- Scientific name: Sterna hirundo

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Special Concern (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Adult common tern feeds its chick on a rocky shoreline.

The common tern measures 31-35 cm (12-13 in) in length and weighs 110-145 g (3.9-5.1 oz). Breeding adults have light gray upperparts, paler gray underparts, a white rump, a black cap, orange legs and feet, and a black-tipped orange bill. The tail is deeply forked, mostly white, and does not extend past the tips of the folded wings. In non-breeding adults, the forehead, lores, and underparts become white, the bill becomes mostly or entirely black, legs turn a dark reddish-black, and a dark bar becomes evident on lesser wing coverts. Downy hatchlings are dark-spotted buff above and white below with a mostly pink bill and legs. Juveniles are variable: they have a pale forehead, dark brown crown and ear coverts, buff-tipped feathers on grayish upperparts resulting in a scaly appearance, white underparts, pinkish or orangish legs, and a dark bill. The voice has a sharp, “irritable” timber, and includes a keeuri advertising call and kee-arrrr alarm call.

The Arctic tern (Sterna paradisaea) is similar in size, but has a shorter, blood-red bill, very short red legs, much grayer underparts with contrasting white cheeks, a longer tail that extends past the tips of the folded wings, and a higher-pitched voice (although some calls are similar). The roseate tern (Sterna dougallii) is also similar in size but has a mostly or entirely black bill during the breeding season, much paler gray upperparts, white or very pale pink underparts, a very long tail (longer than that of the Arctic tern), and a distinctively different voice. The least tern (Sterna antillarum) is markedly smaller, with a yellow-orange bill, a white forehead, and a proportionately much shorter tail.

Life cycle and behavior

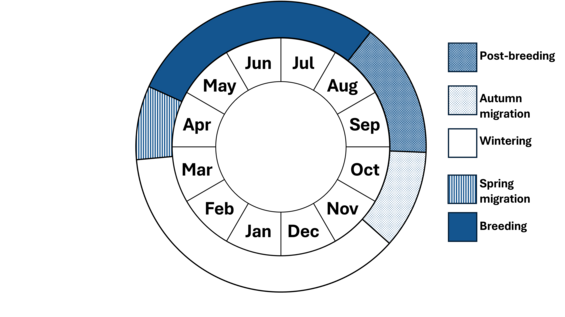

Birds are sighted in Massachusetts waters in mid-April. They begin to alight on the nesting beaches shortly thereafter, spending progressively more time on land engaged in territoriality and courtship as the egg-laying period nears. Egg dates are May 3rd-August 15th. Incubation lasts about 3 weeks, and the nestling period about 3-4 weeks. Massachusetts birds depart from breeding colonies in July and August and concentrate in “staging areas” around Cape Cod and the islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket before beginning southward migratory journeys during August-November.

Figure 1. Phenology in Massachusetts. This is a simplification of the annual life cycle. Timing exhibited by individuals in a population varies, so adjacent life stages generally overlap each other at their starts and ends.

Colony. The common tern is gregarious, nesting in colonies of a few to thousands of pairs. It often breeds in colonies with roseate terns, Arctic terns, black skimmers (Rynchops niger), and, rarely, the least tern. Pairs vigorously defend their nesting territories and may also maintain a linear near-shore feeding territory.

Responses to predators and intruders. The common tern prefers to nest on islands lacking predatory mammals. Eggs and chicks are cryptically colored. Hatched eggshells are removed from the nest site and feces are dispersed (the white of the feces and of the inner shell is obvious).

Colony-nesting seabirds, such as terns, benefit from group defense. Behavioral response to diurnal predators is very variable, and depends on predator species and behavior, stage in nesting cycle, and degree of habituation to threat. Hunting peregrine falcons cause “panics,” during which terns rapidly flee the nesting area and fly over the water; peregrines may delay colony occupation. Many other diurnal predators (including crows, herring and great black-backed gulls, northern harriers, and bald eagles) are “mobbed” (chased and attacked) by terns. Common terns distinguish between hunting and non-hunting gulls and falcons and respond to them differently. Common terns attack human intruders by diving at them, pecking exposed body parts, and defecating on them. Inexperienced birds may merely circle overhead and give alarm calls, whereas more experienced birds may launch intense attacks, to which many researchers will attest. Common terns also distinguish between individual humans, and familiar humans are attacked more vigorously. Attacks intensify as chicks begin to hatch but diminish as chicks mature and become less vulnerable. Adults’ alarm calls cause very young chicks (≤3 days) to crouch motionless, while older, more mobile chicks seek cover.

