Overview

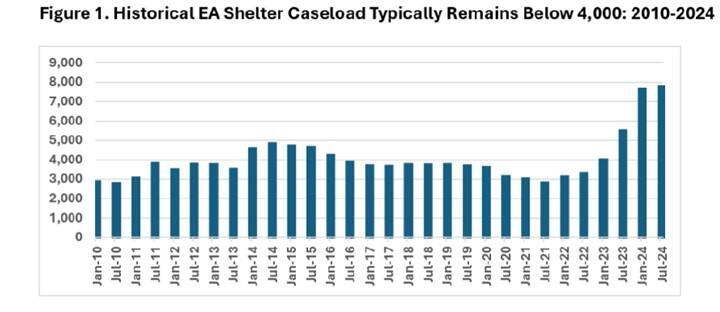

The Executive Office of Housing and Livable Communities (EOHLC) failed to adequately assess and act upon the increased demand for service, resulting in improper and unlawful emergency procurements for food and transportation. Data provided to us by EOHLC indicated a trend in increased emergency shelter needs starting in December 2022. Naturally, an increased demand in emergency shelter needs would also result in an increased demand for food and transportation services to support the families using the emergency shelters. The data that EOHLC provided to us, and that we reviewed, reflects that EOHLC did not adequately plan for this increasing demand for food and transportation services. The demand for emergency shelter had already surpassed the baseline capacity of 3,600 units by January 2023. The situation continued to worsen throughout the remainder of 2023. EOHLC should have used the normal procurement process sometime between January 2023 and August 2023 to address the need for additional food and transportation services but instead delayed until August 2023, when it issued emergency, no-bid contracts. This would have allowed for competition among vendors with improved pricing, terms, and fairness. Similarly, the extension terms of the emergency contracts were not justified. Emergency contracting is designed to “buy time” to conduct a fair, legitimate procurement process under normal procurement rules. This did not occur.

It is clear that state agencies may enter into emergency contracts in certain circumstances. The question is whether the circumstances surrounding the food and transportation procurements amount to an unforeseen emergency and whether the lengths of the contracts that flowed from the emergency situation were appropriate. We believe that EOHLC could have better foreseen the increased demand for food and transportation services based upon data it was tracking and made use of the normal procurement process instead.

It may be the case that EOHLC did not procure these services earlier because it did not know how many families it would ultimately need to serve. We note here that the Commonwealth and cities and towns often procure goods and services in anticipation of unknown service needs. Some municipalities procure emergency trades services to handle pipes bursting in the winter at school buildings, emergency roof repairs, and other needs. At the time of these procurements, it is not known that these services will be needed, or to what extent and how often they will be needed. These services are procured because the need is possible and can reasonably be foreseen. So, too, could the Commonwealth have procured food and transportation services for a growing number of people on a nonemergency basis through sound planning and procurement management.

EOHLC entered into no-bid emergency contracts with Spinelli for food services and Mercedes Cab Company / Pilgrim Transit for transportation services. The demand for emergency shelter had already surpassed the baseline capacity of 3,600 units by January 2023. The graph below, which EOHLC included in its justification package for its use of emergency procurement procedures, illustrates this upward trend, showing that the increased demand for emergency shelter, and by extension for food and transportation services, was not only foreseeable, it was also well-known. Despite this, EOHLC provided us no valid justification for the no-bid emergency contracts. The situation was not unexpected, and the need for food and transportation services had been predictable well before the emergency procurement was initiated.

Source: The emergency contract between EOHLC and Mercedes Cab Company, dated October 17, 2023.

Costs of No-bid Emergency Contracts

The $10 million procurement with Spinelli was contracted for eight months, a duration that was inordinately long and inconsistent with best practices for an emergency contract, see the “Authoritative Guidance” section below. Similarly, the $2.8 million procurement with Mercedes Cab Company / Pilgrim Transit was initially set for October 13, 2023, through April 13, 2024, but was amended on February 9, 2024, for an additional $1.0 million. Later, this contract was further amended for another $3.0 million and extended until June 30, 2024. This, too, is inconsistent with law, regulation, and best practices for emergency procurements, contracts, contract amendments, and public transparency.

Emergency contracts are intended to address immediate needs and are expected to have limited durations that allow the Commonwealth to secure emergency services while providing time to secure more permanent services under legally and appropriately procured contracts, but no more. Said another way, the purpose of an emergency contract is to meet an immediate need and “buy time” for a genuine, legal, competitive procurement to take place. An emergency contract is not intended to permit the Commonwealth to waive procurement rules to award long-term no-bid contracts to vendors.

