- Scientific name: Sagittunio nasutus

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Special Concern (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Eastern pondmussel

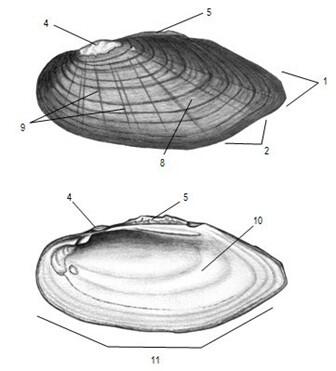

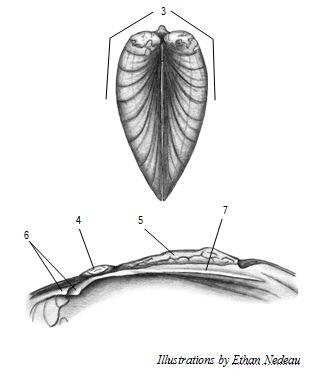

The eastern pondmussel is a medium-sized to large mussel that may exceed 150 mm (6 in) in length. The shape is distinctly elongate or elliptical and the posterior end tapers to a blunt point (1). Shells of sexually mature females may be slightly more rounded toward the posterior ventral margin (2) than males or adolescent females. Shells are laterally compressed (3), and despite being thin, they are quite strong. Beaks are low (4) and barely extend beyond the line of the hinge (5). Hinge teeth are well developed but delicate; the left valve has two pseudocardinal teeth and two lateral teeth, and the right valve has two pseudocardinal teeth (6) and one lateral tooth (7). The periostracum (8) is yellowish or greenish-black in young individuals, but usually dark brown or black in older specimens. Shell rays (9) are sometimes evident on those individuals with a light-colored periostracum. The nacre (10) is usually purple, pink, or silvery-white.

Due to its elongate shape (11), pointed posterior end (1), and laterally compressed shell (3), the eastern pondmussel is easy to distinguish from all other species in Massachusetts.

Life cycle and behavior

Eastern pondmussels are essentially sedentary filter feeders that spend most of their lives partially burrowed into the bottoms of rivers, streams, lakes, and ponds. Eastern pondmussels, like all freshwater mussels, have larvae (called glochidia) that must attach to the gills or fins of a vertebrate host to develop into juveniles. Sexually mature female eastern pondmussels use papillae along their mantle margins to lure potential host fish; this behavior was described by Corey et al. (2006). Displaying females tend to migrate toward the surface of the sediment, and may even lie fully unburied on the surface of the sediment to increase their visibility to fish. They will also part their valves widely, exposing more of the mantle edge. Host fish lab experiments for this species indicate several potential hosts including yellow perch, pumpkinseed, bluegill, redbreast sunfish, and largemouth bass (Eads et al. 2015). These fish species occur throughout the eastern pondmussel’s range and may be actual hosts in Massachusetts. Little else is known about the biology of the eastern pondmussel.

Distribution and abundance

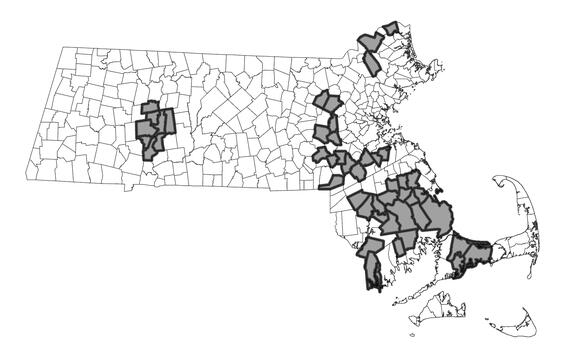

The eastern pondmussel is distributed throughout Atlantic coastal drainages from Virginia to New Hampshire and in the eastern Great Lakes region. In Massachusetts, the species occurs in Middle Connecticut, Merrimack, Concord, Charles, Taunton, Cape Cod, and other coastal river watersheds. It is most abundant in southeastern Massachusetts, particularly in large coastal plain ponds on the mainland and Cape Cod. Small populations also occur in the central Connecticut River Valley, especially in low-gradient sections of several tributaries to the Connecticut River.

The eastern pondmussel is a species of Special Concern in Massachusetts. A few sizeable populations exist in coastal plain ponds of eastern Massachusetts; however, riverine populations in the state are generally sparse except for a couple of tributaries to the Connecticut River. Most populations are of apparently small sizes with little evidence of recent reproduction. Surveys of historic sites and a careful status review are needed.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

The eastern pondmussel inhabits low gradient streams, rivers, and small to large lakes and ponds. It exhibits no distinct preference for substrate (mud to cobble) and depth but may prefer slower flows. It has been found at relatively high densities at depths of 4.5-7.6 m (15-25 ft) in coastal ponds where the substrate was primarily mud (Nedeau and Low 2008), and in shallow rivers with relatively strong currents and a substrate of gravel and cobble (Nedeau 2008). In the Connecticut River watershed, populations are known primarily from streams and rivers (Nedeau 2008), but in eastern Massachusetts, including Cape Cod, lake and pond populations are more prevalent.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Lake habitat typical for eastern pondmussel.

