- Scientific name: Williamsonia fletcheri

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Male ebony boghaunter

The ebony boghaunter (Williamsonia fletcheri) is a small, delicately built, blackish dragonfly (order Odonata, sub-order Anisoptera) in the family Corduliidae (the emeralds). Ebony boghaunters are dull black in color, with bright green (male) or grey (female) eyes, metallic brassy green frons (the prominent bulge on the front of the head), and a yellow-brown labium. The black abdomen has a pale yellow-white ring between the 2nd and 3rd abdominal segments, and a less conspicuous ring between the 3rd and 4th segments. Females are similar to the males, but have thicker abdomens, shorter terminal appendages at the tip of the abdomen, and are paler in coloration.

Ebony boghaunters range in length from 29-35mm (1.1-1.4 in) with males averaging slightly larger. The wings are about 22 mm (1.1 in) long and hyaline (transparent and colorless), except for a very small amber patch at the base. The nymph was undescribed until recently (Charlton and Cannings, 1993). When fully developed, the nymphs range from 15-17mm (0.59-0.67 in; Tennessen 2019).

The genus Williamsonia comprises just two species. The ringed boghaunter (W. lintneri) is similar in appearance to the ebony boghaunter; both occupy roughly similar habitats and although rare may co-occur at a few sites. The ringed boghaunter is somewhat paler in coloration than the ebony boghaunter, has dull orange rings on each abdominal segment, and has blue-grey eyes in both sexes. The ebony boghaunter has only one or two prominently colored yellow-white rings near the base of the abdomen, and the eyes of mature males are bright green. The petite emerald (Dorocordulia lepida) has a flight season overlapping that of ebony boghaunter and is similar in its dark overall coloration, slight build, and metallic green frons with a yellow-brown labium. However, the petite emerald is slightly larger with a metallic luster on its thorax, lacks abdominal rings, and has brilliant green eyes when mature. Another dragonfly, the frosted whiteface (Leucorrhinia frigida), also flies early in the season and occurs in the same habitat. It is similar in size and general appearance, the mature males being black in coloration. However, they have a grayish patch at the base of the abdomen and a white face. Other species of Leucorrhinia also have a superficial resemblance and overlapping flight seasons but can be distinguished from ebony boghaunters by their white faces and differing abdominal patterns.

Life cycle and behavior

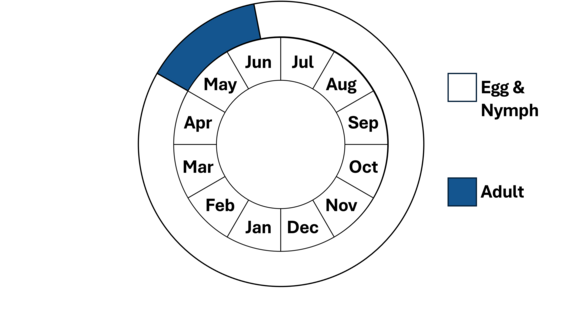

Note, nymphs are present year-round.

The life cycle of the ebony boghaunter is poorly known. The eggs and nymphs are fully aquatic. The cryptic nymphs are predators and presumably feed mostly on smaller aquatic invertebrates. Nymphs are usually highly localized and clustered sometimes at high densities (Tennessen 2019). Nymphs undergo several molts (instars) for at least 2 years until they are ready to emerge as winged adults. Nymphs emerge up onto emergent vegetation, exposed substrates, or tree trunks. When the nymph reaches a secure substrate, the adult begins to push itself out of the exoskeleton. As soon as the abdomen and wings are fully expanded, the adult takes its first flight. This maiden flight usually carries the individuals up into surrounding forest or other areas away from water, where they spend several days maturing and feeding and are somewhat protected from predation and inclement weather. Nymphs emerge from the water in May to transform into winged adults. Larval habitat is not well known but may be similar to that of the ringed boghaunter, whose larvae develop in shallow pools 15-30 cm (6-12 in) deep, among sphagnum mats. At one Massachusetts site, a recently emerged adult was found clinging to a small leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata) shrub about a foot above the sphagnum mat and an exuviae was found nearby, also attached to a leatherleaf stalk.

Adults are most often found along dirt roads and trails, or in small clearings in woodlands near breeding sites. However, they can be very inconspicuous due to their small size, dark coloration, and rather sedentary behavior. They typically perch in small sunlit patches of the forest floor on logs or vertically on tree trunks, occasionally making brief flights to capture small insect prey. Mating behavior has been observed only rarely. Although it has been suggested that the species is not territorial, at one Massachusetts site males were observed exhibiting apparently territorial behavior over soupy sphagnum at a bog/pond interface. The males actively chased, and were chased by, others of their own species as well as by male Hudsonian whitefaces (Leucorrhinia hudsonica). Mating pairs have been seen at the periphery of bogs and in woodland openings nearby. After mating, the females are thought to oviposit alone in the bog pools, depositing their eggs in flight by tapping the water surface with the tip of their abdomens.

Ebony boghaunters first appear in May and are on the wing into mid-June.