There is little information on how the common tern responds to nocturnal mammalian predators; however, nocturnal predation by owls and night herons causes terns to abandon the colony at night. This has several consequences: prolonged incubation periods for eggs; chick deaths due to exposure; increased predation on eggs and chicks, particularly by night-herons and ants; and sometimes inattentiveness to eggs by day, which increases egg vulnerability to diurnal predators.

Pair bond and parental care. Courtship involves both aerial and ground displays, including high flights (in which a pair spirals to 30-100 m [~100-330 ft] above ground and then glides down), low flights (in which a fish-carrying male is chased by a female), parading (circling on ground), and scraping. Males feed females during courtship and early incubation. The common tern is socially monogamous but sometimes seeks extra-pair copulations. While both parents incubate eggs and attend chicks, females do more incubating and brooding (especially at night), and males generally do more feeding. Birds of similar age tend to pair. Mate fidelity is high; data from Germany showed that two-thirds of pair bonds were retained from year-to-year; the rest were broken by death or divorce in approximately equal frequencies. Pair-bond durations of up to 14 years have been documented.

Nests. Nests are depressions or “scrapes” in the substrate, to which nesting material, usually dead vegetation or tide wrack, is added throughout incubation. Nest density is highly variable, but usually in the range of 0.06-0.5 nests/m2.

Eggs. Eggs are medium brown, buff, cream, greenish, or olive with dark spots or streaks. Markings are often evenly distributed on the egg, but are often concentrated at the blunt end, especially for the third egg of the clutch, which also may be paler than the first two. Eggs measure approximately 40 x 30 mm (1.6 x 1.2 in) and are sub-elliptical in shape. Clutch size is usually 2-3 eggs, occasionally 1 or 4. Incubation is sporadic until the clutch is complete. The period between laying and hatching is about 23 days for the first egg and about 22 days for the second and third eggs. Incubation shifts last anywhere from <1 minute to several hours.

Young. Chicks are semi-precocial. At hatching, they are downy and eyes are open. They can stand and take food within hours after hatching. They wander away from the nest to seek cover, but remain in the territory at 1-3 days. Chicks are brooded/attended most of the day and night for the first few days of life. Parental attendance drops off after that, except for cold, wet, or hot weather. Parents carry prey to their chicks in their bills. Feeding rates vary by location but are usually on the order of 1-2 feedings per chick per hour. Chicks fledge at 22 to >29 days, but they remain at first within the colony and are still dependent on parents for food. After about a week, they venture out with their parents to the feeding grounds but are unable to catch fish for themselves until 3-4 weeks post-fledging. Families leave the colony 10-20 days after chicks fledge and remain together during the staging period. Little is known of family cohesion during migration.

Diet and foraging. The common tern feeds mainly on a wide variety of small fish; frequently, it includes squid, crustaceans, and insects in its diet. The primary prey item in most Atlantic coast breeding colonies is the sand lance. In Massachusetts, herring, hake, silversides, cunner, bay and striped anchovy, squid, and shrimp are also important; pipefish and butterfish are taken, especially when other prey are scarce, but chicks are rarely able to swallow them. Over water, the common tern captures food by plunge-diving (diving from heights of 1-6 m [3-20 ft] and submerging to ≤50 cm [≤20 in]), diving-to-surface, and contact-dipping; it catches flying insects, including flying ants, on the wing. It often forages singly or in small groups, but it may congregate in feeding flocks of 1,000 birds, especially over schools of predatory fish that drive smaller prey to the surface. It commonly feeds in association with roseate and Arctic terns, and sometimes gulls.

Demography and survival. In Massachusetts, most common terns breed annually starting at 3 years, some at 2 or 4 years. As birds age, they nest progressively earlier in the season. Only one brood per season is raised, but birds renest 8-12 days after losing eggs or chicks. Productivity is highly variable and may range from zero to >2.5 chicks fledged per pair, depending on food availability, nest overwash, and predation. Productivity increases with age through the lifetime of the bird. Survival from fledging to 4 years was estimated at about 10% for Massachusetts birds. Annual survival of adults in Massachusetts was estimated at about 80-90%, depending on age. The oldest documented wild common tern is a Massachusetts-hatched individual encountered alive at age 29 years.

