28-36 in) long with a wingspan of 1.5 m (5 ft). It has a thick, black, pointed and evenly tapered bill, held horizontally. In summer, its head and neck are black, glossed with green, with a broad, white collar of black-and-white lines on the sides of its mid-neck; its back is cross-banded black with white spots. In winter (October to March), its crown, hind neck, and upper parts are grayish to dark brown, its bill is grey, and its throat and under parts are white. The loon's eyes are bright red from a pigment in its retina that filters light and allows the bird to see underwater. Loons have powerful legs and large, webbed feet that are located far back on the body, a feature that aids them in swimming and diving.

Life cycle and behavior

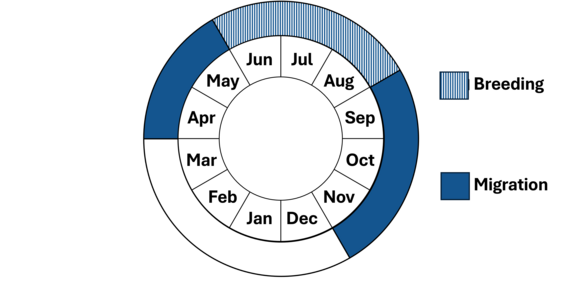

Phenology in Massachusetts. This is a simplification of the annual life cycle. Timing exhibited by individuals in a population varies, so adjacent life stages generally overlap each other at their starts and ends.

As the common loon builds its nest within a few feet of the shoreline, it is very sensitive to disturbance and will sometimes abandon a nest if repeatedly disturbed by motorboats, canoes, or hikers. The loon lays two olive-brown, lightly spotted eggs in a substantial mass of vegetation near the edge of water, usually on an island. Adult loons alternate nest-sitting throughout the 28-day incubation period, and once each chick has hatched, the white egg-membrane and pieces of eggshell are carried off and dropped in deep water by one of the parents. Both parents feed the young for about 6 weeks. At about 11 weeks (by fall), the chicks fledge and migrate to the coast, where they may remain for as long as three years until sexually mature. Common predators of loon eggs and chicks are raccoons, otters, skunks, ravens, and crows.

The call of the common loon is a wild, maniacal laugh along with a mournful wail. It often calls at night, except in winter when it does not call at all. It rides low in the water while swimming, and the fact that it has been found as deep as 200 feet below the water's surface testifies to its expert diving ability. The loon is awkward on land as its legs are set far back on the torso and it has to propel itself forward on its front like a wheelbarrow. Once flying, however, the loon has fast, uninterrupted wing-beats and can reach speeds of over 121 km per hour (75 mph). The common loon migrates in small flocks, mostly to the coast; its northbound migration period on Cape Cod averages from March 30th to June 3rd, southbound from September 1st to November 30th. The loon relies on its excellent eyesight to locate its prey: small fish, crustaceans, shellfish, frogs, aquatic insects, and some water plants. The common loon is a voracious feeder; an adult pair and two chicks can eat 430 kg (948 lb) of fish in one season. Highly territorial, loons behave aggressively when threatened and have been known to kill intruders.

Population status

The common loon is protected under the Federal Migratory Bird Treaty Act and is considered a species of conservation concern in the northern United States and Canada. It is listed as a species of special concern under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act, but because of accelerated management efforts that include monitoring and floating nest rafts, its breeding population in this state has increased from one recorded pair in 1975 to 56 pairs in 2024.

A group of common loons swimming.

Distribution and abundance

The common loon's summer breeding range extends from Alaska to northern California, across Canada to Newfoundland, and south to Wisconsin, Minnesota, northern New York, and Massachusetts. In the Northeast, their breeding range historically extended south to Pennsylvania. It winters along the Pacific and Atlantic coasts as far south as Baja, California, southern Florida, and the Gulf of Mexico. Today, the majority of nesting loons are found in Canada and Alaska.

