- Scientific name: Megaptera novaeangliae

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

The humpback whale is a medium-sized baleen whale than can live up to 90 years (NOAA 2025). Instead of teeth, baleen whales have a single row of baleen plates in their upper jaw which is used much like a strainer. Humpbacks have 270 to 440 baleen plates on each side of their upper jaw. After taking in large mouthfuls of water and fish, these baleen plates allow humpbacks to push water out while keeping fish trapped inside. The baleen plates are 0.6-0.7 m (24-28 in) in length.

Humpback whales reach a length of 18 m (60 ft) and weight of 36 mt (40 tons, NOAA 2025). Like most baleen whales, females tend to be larger than males. In the North Atlantic, most humpbacks have white flippers (possibly to scare fish) which are very long, almost a third of their body length. At up to 15 feet, these are the largest limbs in the animal kingdom. Tubercules each containing hair follicles on their head, snout, and flippers are one of the characteristics that distinguish humpback whales. Tubercles are golfball-sized bumps that help humpbacks sense their surroundings and provide maneuverability to flippers while hunting prey (Fish et al. 2011). The humpback's body is mainly dark grey with varying amounts of white underneath. Often, humpback whales raise their tails high in air before going down on a deep dive. Their dorsal fins are relatively small and vary in size and shape. The shape of this fin, along with any scars, is also used to help identify individual whales. However, sighting of the blow or spout, from a whale exhaling at the surface, is usually the first indication that a whale is in the area. For humpbacks, this blow or spout is about 3 m high (10 ft) and rather bushy in shape.

Life cycle and behavior

Humpback whales are the stars of the whale watching industry off the Massachusetts coast. Behaviors include spyhopping (poking their heads out of the water so their eyes are above the surface), logging (resting or sleeping at or just below the surface of water), flipper slapping (slapping long pectoral fins against the surface of the water), breaching (jumping out of the water), and feeding. Humpbacks feed on schooling fish and other small marine animals, which include sand lance, herring, and krill. They use various methods when catching their prey, including bubble feeding, lunge feeding, and stunning their prey by hitting them with their flippers and flukes.

Sexual maturity in humpbacks is reached between 6 and 10 years of age and physical maturity is reached between 12 and 15 years. In the Northern Hemisphere, births occur between January and March. A humpback gives birth to a single calf after a gestation period of 11 to 12 months. Contributing factors to the mortality of calves include predation and red-tide toxins. The greatest cause of natural mortality among calves are attacks by killer whales (Orcinus orca) and sharks. Tooth scars can be seen on the flippers and flukes of humpbacks from encounters with killer whales.

