- Scientific name: Ammodramus savannarum

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Threatened (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Grasshopper sparrow

The grasshopper sparrow is a small sparrow of sandplain grasslands. It is 11-13 cm (4.5 to 5.5 in) long with a narrow short tail. Each feather of the tail tapers to a point giving it a ragged appearance. It has a flat head which slopes directly into the bill. The dark brown crown is divided by a thin cream-colored center stripe. A yellowish spot extends from the bill in front and below the eye. The sexes are similar. The typical song, often mistaken for the song of a grasshopper, consists of two chip notes followed by “tsk tsick tsurrrr.” Breeding birds also sing a complicated song with many squeaky and buzzy notes intermixed in a long phrase.

Life cycle and behavior

Grasshopper sparrows eat, sleep and nest on the ground. When flushed, they usually flutter low for a short distance and drop back into the grass. On the ground grasshopper sparrows typically hop or run. They are largely insectivorous, and patches of bare ground are critical to their foraging behavior. Grasshoppers are a primary food item, and they also feed on spiders, myriapods, snails and small seeds.

Grasshopper sparrows arrive in Massachusetts in late May. The male then establishes a 1-4-acre territory by repeatedly singing along the edges of this territory and defending the area from competing males. Pairs produce one brood each summer. The well-hidden nests are domed structures of grasses built at the base of clumps of grass. Only the female incubates the eggs (typically 3-5), which take 12 days to hatch. The young, which are wholly dependent on the female at hatching, leave the nest after 9 days and follow the parent on the ground until they fledge. If found on the nest, the female flutters through the grass, feigning lameness. Though the male does not directly care for the young, it does react to predators near the nest. Nests may be parasitized by cowbirds. Breeding activity diminishes by mid-August after which the families disperse.

By mid-September grasshopper sparrows migrate to their wintering grounds from the southern United States coastal plain through to Central America and the West Indies.

Population status

The grasshopper sparrow is classified as a Threatened species in Massachusetts, where it is known to nest at fewer than 20 sites. Many of the current locations are in fields adjacent to airfields. This sparrow formerly was abundant on Nantucket, Martha’s Vineyard, and in eastern Massachusetts. Loss of appropriate habitat to land development, changes in agricultural practices (early harvesting and fewer fallow fields), and natural succession (abandoned fields growing up to shrubs and woods) appears to be the primary factor in its decline. Openings created by forest fires once provided habitat but these are now rare.

Distribution and abundance

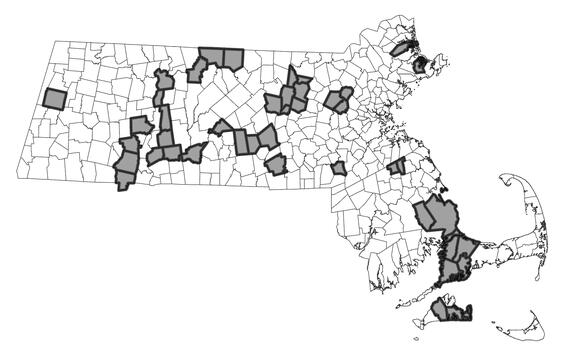

Grasshopper sparrow is listed as a Threatened species in Massachusetts. They were formerly somewhat common on the Massachusetts coastal plain and interior valleys, but loss of appropriate habitat to land development and succession of open fields is a primary factor in its decline.

Distribution in Massachusetts. 1999-2024. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Grasshopper sparrows nest primarily in sandplain grassland natural communities. Currently, many active breeding sites in Massachusetts are associated with airfields. Nesting habitat typically features large patches with high interior-to-edge ratios dominated by warm season bunch grasses (particularly little bluestem [Schizachyrium scoparium]) with interstitial areas of bare mineral soil and limited woody vegetation.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Grasshopper sparrow

Threats

The large expanses of sandplain grassland habitat needed by breeding grasshopper sparrows is now very rare, and therefore, breeding occurrences of grasshopper sparrows have become very rare. The primary threat to grasshopper sparrow populations in Massachusetts is now habitat loss in the remaining breeding areas. Habitat loss occurs in two primary ways: direct habitat loss due to development, and indirect habitat loss due to the succession of sandplain grassland habitat to woody and generalist vegetation. Sandplain grasslands are a highly disturbance-dependent habitat, meaning that they need to experience regular appropriate disturbance events to maintain their integrity. Historically, this disturbance was often regularly occurring fire on the landscape. In the absence of fire, sandplain grassland will often shift to other unsuitable habitat types, such as grasslands dominated by turf grasses, meadows of clonal asters and goldenrods, shrublands or young forests. In situations where the habitat is maintained by regular mowing (like on airfields), mowing during the breeding often results in the destruction of breeding attempts.

Predation by domestic cats has been identified as the largest source of mortality for wild birds in the United States with the number of estimated mortalities exceeding 2 billion annually. Cats are especially a threat to those species that nest on or near the ground.

An additional threat to the species is collisions with buildings and other structures, as approximately 1 billion birds in the United States are estimated to die annually from building collisions. A high percentage of these collisions occur during the migratory periods when birds fly long distances between their wintering and breeding grounds. Light pollution exacerbates this threat for nocturnal migrants as it can disrupt their navigational capabilities and lure them into urban areas, increasing the risk of collisions or exhaustion from circling lit structures or areas.

Conservation

Grasshopper sparrows are very resilient and respond well to active habitat restoration and management. Sandplain grassland habitat that has been degraded due to a lack of management can often be restored by controlling generalist vegetation, overseeding to little bluestem, and introducing a management regime that ideally includes prescribed fire. Grasshopper sparrows are excellent pioneers and will quickly find and recolonize restored habits. In situations where grasshopper sparrows are present and prescribed fire is not currently feasible, mowing regimes should be adjusted to avoid the breeding season. However, dormant season mowing is generally not enough to prevent the eventual shift of sandplain grassland habitat to more generalist (and unsuitable) habitat, and so a more integrated management will be needed over the long-term.

Promote responsible pet ownership that supports wildlife and pet health by keeping cats indoors and encouraging others to follow guidelines found at fishwildlife.org.

Bird collision mortalities can be minimized by making glass more visible to birds. This includes using bird-safe glass in new construction and retrofitting existing glass (e.g., screens, window decals) to make it bird-friendly and reducing artificial lighting around buildings (e.g., Lights Out Programs, utilizing down shielding lights) that attract birds during their nocturnal migration.

Contact

| Date published: | April 2, 2025 |

|---|