EOHLC could have, at the least, entered into short-term contracts with vendors while it examined the need for long-term services.

By using emergency contracts for such an extended period, EOHLC bypassed established procurement procedures, which resulted in a lack of competitive bidding, transparency, and accountability in the contracting process. Additionally, the excessive duration of the contracts resulted in inefficiencies and unnecessary costs, as the emergency situation could have been addressed through alternative means. This noncompliance with procurement guidelines undermines the integrity of the procurement process and resulted in an inefficient use of public funds. It also undermines the public’s faith in its government.

Authoritative Guidance

Emergency procurements by the Commonwealth, including no-bid procurement, are authorized by Section 22 of Chapter 7 of the Massachusetts General Laws and are governed by Section 21.05 of Title 801 of the Code of Massachusetts Regulations (CMR). These procurements are intended to be rare and should be specific to a true emergency as described below.

According to 801 CMR 21.05(3),

An emergency Contract shall be appropriate whenever a Procuring Department Head determines that an unforeseen crisis or incident has arisen which requires or mandates the immediate acquisition of Commodities or Services, or both, to avoid substantial harm to the functioning of government or the provisions of necessary or mandated services or whenever the health, welfare, or safety of Clients or other persons or serious damage to property is threatened.

The Office of Inspector General’s The Chapter 30B Manual: Procuring Supplies, Services and Real Property states,

If the time required to comply fully with Chapter 30B would endanger the health or safety of people or their property due to an unforeseen emergency, you may procure the needed item or service without complying with all of Chapter 30B’s requirements. Even under emergency circumstances, however, you must comply with Chapter 30B to the extent possible. For example, if you do not have time to advertise for two weeks, you can shorten the advertising period; or, if you have no time to advertise, you can solicit quotes. You may procure only those supplies or services necessary to meet the emergency.

You must maintain a record of each emergency procurement, documenting the basis for determining that an emergency exists, the name of the vendor, the amount and type of contract, and a list of the supplies or services purchased under each contract. We recommend that you also include in your record all procedures followed to elicit competition. Your record of an emergency procurement must be submitted as soon as possible to the Goods and Services Bulletin for publication.

These regulations should serve as a best practice, at a minimum, even if they were to have been waived by the Governor’s August 8, 2023 letter (see Appendix B). The Governor’s letter, however, does not explicitly waive procurement law or 801 CMR 21.05, as required by Section 8 of Chapter 639 of the Acts of 1950, which states the following:

The governor may exercise any power, authority or discretion conferred on him by any provision of this act, either under actual proclamation of a state of emergency as provided in section five or in reasonable anticipation thereof and preparation therefor by the issuance or promulgation of executive orders or general regulations, or by instructions to such person or such department or agency of the commonwealth, including the Massachusetts Emergency Management Agency, or of any political subdivision thereof, as he may direct by a writing signed by the governor and filed in the office of the state secretary (emphasis added). Any department, agency or person so directed shall act in conformity with any regulations prescribed by the governor for its or his conduct.

We note that the Office of the Inspector General has long provided guidance for cities and towns on their use of emergency procurements in its guide, The Chapter 30B Manual: Procuring Supplies, Services and Real Property. While not directly applicable to this procurement, we consider it a best practice to help ensure an ethical, legal, and appropriate use of emergency contracts.

As a best practice to the maximum extent possible, departments should shop around for competitive prices for emergency procurements to ensure the best price and best contract terms and to permit multiple vendors to participate in the process. Also, departments should only enter into emergency no-bid contracts for the period necessary to alleviate the immediate risk of harm, damage, or danger with longer term procurements replacing these emergency contracts at the earliest possible time.

Reasons for Noncompliance

EOHLC did not adequately assess or act upon the known (and therefore foreseeable) increasing demand for food and transportation services. The procurement team did not sufficiently demonstrate that the use of no-bid emergency contracts was warranted, nor did it justify the excessive duration of the contracts, despite the known trends and data indicating the surge in demand.

Recommendations

- In cases where increasing demand or foreseeable circumstances are identified, EOHLC should use appropriate procurement processes, such as competitive bidding, to ensure transparency, fairness, and cost-effectiveness.

