- Scientific name: Balaenoptera physalus

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

- Endangered (US Endangered Species Act)

Description

Fin whales can weigh between 36-73 metric tons (40-80 tons) and measure 23-26 m (75-85 ft) in length, second in size only to the blue whale (NOAA 2025). Fin whales have a sleek, streamlined body with a pointed head and are dark grey to brown on top, with white underneath. They have a tall, hooked dorsal fin located two-thirds of the way down their body. Fin whales are commonly called ‘razorbacks’ for the ridges on the middle of the back behind the dorsal fin. On the right side, the lower jaw is white, which is a unique asymmetrical coloration for distinguishing this species from all other baleen whales. Similarly, the 260-480 baleen plates in the front half of the mouth are also white with darker plates in the back half of the mouth. By contrast, the lower left jaw is gray and all baleen plates on the left side are dark. This coloration may aid in herding fish during feeding, although its primary purpose is unknown.

Life cycle and behavior

Fin whales are often found alone or in groups of 2-7 individuals but can be part of larger aggregations, including with different whale species, when feeding (NOAA 2025). Feeding occurs largely in summer as they target small fish and krill. Fin whales can eat up to 1.8 metric tons (2 tons) of food each day. They fast while migrating in winter. Fin whales seen off the coast of Massachusetts may not have a winter breeding ground in common (Ramp et al. 2024).

Though little is known about the social and mating systems of fin whales, similar to other baleen whales, long-term bonds between individuals appear to be rare. Fin whales can live between 80 and 90 years. Males reach sexual maturity at 6-10 years of age, while females are sexually mature between 7-12 years old. The gestation period is 11-12 months. Newborns are approximately 5.5 m (18 ft) long and can weigh up to 2.7 metric tons (6000 lbs). Blue whales and fin whales will sometime mate producing hybrid offspring. Fin whales produce unique sounds at the very low frequency of 20 Hz. These sounds are likely used for communication.

Population status

The fin whale is classified as Endangered under both the Massachusetts and federal Endangered Species Acts. However, in response to globally increasing numbers, the fin whale was moved from Endangered to Vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List of Threatened Species in 2018. Locally, fin whale numbers were significantly reduced by commercial whaling, including whales killed in the late 1800s as they followed schools of sand lance and herring into Cape Cod Bay and even Provincetown Harbor (Reeves et al. 2002). Fin whales have not been hunted in the Gulf of Maine since commercial whaling was prohibited in US waters in 1972.