Threats

Because eastern pondmussels are essentially sedentary filter feeders, they are unable to flee from degraded environments and are vulnerable to the alterations of water bodies. Eastern pondmussels occur in lakes and rivers, and the threats in these two habitats are different. Overlapping threats include nutrient enrichment, sedimentation, other forms of pollution, non-native and invasive species, and the many consequences of urbanization. River populations of eastern pondmussels are threatened by alteration of natural flow regimes, encroachment of river corridors by development, habitat fragmentation caused by dams, and a legacy of land use that has greatly altered the natural dynamics of river corridors (Nedeau 2008). Lake populations are challenged by intense development, modification, and recreational use of sensitive shoreline habitats, accelerated eutrophication, and more frequent cyanobacteria blooms. Dams and other stream barriers in the rivers that connect lakes to coastal waters may also affect lake populations of eastern pondmussels. Invasive plants and animals, such as European milfoil and basket clam (Corbicula fluminea), are having severe impacts on the fragile ecology of coastal plain ponds. The ultimate consequences on eastern pondmussels and other native species are not completely known, but the prognosis is bleak. In addition, the long-term effects of regional or global problems such as acidic precipitation, mercury, and climate change are considered severe but little empirical data relates these stressors to mussel populations. In combination with the above stressors (e.g., water withdrawals, eutrophication), effects from climate change including sustained droughts and warmer water temperatures threaten eastern pondmussel populations by reducing water levels, and creating more suitable conditions for cyanobacteria blooms particularly in lentic systems that have shown to cause mussel kills.

Freshwater mussel tracks in exposed substrate as a result of low water levels caused by prolonged drought and water withdrawal.

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

Standardized surveys are critically needed to monitor known populations, evaluate habitat, locate new populations, and assess population viability at various spatial scales (e.g., stream, watershed, state). Survey efforts should continue to search for new populations via physical and potentially eDNA surveys, particularly in coastal watersheds and expand our knowledge on species distribution in extant watersheds every 5 years or to the extent feasible. Establishment of long-term monitoring sites in extant watersheds is needed to acquire critical demographic and population trend data. Monitoring these sites should occur annually in multi-year blocks or as needed.

Management

Discovery and protection of viable mussel populations is critical for the long-term conservation of freshwater mussels. Currently, much of the available mussel occurrence data are the result of limited presence/absence surveys. In addition, regulatory protection under MESA only applies to rare species occurrences that are less than 25 years old. Surveys are critically needed to monitor known populations, evaluate habitat, locate new populations, and assess population viability so that conservation and restoration efforts, as well as regulatory protection, can be effectively targeted. Coastal plain ponds are critical to the long-term viability of the eastern pondmussel in Massachusetts, and these habitats are also experiencing intense development pressure and recreational use. Understanding this threat and developing conservation and management strategies is a high priority for NHESP. Other conservation and management recommendations include: understand the effects of shoreline development and recreational use of lakeshores; maintain naturally variable river flows and lake water levels, and limit water withdrawals; identify, mitigate, or eliminate sources of pollution, including excess nutrients, to water bodies; identify dispersal barriers for host fish, especially those that fragment the species range within a river or watershed, and seek options to improve fish passage or remove the barrier; maintain adequate vegetated riparian buffers along rivers and lakes; and protect or acquire land at high priority sites.

Research needs

Research needs for eastern pondmussel include population-level data on survival rate, mortality rate, individual growth rates, population size trends, age at reproduction, sex ratio, and age structure. This data will help develop population viability models to identify when populations may need active restoration. A better understanding of host fish relationships is needed; this information might help guide fisheries management at the fishways. Habitat mapping of large rivers can aid in evaluation of suitable physical habitat and direct future survey effort. Climate change projections for water temperature and water levels in occupied and potential watersheds for species introduction are also needed to assess current and future population risks to drought and cyanobacteria blooms and identify potential refuges. Investigation of impacts of invasive species, particularly basket clam (Corbicula fluminea), on eastern pondmussel is needed. Additionally, species-specific physiological tolerances to commonly used and novel herbicides are needed.

References

Corey, C.A., R. Dowling, and D.L. Strayer. 2006. Display behavior of Ligumia (Bivalvia: Unionidae). Northeastern Naturalist 13(3): 319-332.

Eads, C.B., J.E. Price, and J.F. Levine. 2015. Fish hosts of four freshwater mussel species in the Broad River, South Carolina. Southeastern Naturalist 14(1):85-97.

Lefevre, G., and W.C. Curtis. 1911. Metamorphosis without parasitism in the Unionidae. Science 33: 863-865.

Nedeau, E.J. 2008. Freshwater Mussels and the Connecticut River Watershed. Connecticut River Watershed Council, Greenfield, Massachusetts. xviii+ 132 pp.

Nedeau, E.J., and J. Victoria. 2003. A Field Guide to the Freshwater Mussels of Connecticut. Connecticut Department of Environmental Protection, Hartford, CT.

Nedeau, E.J., M.A. McCollough, and B.I. Swartz. 2000. The Freshwater Mussels of Maine. Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife, Augusta, Maine.

Raithel, C.J., and R.H. Hartenstine. 2006. The Status of Freshwater Mussels in Rhode Island. Northeastern Naturalist 13(1): 103-116.

Vaughn, C. 1993. Can biogeographic models be used to predict the persistence of mussel populations in rivers? pp.117-122 in K.S Cummings, A.C. Buchanan and L.M. Koch (eds)., Conservation and Management of Freshwater Mussels: proceedings of a UMRCC symposium, 12-14 October 1992, St. Louis, Missouri. Upper Mississippi River Cons. Com., Rock Island, Illinois. 189 pp.

Contact

| Date published: | March 28, 2025 |

|---|