The number of people experiencing homelessness in the United States has been steadily rising in recent years. The recently released 2024 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (AHAR) from HUD showed the highest total number of persons experiencing homelessness in the US since survey efforts began. Nationally there was an 18.1% increase relative to persons identified in 2023[i]. Massachusetts saw an even more startling increase in persons experiencing homelessness with AHAR reporting a 54% increase in total persons experiencing homelessness in Massachusetts—the third largest increase among all states and the 5th largest homeless population. Rising housing costs and lack of affordable housing are national trends widely recognized as the leading causes of increasing homelessness. A 2019 study commissioned by HUD identified rising rents and housing overcrowding as key predictors for homelessness. That study found that, without other interventions, a 10% increase in average rent results in nearly 2 additional people (1.92) out of every 10,000 adults becoming homeless. The impact of overcrowding was even more powerful—when overcrowded housing units (defined as more than 1.5 people per room) increased by just 1%, more than 5 additional people (5.44) per 10,000 end up experiencing homelessness.

Doubling up is also a common precursor to HUD-defined homelessness—a recent statewide study of people experiencing homelessness in California found that nearly half (49%) had entered homelessness from a “non-leaseholder, non-institutional setting,” compared to 32% who had been leaseholders and 19% who had been in institutional settings. The median notice period for non-leaseholders to vacate their homes was 1 day, compared to 10 days for leaseholders.

It is no surprise that Massachusetts, which has among the highest cost of living and home prices in the country, would see a more significant increase in homelessness, However, there are other contributing national and state-specific factors contributing to the increase.

In 2024, there were 22,845 persons in families experiencing homelessness – a 74% increase from 2023. As noted in HUD’s findings, Massachusetts is one of many states that has seen a historic increase in immigration—specifically Haitian family households that are legal U.S. residents under temporary protective status. Massachusetts is the only state in the country with a statewide right to shelter law for families and pregnant persons, meaning that the state guarantees and must provide a place to stay for these groups if they are in need. While some stakeholders attribute the rise in homelessness in Massachusetts to an influx of immigrant or out-of-state families, there has also been a rise in longtime Massachusetts families experiencing homelessness because of rising housing costs and the end of the eviction moratorium in July 2021 that prevented households from falling into homelessness during the Covid-19 pandemic.

Attention to current challenges caused by the significant growth in family homelessness has also attracted less attention to the quieter crisis of the rising rate of individual adults experiencing homelessness. In 2024 there were 6,950 unaccompanied adults experiencing homelessness, the highest on record and a 12% increase from 2023. As noted earlier, single adults are not covered by the Right to Shelter law and often rely on community-based shelter that is primarily provided through community-based organizations through funding from HLC as well as federal, local, and philanthropic support. Unfortunately, shelter capacity is not sufficient for the need, operates on a first-come-first serve basis, and is often not utilized by many homeless individuals due to a variety of personal factors including but not limited to: safety concerns, separation from romantic partners given shelters are often single-sex, and challenges related to substance-use disorder and/or mental illness. The 2024 count showed a 19.9% increase in individuals experiencing unsheltered homelessness.

Similar to other housing disparity trends outlined in this plan, homelessness is a racial equity issue as persons of color disproportionately experience homelessness nationwide—particularly African Americans who account for 40% of total persons experiencing homelessness but only 13% of the general population. This trend is even more pronounced in Massachusetts where 54% of the state’s homeless population is African American but only account for 6.5% of the general population. Though less pronounced, Hispanic or Latino individuals account for roughly 30% of the total homelessness population yet represent just 12.6% of the state population.

People experiencing homelessness are not a monolithic population and require differing levels of government assistance to meet their housing needs. A family who just got evicted requires different supports than a single adult with co-occurring mental health and substance-use disorder that has experienced long-term unsheltered homelessness. In an ideal state, efforts to address homelessness are structured to meet the specific needs of varying populations in order to maximize limited government resources in a manner informed through an overarching goal to make homelessness rare, brief, and non-recurring. This includes upstream, cost-effective preventive efforts to prevent homelessness in the first place, such as RAFT outlined elsewhere in the plan. However, despite RAFT being among the most utilized government assistance programs, many people still fall into homelessness. Government assistance and programs are designed to ensure the level of assistance is aligned with the acuity of the person experiencing homelessness. This may include rapid rehousing funding to help individuals pay upfront costs or initial rental assistance that they can support through their income, front-door interventions to help persons identify housing support through family, and in the case of persons experiencing long-term homelessness, providing permanent supportive housing.

