- Scientific name: Somtatochlora georgiana

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Male coppery emerald

The coppery emerald (Somatochlora georgiana) is a large insect of the order Odonata, sub-order Anisoptera (the dragonflies), and family Corduliidae (the emeralds). Most striped emeralds (Somatochlora) are large and dark with at least some iridescent green coloration, brilliant green eyes in mature adults (brown in young individuals), and moderate pubescence (hairiness), especially on the thorax. The coppery emerald is distinctive among Somatochlora in completely lacking the usual metallic coloration of the face, thorax and abdomen (section behind the thorax), and in the lack of green eyes, even in mature adults. The face and back of the head are pale brown in coloration, lighter on the face than on the back of the head. The large eyes, which meet at a seam on the top of the head, are chestnut-colored. The thorax is dull brown with two yellowish white stripes on each side of the thorax, which may become obscured with age. The slender, cylindrical abdomen is brownish yellow, darkening towards the tip to a reddish brown. The wings of this species are transparent and, as in all dragonflies and damselflies, are supported by a dense system of dark veins.

Adult coppery emeralds range from 45 to 49.5 mm (1.75 to 2 in) in length. Both sexes are similar in coloration and body form, though the females tend to be larger. Final instar nymphs may range from 17.5 to 19.6mm (0.68 to 0.77 in) in length.

Adult coppery emeralds are the smallest striped emerald species and are similar in size to the ocellated emerald (S. minor) and the brush-tipped emerald (S. walshii). However, the coppery emerald can be easily distinguished from these species by its lighter brown and lack of metallic coloration (other species are much darker). The shapes of the terminal appendages in the males and the vulvar lamina in the females are also distinctive (Lam 2024). May be confused with other dragonflies of similar size and general colorization including baskettails (Epitheca), but lack the features as described above.

The nymphs and exuviae can be distinguished by characteristics as per the keys in Needham et al. (2000), Soltesz (1996), and Tennessen (2019).

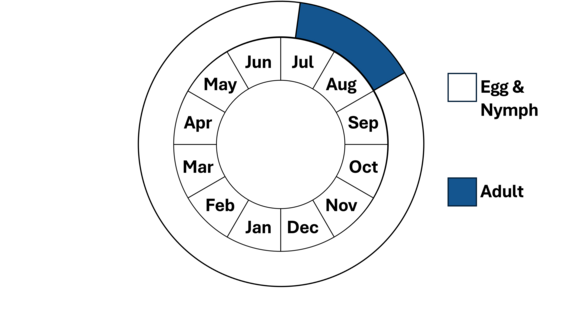

Life cycle and behavior

Note, nymphs are present year-round.

As with other Odonates, coppery emerald goes through aquatic egg and nymph life stages, and a terrestrial adult stage. The cryptic nymphs are predators, feeding on a wide variety of aquatic insects, small fish, and tadpoles. Nymphs undergo several molts (instars) for at least 1 year until they are ready to emerge as winged adults. Nymphs emerge up onto emergent vegetation, exposed banks, or tree trunks. When the nymph reaches a secure substrate, the adult begins to push itself out of the exoskeleton. As soon as the abdomen and wings are fully expanded, the adult takes its first flight. This maiden flight usually carries the individuals up into surrounding forest or other areas away from water, where they spend several days maturing and feeding and are somewhat protected from predation and inclement weather. Coppery emeralds may be found in fields and forest clearings foraging on small aerial insects, such as flies and mosquitoes, which are consumed while flying. The species is most active during midday and evenings and may join feeding swarms with other species. When at rest, coppery emeralds hang vertically or perch obliquely from tree or shrub branches. After about a week, the adult coloration is acquired, and the dragonfly becomes sexually mature before returning to the breeding habitat to initiate mating.

Breeding in Massachusetts probably occurs from early July through August, as in other regions where this species occurs. Males patrol along streams in search of females and driving off competing males. A joined male-female pair quickly flies off into the surrounding upland habitat to mate. Following mating, oviposition (egg-laying) occurs. Females of the genus Somatochlora, oviposit alone and deposit their eggs directly into the substrate by tapping the tip of the abdomen on its surface while still in flight.

In Massachusetts, coppery emerald adults have been encountered from early July to late-August.