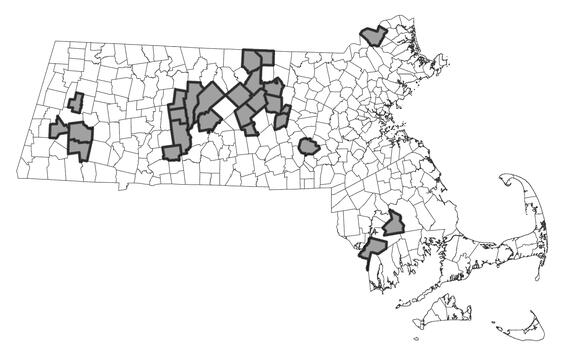

Loons returned to Massachusetts in 1975 after almost a century's absence; they occur statewide as migrants and regularly put down on larger lakes and reservoirs inland, and in summer they nest at the Quabbin and Wachusett Reservoirs and several other waterbodies in central and western Massachusetts. On Cape Cod, common loons are found primarily in salt waters, bays, and estuaries, sometimes many miles offshore.

Distribution in Massachusetts. 1999-2024. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

The common loon is more water-dependent than any other inland bird, only coming to the shoreline in spring to breed and nest. It nests on islands or tall aquatic plants in large, clear northern lakes and ponds, and often returns to the same nesting site for years. In winter, the loon inhabits oceans and bays along the coast from Maine to Texas.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Common loon with chicks swimming in the water.

Lead poisoning, induced by the ingestion of fishing sinkers lost by anglers, appears to be the foremost cause of adult loon mortality on New England lakes. Loons eat minnows being used as bait, and may swallow the hook and sinker, or ingest the sinkers from the lake bottom when swallowing small stones to aid their digestion. When swallowed by the loon, the lead sinker causes the bird to ingest a toxic level of lead that causes the breakdown of its red blood cells and results in kidney failure. Also, acid rain, caused mainly by pollutants from power plants and automobiles, contaminates lakes with mercury, aluminum, and cadmium, metals which reduce loons' reproductive success and render them more susceptible to infectious disease. Acid rain causes some large lakes to become clearer; while these lakes attract loons, acidity reduces the amount of fishes for loons to feed on. Additional threats to loons are pesticides, shoreline development, growing numbers of recreational boaters, and flooding of nests due to human control of water levels in nesting areas. Rising temperatures caused by climate change may also be a threat to loons at the southern portion of their range. Oceanic oil spills can threaten loons on their non-breeding grounds and cause substantial die-off events.

Plastic trash in the environment poses a threat as it can be mistaken as food by seabirds and shorebirds and ingested or cause entanglement. Ingested plastics, common for seabirds, can block digestive tracts, cause internal injuries, disrupt the endocrine system, and lead to death. Entanglement from fishing gear and other string-like plastics can cause mortality by strangulation and impairing movements.

Conservation

Protecting lake shore habitat and islands on waterbodies with nesting loons is critical for promoting breeding success for the species. Reducing the amount of lead fishing equipment in use in freshwater will also benefit the species. Limiting excessive runoff of fertilizers from nearby agriculture will help reduce the number and severity of algal blooms that reduce water clarity and inhibit the birds’ ability to forage. On waterbodies where human recreation occurs (e.g., boating, fishing, swimming), it is important to provide outreach materials to promote loon conservation.

Avoid or recycle single-use plastics and promote and participate in beach cleanup efforts.

References

Mirick, P. 1992. Massachusetts Wildlife, Fall 1992, v. XLII, No. 4.

Blair, R. 1991. Loon Conservation: acidified lakes & habitat selection. Center for Conservation Biology, update v. 5, #2, Fall/Winter 1991.

Paruk, J. D., D. C. Evers, J. W. McIntyre, J. F. Barr, J. Mager, and W. H. Piper (2021). Common Loon (Gavia immer), version 2.0. In Birds of the World (P. G. Rodewald and B. K. Keeney, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.comloo.02

Contact

| Date published: | April 4, 2025 |

|---|