Population status

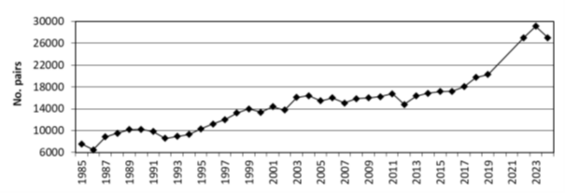

The common tern is listed as a species of Special Concern in Massachusetts. Populations are well below levels reported pre-1870, when hundreds of thousands reportedly bred. Egging probably limited populations throughout the 1700s and 1800s. More seriously, hundreds of thousands were killed along the Atlantic coast by plume-hunters in the 1870s and 1880s, reducing the population to a few thousand at fewer than ten known sites by the 1890s. In Massachusetts, only 5,000 to 10,000 pairs survived, almost exclusively at Penikese and Muskeget Islands. The state’s population grew to 30,000 pairs by 1920, following the protection of the birds in the early part of the century. Populations subsequently declined through the 1970s, reaching a low of perhaps 7,000 pairs, largely as a result of the displacement of terns from nesting colonies by herring gulls and, later, great black-backed gulls. Since then, numbers have edged upward with a rapid uptick after 2019 (Figure 2). In 2024, 27,019 pairs nested, with about 90% of them concentrated at just three sites: Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge, Chatham (19,075 pairs); Ram Island, Mattapoisett (2,710 pairs); and Bird Island, Marion (2,709 pairs).

Figure 2. Number of nesting common tern pairs in Massachusetts, 1985 – 2024.

Distribution and abundance

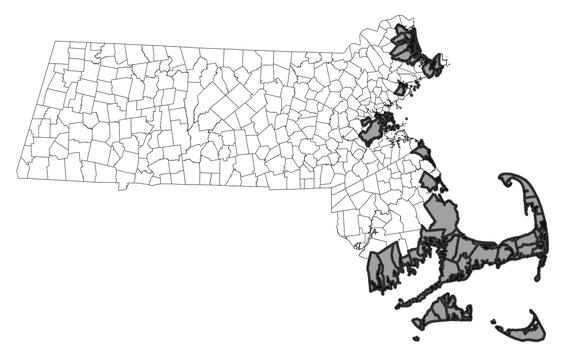

Outside the breeding season, the common tern is widely distributed primarily at temperate latitudes. It breeds in the northern hemisphere, principally in the temperate zones of Europe, Asia, and North America, and at scattered tropical and sub-tropical locations. In North America, it breeds along the Atlantic Coast from Labrador to South Carolina, and along lakes and rivers as far west as Montana and Alberta. In 2024, common terns nested at 38 sites in Massachusetts, with the largest breeding colonies located on Cape Cod and in Buzzards Bay. After the breeding season, Massachusetts birds move to pre-migratory staging areas around Cape Cod and the islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket before departure for wintering grounds. Common terns feed offshore and return to the staging areas to rest and roost. During August-October, birds depart from staging areas and begin migrating southward. Along the way, they rest on the water and along Caribbean and South American shorelines before reaching their final destinations. With advances in tracking technology, migratory staging and wintering areas for this population have become better understood in recent years. Birds breeding on the Atlantic coast winter along the north and east coasts of South America, south to Argentina. However, much more information about distribution and ecology on the migratory staging and wintering grounds remains to be discovered.

Distribution in Massachusetts. 1999-2024. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

In Massachusetts, the largest common tern colonies are on sandy, gravelly, or cobbly islands, but they also nest on barrier beaches, salt marshes, small rocky islands, dilapidated docks, purpose-built platforms, and bridge abutments. The species prefers areas with scattered vegetation, which is used for cover by chicks. Along the Atlantic coast, most breeding birds forage within 20 km (12 mi) of colonies and often within 1 km (0.6 mi) of shore, frequently in bays, tidal inlets, or between islands. Post-breeding staging areas are typically tidal flats, sandbars, or low-lying barrier island beaches.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

An adult common tern feeds its fledgling over open water.

Threats

Habitat loss: Nesting and staging habitat is threatened by overwash and erosion of low-lying areas, rising sea levels, and increasing frequency and intensity of storms due to climate change. Proliferation of invasive vegetation degrades nesting habitat. High human disturbance is a feature of many Northeast staging sites, causing repeated flushing of flocks with probable separations of parents and still-dependent young, and some more accessible breeding sites.