Distribution and abundance

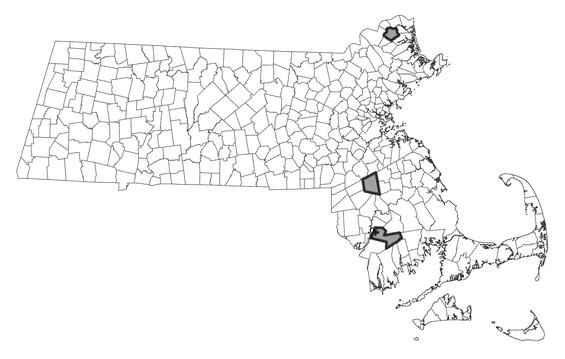

The coppery emerald is very rare and local throughout its range. Despite its scarcity, it is generally distributed on the coastal plain of the southeastern United States, from Texas east to Florida and north to Virginia, New Jersey, and into Massachusetts as its northern extent. In Massachusetts, coppery emerald inhabits eastern parts of the state, specifically in the Merrimack, Ipswich, Charles, and Taunton River watersheds. In Massachusetts, they have only been recorded at 6 sites in last 50 years, with oviposition recorded at one site.

The scarcity of the coppery emerald in Massachusetts may be due to its northern range limit, survey effort, and habitat suitability. Coppery emerald has been observed in abundance on few occasions, but most observations are of single individuals.

The coppery emerald is listed as endangered in Massachusetts. As with all species listed in Massachusetts, individuals of the species are protected from take (picking, collecting, killing, etc.) and sale under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

In Massachusetts, the coppery emerald has been found most often away from potential breeding habitats in fields and forest clearings. However, many of these areas are adjacent to habitats that, based on observations elsewhere in this species’ range, are appropriate breeding sites. Breeding sites and nymphal habitat for this species are low gradient small sandy streams that flow through woods or swamps. The coppery emerald has been found breeding in a small, sluggish stream through a white cedar swamp.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Potential stream habitat for coppery emerald

Threats

Threats to coppery emerald include degradation to water quality from run-off like salt, pesticides and herbicides, discharge of industrial and chemical pollutants, accelerated eutrophication, and loss of upland and riparian forests also needed for adult development. Coppery emerald may also be vulnerable to anthropogenically-induced streamflow alteration, such as water withdrawals and damming. More severe drought via climate change may pose a threat for coppery emerald considering its habitat are small streams.

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

Surveys should target known sites and new streams and wetlands to inform coppery emerald occupancy and population status in Massachusetts. Surveys for adults are likely to be more effective for detection compared to nymph or exuvia as this life stage is extremely difficult to find. Adult surveys should target breeding and feeding habitats, including swarms, where detection might be most probable. Multiple site visits (e.g., ≥3) are likely required to detect this species because of its rarity and the difficulty to capture by net or camera. Sites with breeding evidence should be monitored every 5 years to document changes in occupancy and habitat conditions. Sites without breeding evidence require additional survey effort to conform breeding and nymphal habitat. Suitable stream and wetland habitat likely exists across the landscape as more sites have been identified in recent years. Effort should be devoted to surveys in new potential sites to further update coppery emerald status in Massachusetts.

Management

Upland and wetland protection to maintain water quality and quantity is critical for the conservation of coppery emerald. Protection of forested upland borders of these river systems are critical in maintaining suitable water quality and are critical for feeding, resting, and maturation. Development of these areas should be discouraged, and the preservation of remaining undeveloped uplands should be a priority. Alternatives to commonly applied road salts should tested to minimize freshwater salinization.

Research needs

Research effort is needed to estimate occupancy and detection rates for this species as it likely inhabits other sites not previously surveyed and species detection is likely low. Further refinement is needed to identify species habitat requirements. Species distribution models coupled with climate change projections are needed to help assess future species risk and identify climate-resistant stream and wetland sites.

References

Dunkle, Sidney W. Dragonflies Through Binoculars. Oxford University Press, 2000.

Lam, E. Dragonflies of North America. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2024.

Needham, J.G., M.J. Westfall, Jr., and M.L. May. Dragonflies of North America. Scientific Publishers, 2000.

Nikula, B., J.L. Ryan, and M.R. Burne. A Field Guide to the Dragonflies and Damselflies of Massachusetts. 2nd ed. Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, 2007.

Paulson, D. Dragonflies and Damselflies of the East. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Soltesz, K. Identification Keys to Northeastern Anisoptera Larvae. Center for Conservation and Biodiversity, University of Connecticut, 1996.

Tennessen, K. Dragonfly Nymphs of North America: An identification guide. Springer, 2019.

Walker, E.M. 1958. The Odonata of Canada and Alaska, Vol. II. University of Toronto Press.

Contact

| Date published: | March 6, 2025 |

|---|