- EOHLC should review and adjust its procurement practices to ensure that it complies with Section 22 of Chapter 7 of the General Laws and regulations for emergency contracts, ensuring that all emergency contracts are justified based on unforeseeable events. Emergency contracts should be replaced by properly procured contracts as soon as practicable.

- EOHLC should limit emergency contracts to no longer than a period of time required to conduct the appropriate procurement processes, including competitive bidding, to ensure transparency, fairness, and cost-effectiveness. In most cases, we would expect emergency contracts to last weeks, not several months.

- EOHLC should ensure that, before not complying with Section 22 of Chapter 7 of the General Laws, the orders to do so are legal and valid under Chapter 639 of the Acts of 1950.

Auditee’s Response

EOHLC cannot concur with and rejects Audit Finding 1 as fundamentally wrong and unfounded.

There is no question that the Commonwealth has been confronted by an unprecedented crisis. The [Office of the State Auditor (SAO)] itself has used the words “crisis” and “incredibly challenging time” to describe the situation we have faced. The emergency procurements conducted were proper, lawful, and effective during this period of emergency.

The SAO’s suggestion that its own performance auditors could have predicted a once in a lifetime surge in shelter demand—when shelter system operators throughout the country did not—is surprising to say the least. EOHLC strongly rejects the suggestion that it should have foreseen what was, in fact, a historically unprecedented increase in demand for [Emergency Assistance (EA)] shelter services driven by international and national forces far beyond EOHLC’s control.

In large part, the SAO’s report relies on a narrow slice of data covering the years 2021 to 2023 to suggest that the dramatic rise in demand was a predictable trend. While demand has fluctuated over time, it has never risen at a rate, or to a level, that it experienced beginning in 2023:

In fact, 2023 was not the first time that the EA system had experienced a rise in demand. In November 2014, for example, the EA system expanded to serve 4,825 families, a record at the time. But prior increases in demand had never continued or increased at the level seen in 2023, and EOHLC could not have predicted the national and international causes. EOHLC took an appropriately measured response to the initial rise in demand. It worked with contracted shelter service providers through existing contracts, a rolling [request for response (RFR)], and newly procured vendors to expand the shelter system, as had happened in the past.

But demand did not moderate and was further compounded by the low exit rates, data not requested or considered by the SAO. By August 2023, the EA caseload had surpassed its 2014 record, and it was clear that the system was facing an unprecedented rise in demand for shelter. On August 8, 2023, the Governor declared a State of Emergency due to the rapid and unabating increase in the number of families with children and pregnant people seeking shelter. The Governor also worked cooperatively with the Legislature to implement much needed reforms. The result has been a much more efficient and much more effective shelter system, capable of meeting the most pressing needs of Massachusetts families experiencing homelessness.

EOHLC also rejects the assertion that the emergency procurements were improper or unlawful. The emergency procurements put in place as demand spiked addressed critical unmet needs for food and transportation for families and children. As the demand for shelter grew, EOHLC maintained an open procurement for EA shelter services. But longstanding providers began to run out of the ability not only to provide physical shelter but also to meet urgent needs for food and transportation. Further, the number of new vendors bidding for this open procurement for shelter services, which included food and transportation, was limited. EOHLC, bound by its statutory obligation to provide shelter and associated services to eligible families, had to find a solution. For a limited period during the peak of the emergency, EOHLC placed families in hotels without immediate shelter service providers.2 In many cases, these hotels could not provide access to refrigeration or cooking facilities. EOHLC did not have direct contracts for food, so it had to move quickly to secure food services. Specifically, on September 25, 2023, EOHLC executed an emergency contract with Spinelli’s. Spinelli’s was an existing Massachusetts Emergency Management Agency (“MEMA”) contractor that had provided much needed services to the Commonwealth during the COVID crisis under the prior administration. Spinelli’s was uniquely qualified and capable of addressing immediate and constantly fluctuating needs at frequently varying locations.3 EOHLC executed the contract with Spinelli’s on an emergency basis because allowing hundreds of families and children sheltered in hotels to go without access to food was rightly determined to be an unacceptable alternative.4 Instead of utilizing this procurement tool given to agencies, the alternative choice for EOHLC would have been to ignore the health and safety needs of the families and wait at least 5 to 6 months to competitively procure food and transportation services. By doing so, EOHLC would have risked not only the health and safety of those families, but violated its obligation to provide shelter and associated services to these families. It is important to note that EOHLC immediately initiated a procurement process and phased out these emergency contracts as EA shelter providers were brought on to serve all hotel sites. Today, no direct food contracts remain in place.