Predators. In North America, predators of common tern eggs, young, and adults include a wide variety of birds and mammals, snakes, ants, and land crabs. Nocturnal predators are particularly disruptive, causing nest or site abandonment, adult mortality, and loss of eggs and chicks from predation and exposure. Nocturnal mammals (especially fox, mink, and rat; sometimes skunk, raccoon, feral cat, weasel, and coyote) are the most important predators in mainland or near-shore colonies. At islands further from the mainland, herring and great black-backed gulls, great horned owl, and black-crowned night-heron (all of which are active primarily or, in the case of gulls, often, at night) are important avian predators. American crow, ruddy turnstone, and peregrine falcon can also be significant predators.

Climate change: In addition to climate-induced habitat loss from rising sea levels and storms, the rapid warming of the northwest Atlantic Ocean may result in changes in prey distribution, abundance, and/or phenology. The common tern, like many seabirds, does not appear to be shifting the timing of breeding in response to warming seas.

Contaminants: Contaminants have had negative impacts on common terns. Locally, they were impacted by the release of PCBs into the New Bedford Harbor area from the 1940s through the 1970s; they were exposed to toxic levels of PCBs and possibly DDE. The 2003 Bouchard 120 oil spill in Buzzards Bay had negative impacts on common terns and degraded their nesting habitat.

Wind farms: The construction and operation of offshore wind turbines, which are poised to proliferate in the Northeast, may cause changes to prey availability, displacement from foraging habitat, and mortality from collisions.

Disease and biological toxins: To date, diseases have not had a major impact on common terns in Massachusetts. However, diseases, including emerging ones such as HPAI, potentially could have large impacts in the future. Paralytic shellfish poisoning associated with “red tide” events has occasionally been significant.

Wintering grounds: Knowledge of threats on the wintering grounds is substantially incomplete. The species is less protected outside of the breeding area. Persecution by humans (trapping for food) on the wintering grounds may affect common terns nesting in the Northeast. In recent years, substantial numbers of roseate and common terns have been killed by coastal powerlines in Brazil, and international cooperative efforts are underway to mitigate this loss. The development of coastal habitat for tourism infrastructure is an ongoing threat.

Plastics: Plastic trash in the environment poses a threat as it can be mistaken as food by seabirds and shorebirds and ingested or cause entanglement. Ingested plastics, common for seabirds, can block digestive tracts, cause internal injuries, disrupt the endocrine system, and lead to death. Entanglement from fishing gear and other string-like plastics can cause mortality by strangulation and impairing movements.

Conservation

The common tern is a conservation-dependent species. Populations in Massachusetts continue to be threatened by predators, displacement by gulls, and erosion. Also, should established nesting colonies be disrupted, lack of suitable (i.e., predator-free) alternative nesting sites is a serious concern in the state.

Lethal gull control (initially), continual gull harassment, and predator control at South Monomoy, Ram, and Penikese Islands have resulted in thriving tern colonies at these restored sites. Tern restoration is a long-term commitment that requires annual monitoring and management to track progress, identify threats, manage vegetation, prevent gulls from encroaching on colonies, and remove predators.

Nesting: Tern protection and restoration are ongoing, long-term commitments that require regular management and monitoring to track progress, identify threats, control vegetation, prevent gulls from encroaching on colonies, and remove predators. Annually, colonies are protected by the posting of signs, presence of wardens, and/or exclusion of visitors and their pets. Vegetation control is sometimes necessary when it is dense enough to impede adults’ ability to access nesting sites or feed young, or when it degrades habitat.

Because of the regional importance of Massachusetts to the common tern, several restoration projects have been initiated in the state. The stabilization and nourishment of Bird Island, MA in 2015-2018 doubled the amount of roseate and common tern nesting habitat and resulted in major increases of both species at the site. Common and roseate terns were successfully restored to Ram Island after a gull control program in 1990-1991; a nourishment project in 2010-2011 countered erosion of nesting habitat; and as of 2025, a major habitat restoration project is in the design phase. A restoration program at Monomoy NWR, begun in 1996, encouraged the expansion of a huge colony of common terns; at about 20,000 pairs in 2024, it is perhaps the world’s largest colony of this species. A project at Penikese Island, in Buzzards Bay that began in 1998 involves discouragement of gulls from small portions of the island and managing predators and vegetation; today the island supports one of the state’s largest common tern colonies.

Staging: Protecting flocks from disturbance by people and their pets is necessary to allow terns to rest and feed to prepare for migration.