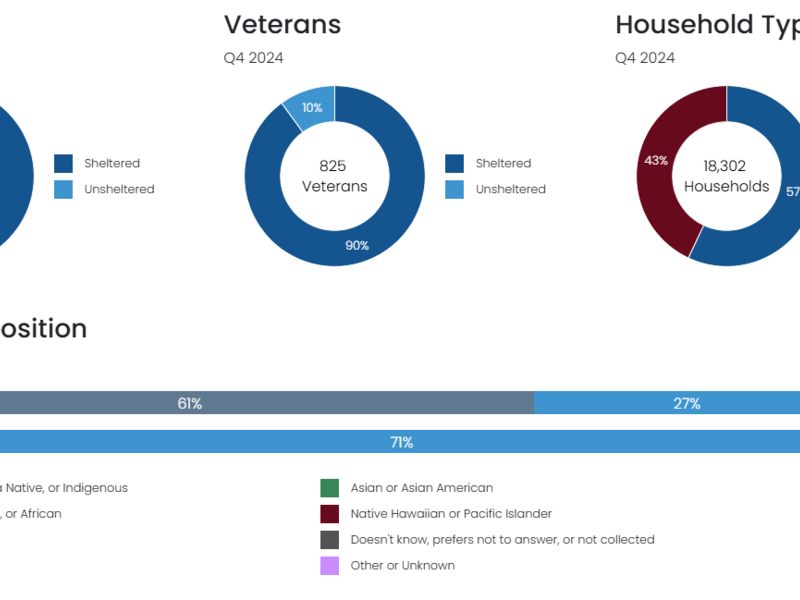

The federal and state response to homelessness has shifted over the last two decades towards prioritizing funding for permanent supportive housing (PSH) given strong empirical evidencedemonstrating the effectiveness of this solution. PSH is designed to address both the housing and accompanying health-related needs for individuals and families experiencing long-term or chronic homelessness—defined by HUD as a person with a disabling condition that has been homeless for 12 consecutive months or experienced homelessness on 4 separate occasions over the course of 3-years that equals at least 12 months. Individuals experiencing chronic homelessness are more likely to experience unsheltered homelessness, utilize costly emergency healthcare services (e.g., emergency departments, inpatient treatment), and intersect with the criminal justice system. The cyclical nature of the intersection with these systems followed by a return to homelessness results in increased taxpayer spending, poorer health outcomes including higher mortality rates, and ultimately a government response that does not address individuals’ underlying housing needs and fosters distrust towards future intervention efforts. As noted earlier, supportive housing requires a high level of government assistance, which hinders the ability to provide it at scale, and thus, must be prioritized for those most in need. As of November 2024, an estimated 16% of households in Massachusetts, 2,240 out of 13,770, are experiencing chronic homelessness. Similar to national trends, approximately 89% of chronically homeless households are single adults with only 250 family households identified as chronic homelessness. It is important to note that Massachusetts’ efforts to utilize real-time data to observe emerging trends and better inform interventions addressing homeless is impacted by varying structural challenges.

As noted earlier, federal funding and required measurements on persons experiencing homelessness, with some exceptions for family households, are overseen at a local level through Continuums of Care (CoCs) – homelessness response planning groups that are accountable to the federal government (HUD). Massachusetts has 11 CoCs plus the Emergency Assistance system overseen by HLC—which is relatively high when looking at Connecticut, which is approximately half Massachusetts’ size but has just two CoCs. Each of the eleven CoCs in Massachusetts has distinct plans and strategies for use of federal permanent supportive housing funds, different mechanisms for determining eligibility and prioritization for programs supported by those funds, distinct applications for those funds (each of which takes hundreds of hours to prepare), annual homelessness assessment reports, housing inventory charts, and point in time counts submitted to HUD. All of this results in needless administrative redundancy, confusion for people trying to navigate the system, and disparity in CoC funding across the Commonwealth. The Rehousing Data Collective (RDC) was established by HLC to provide a collective source of data on homelessness; however, it does not address many of the noted challenges regarding this structure as well as existing data issues across multiple CoCs. CoCs have not uniformly prioritized data quality and uploads to the RDC, significantly limiting the ability to rely on this data warehouse for policy planning. As the CoCs have no contractual relationship with any state agency, it is difficult to align with and enforce shared priorities.

In the face of record levels of homelessness, it is important to note that Massachusetts has long been a national leader in addressing homelessness even when responding to significant demand. Massachusetts has one of the lowest rates of unsheltered homelessness in part because Massachusetts is the only state in the country that guarantees a right-to-shelter for eligible families and pregnant persons. Boston, which has the highest homeless population in the State, has the 8th lowest rate of unsheltered homelessness in the country at 6%—substantially lower than the national average of 40%. Massachusetts is also the first state to receive approval from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) to allow for Medicaid-reimbursement for tenancy support services.