Distribution and abundance

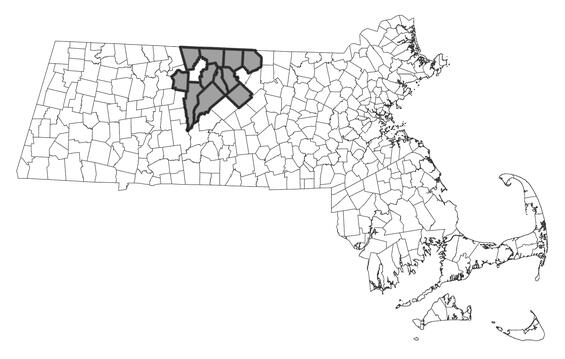

The ebony boghaunter appears to be very local in distribution and is considered a glacial relict. It has been found only in widely scattered bogs from Nova Scotia and New Brunswick west to Manitoba, and south to Minnesota, Michigan, Wisconsin, New York and Massachusetts, which is its most southern range extent in New England. In Massachusetts, the species occurs at relatively higher elevational wetlands in the Middle Connecticut, Millers, Chicopee, and Nashua watersheds. Many occupied sites are larger wetland complexes, are on protected land, and continue to support the species over the past 25+ years as documented from more recent survey efforts. Observed species abundances are typically low (<5 individuals) and may reflect a combination of small population size and/or low detection rates because of their cryptic habit. However, a few sites support relatively higher recorded abundances.

The ebony boghaunter is listed as Endangered in Massachusetts. As with all species listed in Massachusetts, individuals of the species are protected from take (picking, collecting, killing, etc.) and sale under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Ebony boghaunters inhabit wet sphagnum bogs and swampy northern peatlands, often with soupy sphagnum pools, typically adjacent to coniferous or mixed coniferous/deciduous woodlands where the adults hunt and roost. Their specific habitat requirements, however, are not well understood, as they seem to be absent from many apparently suitable wetlands within the species’ range.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Example of bog habitat associated with ebony boghaunter.

Threats

The primary threat to ebony boghaunter is wetland, riparian, and upland habitat destruction through physical alteration or pollution. In some portions of its range, the ebony boghaunter’s habitat is under pressure from development, logging, and peat mining interests. Artificial changes in water level from anthropogenic or beaver sources, and various forms of pollution, such as road and agricultural runoff, septic system failure, and insecticides, are also potential threats.

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

Surveys should continue to target known sites and new wetlands to determine ebony boghaunter detection and occupancy rates. The species likely occupies other sites in Massachusetts particularly in north central and western Massachusetts. Surveys should target adults in basking and breeding habitats, where the species is mostly likely to be detected. The species is most often observed away from wetlands on nearby dirt roads, trails, or sunny patches within the forest. Later in the flight period, the species may be best surveyed in wetlands where breeding might occur. Multiple site visits (e.g., >3) are likely required to detect this species because of its rarity and its difficulty to capture by net or camera. Prioritized sites should be monitored at least every 5 years to document changes in occupancy and habitat conditions.

Management

Protection of wetlands and its surrounding upland habitat is crucial for ebony boghaunter persistence in Massachusetts. Upland habitats adjoining the breeding sites should be maintained for roosting, hunting, and for newly emerged adults that are more susceptible to mortality from predation and inclement weather. Development of these areas should be discouraged, and the preservation of remaining undeveloped uplands should be a priority. Alternatives to commonly applied road salts should tested to minimize freshwater salinization. Other actions to improve or prevent habitat degradation include reduction of nutrient, agricultural and road runoff; minimization of water level alteration and groundwater withdrawals; prevention and management of nonnative aquatic vegetation; limitation and enforcement of off-road vehicles in wetland habitat; and upland connection between ponds. Many known sites are on protected land and managers of these properties should be advised the species habitat requirements.

Research needs

Research effort is needed to estimate occupancy and detection rates for this species as species detection may be low and inhabit other suitable wetlands on the landscape. Through standardized surveys, more effort is needed to refine species habitat requirements. The effects of climate change on ringed boghaunter and climate resistance of its aquatic habitat, including water temperature and water quantity, warrant further investigation. Furthermore, confirmation of known and identification of source and sink wetlands are needed to accurately assess the species risk to anthropogenic threats.

References

Dunkle, S.W. 2000. Dragonflies Through Binoculars. Oxford University Press.

Charlton, R.E. 1985. A colony of Williamsonia fletcheri discovered in Massachusetts. Ent. News 96:201-204.

Charlton, R.E., and R.A. Cannings. 1993. The larva of Williamsonia fletcheri. Odonatologica 22:335-343.

Lam, E. Dragonflies of North America. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2024.

Needham, J.G., M.J. Westfall, Jr., and M.L. May. 2000. Dragonflies of North America. Scientific Publishers.

Nikula, B., J.L. Ryan, and M.R. Burne. 2007. A Field Guide to the Dragonflies and Damselflies of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program.

Paulson, D. Dragonflies and Damselflies of the East. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Soltesz, K. 1996. Identification Keys to Northeastern Anisoptera Larvae. Center for Conservation and Biodiversity, University of Connecticut.

Tennessen, K. Dragonfly Nymphs of North America: An identification guide. Springer, 2019.

Walker, E.M., and P.S. Corbet. 1975. The Odonata of Canada and Alaska, Volume III. University of Toronto Press.

Contact

| Date published: | April 10, 2025 |

|---|