Wintering: Much more information about distribution, ecology, and threats on the wintering grounds is needed to facilitate conservation. International cooperation is and will continue to be essential to the protection of this species, which spends half of the year outside of North America.

Plastics: Avoid or recycle single-use plastics and promote and participate in beach cleanup efforts.

Acknowledgments

Beach-nesting birds in Massachusetts are protected and managed by an extensive network of highly dedicated and conservation-minded landowners, individuals, organizations, and agencies. The birds’ successes are their successes.

References

Arnold, J. M., S. A. Oswald, I. C. T. Nisbet, P. Pyle, and M. A. Patten (2020). Common tern (Sterna hirundo), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Bird Banding Laboratory. North American Bird Banding Program Longevity Records. Version 2023.2. Eastern Ecological Science Center. US Geological Survey. Laurel, MD.

Blodget, B.G., and S.M. Melvin. Massachusetts tern and Piping Plover Handbook: A Manual for Stewards. Westborough, MA: Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, 1996.

Catlin DH, Gibson D, Hunt KL, Weithman CE, Boettcher R, Gwynn R, Karpanty SM, Fraser JD, Ritter S, Maxwell SM. Movement patterns of foraging common terns (Sterna hirundo) breeding in an urban environment in coastal Virginia. PLoS One. 2024 Jul 11;19(7):e0304769. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0304769. PMID: 38991012; PMCID: PMC11238962.

Keogan, K., Daunt, F., Wanless, S., Phillips, R. A., Walling, C. A., Agnew, P., … C. Mostello … … Lewis, S. 2018. Global phenological insensitivity to shifting ocean temperatures among seabirds. Nature Climate Change 8: 313 – 318.

Loring P. H., P. W. Paton, J. D. McLaren, H. Bai, R. Janaswamy, H. F. Goyert, C. R. Griffin, and P. R. Sievert. 2019. Tracking Offshore Occurrence of common terns, Endangered Roseate terns, and Threatened Piping Plovers with VHF Arrays. Sterling (VA): US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. OCS Study BOEM 2019-017.

Nacci, D. E., M. E. Hahn, S. I. Karchner, S. Jayaraman, C. S. Mostello, K. M. Miller, C. Gilchrist Blackwell, and I. C. T. Nisbet. 2016. Integrating monitoring and genetic methods to infer historical risks of PCBs and DDE to common and roseate terns nesting near the New Bedford Harbor Superfund Site (Massachusetts, USA). Environ. Sci. Technol. 50 (18): 10226-10235.

Nisbet, I.C.T. “common tern (Sterna hirundo).” 2002. The Birds of North America, No. 618 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). Philadelphia, PA: Birds of North America, Inc.

Nisbet, I. C. T., C. S. Mostello, R. R. Veit, J. Fox and V. Afanasyev. 2011. Migrations and Winter Quarters of Five common terns Tracked using Geolocators. Waterbirds 34(1):32-39.

Nisbet, I. C. T., P. Szczys, C. S. Mostello, and J. W. Fox. 2011. Female common terns Sterna hirundo start autumn migration earlier than males. Seabird 24:103-106.

Nisbet, I. C. T. & Mostello, C. S. 2015. Winter quarters and migration routes of common and roseate terns revealed by tracking with geolocators. Bird Observer 43: 222-231.

Oswald, S.A., Nisbet, I. C. T., & Mostello, C. S. 2023. Common terns Sterna hirundo and Roseate terns Sterna dougallii frequently rest on the sea surface in winter quarters and during migration, Bird Study, DOI: 10.1080/00063657.2023.2237232

Paton, P. W. C., P.H. Loring, G.D. Cormons, K.D. Meyer, S. Williams, and L.J. Welch. 2020. Fate of common (Sterna hirundo) and Roseate terns (S. dougallii) with Satellite Transmitters Attached with Backpack Harnesses. Waterbirds 43(3-4), 342-347

Tims, J. L., I. C. T. Nisbet, M. S. Friar, C. S. Mostello, and J. J. Hatch. 2004. Characteristics and performance of common terns in old and newly-established colonies. Waterbirds: 27(3): 321-332.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. (Accessed 2/24/25) International partners respond to roseate tern deaths in Brazil. https://www.fws.gov/story/teaming-terns

Veit, R.R., and W.R. Petersen. Birds of Massachusetts. Lincoln, MA: Massachusetts Audubon Society, 1993.

Contact

| Date published: | April 24, 2025 |

|---|