- Scientific name: Vermivora chrysoptera

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Golden-winged warbler (Vermivora chrysoptera)

The golden-winged warbler is a beautiful bird, about 11 cm (4.5 in) in length, with a distinctive combination of colors and patterns. The male has a white underside and a gray back, with bright yellow patches on the crown (forehead) and upper wing surfaces, and a black throat and bill. A black “mask” extends across the eyes, with patches of white above and below the mask. The female golden-winged warbler is similar in appearance, but the colors are considerably duller. Male golden-winged warblers sing most persistently in the morning early in the nesting season. Golden-wings make use of two types of songs. One of the songs is characterized by a high-pitched buzzy phrase followed by 1 to 6 shorter buzzy phrases and is used to attract mates. The other song consists of 3 to 5 low buzzy phrases ending with a higher buzzy phrase and is used to defend the bird’s territory against other males.

The blue-winged warbler is a very close relative of the golden-winged warbler, but its body is predominantly yellow instead of gray and white. The courtship calls and displays of each species are very similar. As a result, golden-winged warblers often mate with blue-winged warblers, creating hybrids. One of these hybrids is known as Brewster’s warbler. It is very similar in appearance to the golden-winged warbler but has a yellow patch on its chest and lacks black throat color; its mask is also less conspicuous. Another hybrid, known as Lawrence’s warbler, has a yellowish head and underside, black throat and mask, and two white wingbars.

Life cycle and behavior

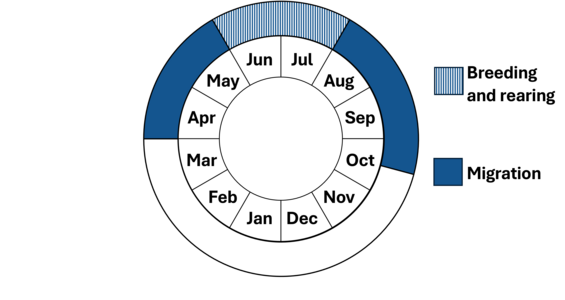

Phenology in Massachusetts. This is a simplification of the annual life cycle. Timing exhibited by individuals in a population varies, so adjacent life stages generally overlap each other at their starts and ends.

Golden-winged warblers usually arrive in New England in early May, the females arriving a day or two later than the males. The males immediately set up territories and sing to defend their territory and attract females. Males often return to the same site year after year. Following pairing, the females build bulky nests on or near the ground. The nest is constructed out of grasses, leaves, vine tendrils, and other fine materials, and is supported by bushes, or very frequently, by goldenrod stems. From mid-May to mid-June, three to seven creamy white eggs with brown speckles are laid, one egg per day. The eggs are incubated by the female for 10 to 11 days. Both parents feed and care for the nestlings. Although the chicks are able to leave the nest ten days after hatching, the parents continue to care for them for several weeks. Golden-winged warblers begin their southward migration in late August or early September.

The golden-winged warbler’s feeding behavior resembles that of chickadees: it hops from twig to twig, sometimes hanging upside down, while peering around the branches for insects. They feed on larvae, small bugs, spiders, ants, beetles, and caterpillars (including gypsy moth caterpillars). The life span of the golden-winged warbler is about 2 to 5 years.

Population status

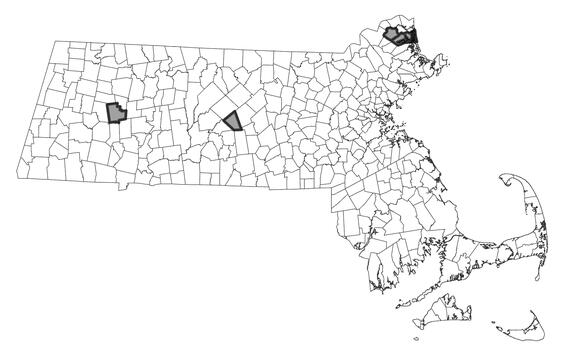

According to the Breeding Bird Survey, the Northeast population of the golden-winged warbler has declined dramatically between 1966-2022. The species is categorized as near threatened by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN). The golden-winged warbler is listed as an endangered species in Massachusetts due to its rapidly decreasing population; in fact, there is no longer a viable population anywhere in Massachusetts.

Distribution and abundance

In the 19th century, golden-winged warblers were rarely seen in New England, but by the early 1900s, their population in New England increased as many farmlands were abandoned. Golden-winged warblers remained locally common until around 1940, and blue-winged warblers were not present in the state at that time. Since then, blue-winged warblers increased steadily in numbers throughout the state and have become common in many areas. With increasing numbers of blue-winged warblers, the golden-winged warbler rapidly declined and is now thought to be extirpated as a nesting bird in Massachusetts. However, blue-winged warblers also seem to be declining after reaching a zenith in the early 1980s.

The summer range of the golden-winged warbler currently extends from Vermont west to Minnesota and very locally south down the Appalachian Mountains. During the early part of the century, the golden-winged warbler’s summer range expanded northward and eastward but has since disappeared from the southern extent of its range. The winter range of the golden-winged warbler extends from southern Mexico to Venezuela and Colombia.

Distribution in Massachusetts. 1999-2024. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Golden-winged warblers prefer woodland edges bordering early successional clearings (such as abandoned farmland and powerline areas), heavily overgrown with patches of grass, weeds, bushes, shrubs, briars, and small trees. Common plant species found in these habitats are grapevine (Vitis spp.), goldenrod (Solidago spp.), and birch (Betula spp.). Habitat that best supports golden-winged warblers, but not blue-winged warblers, include young forest habitat within extensive forested landscapes and often associated with wetlands.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Golden-winged warbler (Vermivora chrysoptera)

Threats

The biggest threat to golden-winged warbler populations is hybridization and interspecific competition with the blue-winged warbler. Cowbird parasitism and loss or degradation of wintering habitat also may be contributing factors to the golden-winged warbler population decline. However, the amount of suitable habitat for the species does not seem to be a limiting factor; there is plenty of habitat available, but no birds to occupy it.

An additional threat to the species is collisions with buildings and other structures, as approximately 1 billion birds in the United States are estimated to die annually from building collisions. A high percentage of these collisions occur during the migratory periods when birds fly long distances between their wintering and breeding grounds. Light pollution exacerbates this threat for nocturnal migrants as it can disrupt their navigational capabilities and lure them into urban areas, increasing the risk of collisions or exhaustion from circling lit structures or areas.

Conservation

In regions where the golden-winged warbler persists, creation of suitable nesting habitat in areas without blue-winged warblers is important for population persistence. Additionally, land protection efforts on the wintering ground will support full annual cycle conservation efforts for the species.

Bird collision mortalities can be minimized by making glass more visible to birds. This includes using bird-safe glass in new construction and retrofitting existing glass (e.g., screens, window decals) to make it bird-friendly and reducing artificial lighting around buildings (e.g., Lights Out Programs, utilizing down shielding lights) that attract birds during their nocturnal migration.

References

Confer, J. L., P. Hartman, and A. Roth (2020). Golden-winged Warbler (Vermivora chrysoptera), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Sauer, J.R., J.E. Hines, J.E. Fallon, K.L. Pardieck, D.J. Ziolkowski, Jr., and W.A. Link. 2022. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 - 2022. Version 01.30.2015 USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, Laurel, MD.

Contact

| Date published: | April 25, 2025 |

|---|