Distribution and abundance

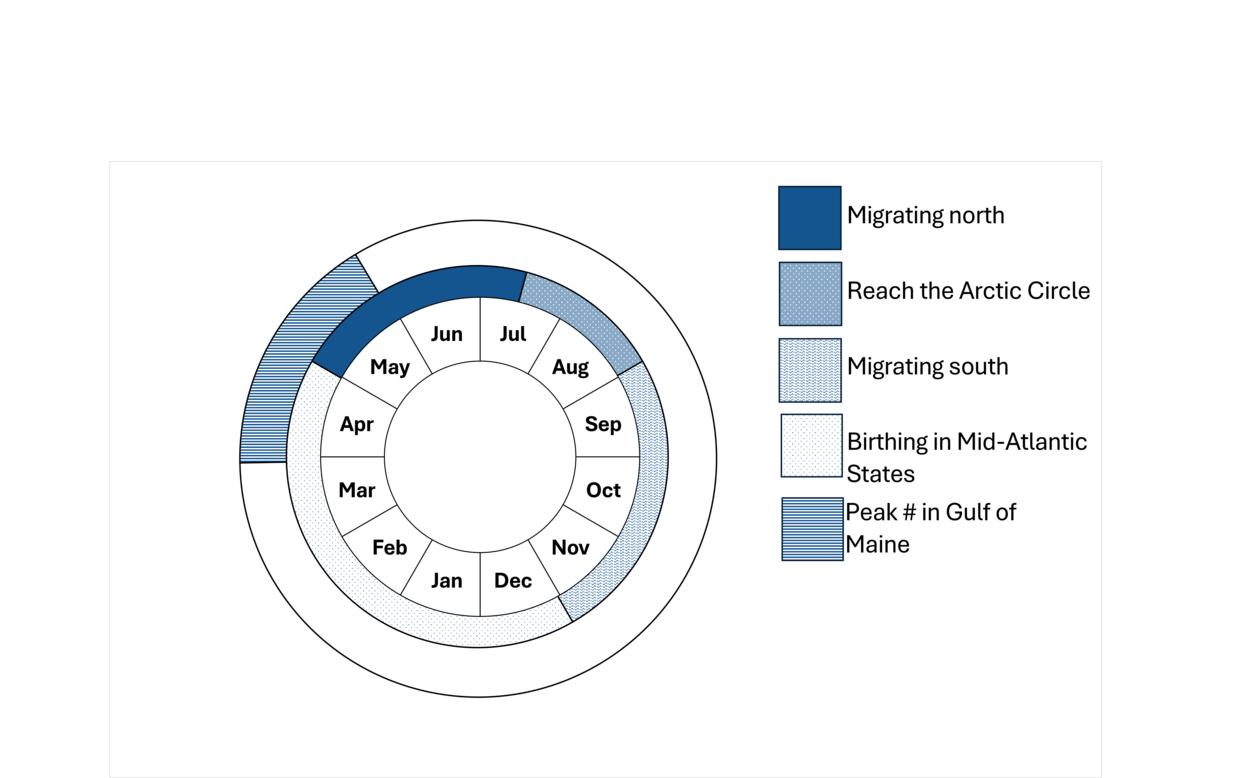

Fin whales prefer deep, offshore waters of all the major oceans, primarily in temperate and polar latitudes. There are two named subspecies of fin whales, including B. physalus physalus, in the northern hemisphere, and B. physalus quoyi, in the southern hemisphere. Fin whales are migratory with a complex migration pattern, moving seasonally to high-latitude feeding areas. Fin whales in the North Atlantic and North Pacific have been divided into four stocks in US waters: Hawaii; California/Oregon/Washington; Alaska (Northeast Pacific); and Western North Atlantic.

Fin whales occur from the Greater Antilles, north to the Arctic Ocean. They can be found in the Gulf of Maine year-round and in relatively large numbers in summer and fall. Over the last two decades (1998-2018), fin whales appear to have shifted the timing of peak habitat use in Cape Cod Bay earlier by 5.8 days, although this trend is not statistically significant (Pendleton et al. 2022 in Staudinger et al. 2024). This shift in timing was positively associated with the earlier onset of spring in Gulf of Maine waters. In contrast, for 1984-2010, fin whales arrived a total of 28 days earlier, or a little over 1 day/year earlier, in the Gulf of St. Lawrence; this shift in phenology coincided with changes in ice-free weeks and sea-surface temperatures in the region (Ramp et al. 2015). Fin whales also left the Gulf of St. Lawrence 11 days earlier from 1984 – 2010, resulting in longer residence times in the Gulf of St. Lawrence overall (Ramp et al. 2015).

Approximate range of the fin whale (NOAA Fisheries)

Habitat

Fin whales can be found in the Gulf of Maine year-round.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Major threats to fin whales are vessel strikes, fishing gear entanglement, ocean noise, and climate change (NOAA 2025). This species is highly vulnerable to vessel strikes and the risk of injury or mortality from vessel strikes is only increasing as polar ice melts due to climate change and result in increased ship traffic in polar routes. Fin whales can become entangled in a variety of fishing gear and may swim long distances while entangled. This can result in fatigue, severe injury, and reduced feeding ability which can lead to reduced reproductive success and mortality. Ocean noise can disrupt normal behaviors including migration. Ocean noise has been linked to the stranding of some whale species (NOAA 2025). Climate change is changing the distribution of prey, altering oceanic conditions, and decreasing ice cover. These impacts can stress whales and result in less successful feeding and reproduction (NOAA 2025).

Conservation

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration finalized a recovery plan for fin whales in 2010. The document makes the following major recommendations in order to down-list fin whales from Endangered to Threatened:

- Reduce or eliminate injury or death caused by ship collision,

- Reduce or eliminate injury or death caused by fisheries and fishing gear,

- Protect habitats essential to the survival and recovery of the species,

- Minimize effects of vessel disturbance,

- Continue the international ban on hunting and other directed take,

- Monitor the population size and trends in abundance of the species, and

- Maximize efforts to free entangled or stranded fin whales and get scientific information from dead specimens.

All stranded whales in Massachusetts should be reported immediately to the IFAW Marine Mammal Rescue and Research on Cape Cod 508-743-9548 or the Northeast Marine Mammal Center at 866-755-6622.

References

National Marine Fisheries Service. 2010. Recovery plan for the fin whale (Balaenoptera physalus). National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, MD. 121 pp.

National Marine Fisheries Service. 2010. Fin Whale (Balaenoptera physalus) 5-year Review: Summary and Evaluation. National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, MD. 40 pp. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/s3//dam-migration/508_compliant_final_feb_2019_finwhale_5-year_review.pdf

NOAA [National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration]. 2025. Species Directory: Fin Whale. Available at: Fin Whale | NOAA Fisheries. Accessed on 7/4/25.

Ramp C, V Lesage, A Ollier, M Auger-Methe, R Sears. 2024. Migratory movements of fin whales from the Gulf of St. Lawrence challenge our understanding of the Northwest Atlantic stock structure. Scientific Reports 14(11472).

Reeves R, T Smith, RL Webb, J Robbins, PJ Clapham. 2002. Humpback and fin whaling in the Gulf of Maine from 1800 to 1918. Marine Fisheries Review 64:1-12.

Staudinger, MD, AV Karmalkar, K Terwilliger, K Burgio, A Lubeck, H Higgins, T Rice, TL Morelli, A D'Amato. 2024. A regional synthesis of climate data to inform the 2025 State Wildlife Action Plans in the Northeast U.S. DOI Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center Cooperator Report. 406 p. https://doi.org/10.21429/t352-9q86.

Contact

| Date published: | August 18, 2025 |

|---|