The SAO report notes that “EOHLC should have entered into short-term emergency contracts with vendors while [it] examined the need for long-term services.” EOHLC did just that. On the day the Spinelli’s emergency contract was executed, EOHLC initiated a procurement process for food services on COMMBUYS. The procured contracts included several food vendors, including Spinelli’s, and were signed in early spring 2024. The Spinelli’s emergency contract ended in March 2024. EOHLC also attempted to competitively procure for transportation services following the execution of our emergency contract with Mercedes Cab Company / Pilgrim Transit (MCC), but received no satisfactory bidders. Further information on this contract can be found in our response to Audit Finding 5.

EOHLC does not turn to emergency procurements lightly. But each day that food or shelter services were delayed would have risked leaving children and families without food or safe housing. EOHLC is confident that it was appropriate and lawful to utilize emergency procurements under these circumstances. Nonetheless, EOHLC fully supports the use of competitive procurements and of emergency contracts only for the time necessary to respond to the emergency, and the importance of transparency and accountability in the contracting process. That is what occurred here.

[. . .]

2. EOHLC also procured additional shelter service providers during the winter of 2023–2024.

3. EOHLC provided the SAO with email correspondence specific to the decision to why Spinelli’s was selected. EOHLC believes it is important to consider the information contained in the correspondence. EOHLC did explore existing statewide contracts. The statewide contract available was limited to unprepared foods, which was not suitable as many locations had no kitchens. The email correspondence also provides the names of three vendors shared with EOHLC from MEMA, which were all considered prior to the selection.

4. EOHLC estimates the typical procurement process to be five to six months.

Auditor’s Reply

We stand by the work performed and the information presented in the finding. EOHLC indicates in its response that it could not have foreseen the increased demand in emergency shelter services, despite providing data that shows that the number of shelter caseloads in January 2023 was higher than in any period since January 2016, and that those caseloads only continued to grow. We found that EOHLC could have anticipated the increased demand in food and transportation services as a result of the increased demand in emergency shelters, which we believe could have been predicted, given the data EOHLC was tracking. It is logical to recognize that food and transportation services would be required with the increased demand for emergency shelters. Given that the caseloads number in January 2023 was already higher than at any point in the prior seven years, it seems fair to conclude that the Commonwealth could, in January 2023 at the very least, have begun anticipating the need for additional food and transportation services that were ultimately required later in 2023. We certainly do not expect them to have predicted the magnitude of the need with accuracy, but we believe it would have been appropriate to begin planning for contingencies—including significant continued increases in caseloads and the potential that these increases outstripped the availability of existing housing, food, and transportation providers.

Given that in January 2023, the number of caseloads were higher than in any period in the prior seven years, it also seems fair to conclude that EOHLC could have used the normal procurement process earlier than it did and before it decided to engage in emergency no-bid contracts with Spinelli and Mercedes Cab Company / Pilgrim Transit. Instead, EOHLC did not take action until after a state of emergency was declared by Governor Healey in August 2023, roughly seven months later, at which time EOHLC chose to use emergency no-bid contracts to address the need for food and transportation services. We believe that, given EOHLC’s own data, which it provided in its response, EOHLC could have acted sooner to procure food and transportation services to address the increased and increasing demand using the normal, competitive procurement process, reducing or eliminating the need for emergency no-bid contracts.

As we indicate in other findings in this report, EOHLC did not maintain all of the documents necessary to constitute sufficient procurement files, required by law, regarding these emergency no-bid procurements. In its response, EOHLC points out that it did use the normal procurement process for food services. This is accurate. However, EOHLC issued a request for response (RFR) on September 25, 2023, the same day it signed the emergency no-bid contract with Spinelli. By entering into the emergency no-bid contract with Spinelli, EOHLC committed to an eight-month contract (the terms of the contract covered August 1, 2023 through March 31, 2024) with this vendor. EOHLC did issue a regular procurement, but this procurement could not be in force or effect until after the expiration of the emergency no-bid contract. There could be no competitively procured contract until April 1, 2024 at the earliest. Therefore, for all of the reasons stated above, we believe these emergency contracts were improper and unlawful, as the need for these services was not unforeseen or unforeseeable, based on the information we had been provided.

We strongly encourage EOHLC to implement our recommendations regarding this matter. As part of our post-audit review process, we will follow up on this matter in approximately six months.

| Date published: | May 20, 2025 |

|---|