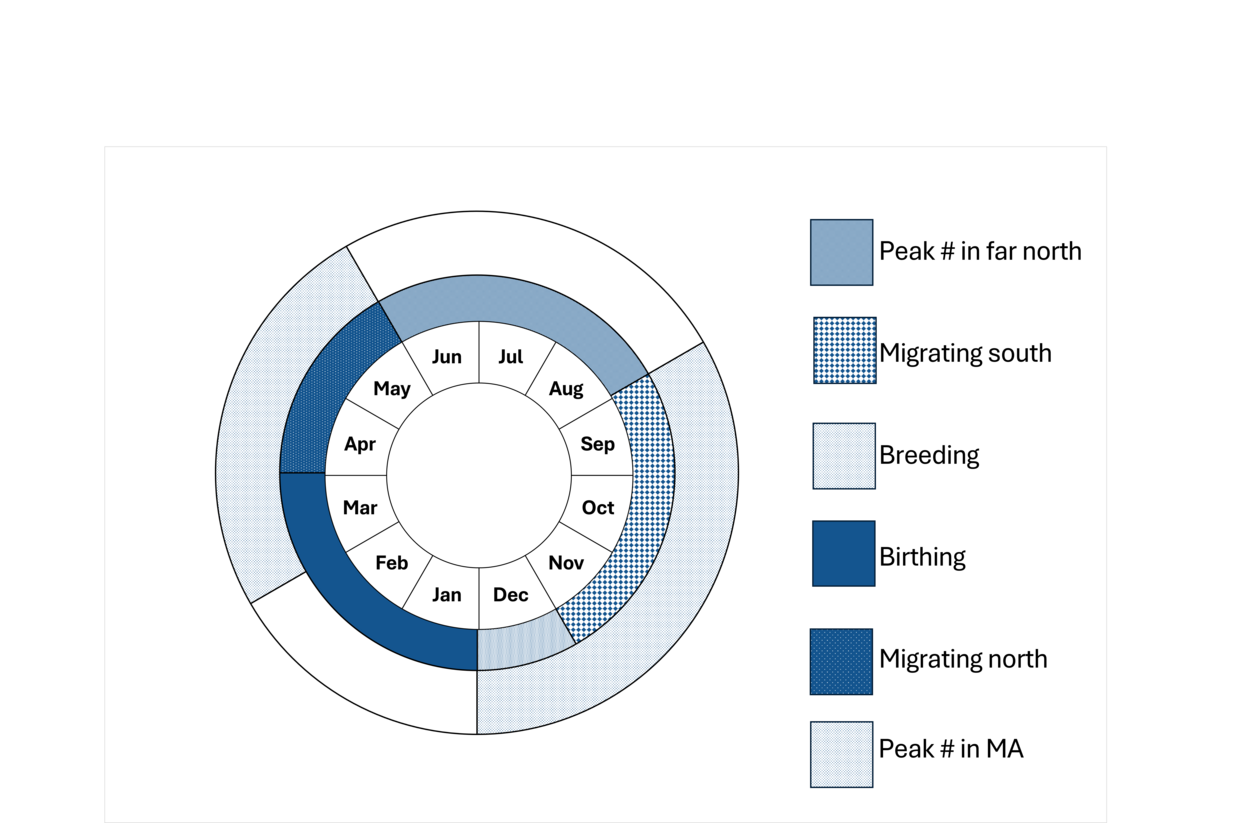

Adult male and female humpbacks in the North Atlantic migrate to low latitudes in the Caribbean to breed from December-April. Many adult males, as well as some nonbreeding females and juveniles/subadults, over-winter on northern feeding grounds, including from the mid-Atlantic to as far north as Franz Josef Land (Russia). Calves are born in warm waters of the breeding and calving grounds, then start migrating north alongside their mothers in March to their northern feeding grounds. Most calves spend one year alongside their mother, nursing on fatty milk, learning the migration route, and eventually learning to feed on their own. Humpback whales in the North Atlantic show high site fidelity to their northern feeding grounds. Off Massachusetts, humpbacks are often found feeding between March and November. One whale, Salt, has been sighted on Stellwagen Bank off Massachusetts since the 1970s.

Shifts in migration

Humpback whales have been shifting migration timing in recent years. Humpback whales shifted their peak habitat use in Cape Cod Bay 19.1 days earlier from 1998 to 2018, an average of 0.96 days/year (Staudinger et al. 2024 and references therein). Humpbacks arrived in the Gulf of St. Lawrence 28 days earlier in 2010 than they did in 1984 and left around 27 days earlier during the same time frame, remaining in the Gulf for about the same amount of time each year. A recent study (Roberts et al. 2025) suggests that humpback whale distribution and densities are also changing at local scales within the Gulf of Maine due to increases in prey abundance, increasing temperatures, and decreasing salinity. Further shifts are likely as the oceans continue to warm. Climate models exploring shifts in sea surface temperature due to climate change project that by 2100, anywhere between 35-67% of all global humpback whale breeding grounds will be warmer than their current range of breeding temperatures (von Hammerstein et al. 2022 in Staudinger et al. 2024).

Population status

Humpback whales around the world are classified into 14 Distinct Population Segments (DPS) based on their breeding grounds (Jones et al. 2025 and references therein). Humpback whales foraging in the Gulf of Maine (and Massachusetts) belong to the West Indies DPS which was designated as Not at Risk under the federal Endangered Species Act in 2016. However, it remains listed under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act. There are currently about 13,000 humpbacks estimated in the North Atlantic Ocean, and as of 2020, about 1,400 were using the Gulf of Maine. In 2017, NOAA declared an “Unusual Mortality Event” for humpback whales on the U.S. Atlantic Coast due to ongoing anthropogenic threats (e.g., ship strikes and fishing gear entanglement; NOAA 2017). This event is still ongoing. As of 2024, 232 dead humpback whales have been documented. Of 90 necropsied, about 40% were confirmed to have died from ship strikes or fishing gear entanglements.

Distribution and abundance

The humpback whale is found worldwide but is less common in arctic waters. Most migrate annually between feeding and breeding grounds. Winters are spent in warmer waters where there is little or no food, therefore, humpbacks mostly fast during periods on the breeding and calving grounds. Summers are spent foraging in northern areas, including the Gulf of Maine.

Approximate representation of the humpback whale's range (Image: NOAA/Fisheries)

Habitat

Humpback whales feed in waters off Massachusetts from spring through fall. Common areas to find whales locally include waters off Cape Ann and Cape Cod in the months of April through October. During the winter months, Gulf of Maine humpbacks migrate to the breeding and calving grounds in the West Indies, including to the Silver and Navidad banks north of the Dominican Republic, and off Puerto Rico.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has determined that although the species is increasing in abundance throughout much of its range, it still faces threats from vessel strikes, climate change, fishing gear entanglement, vessel-based harassment, and underwater noise (NOAA 2025). The text below is from their website.

Vessel strikes

Inadvertent vessel strikes can injure or kill humpback whales. Humpback whales are vulnerable to vessel strikes throughout their range, but the risk is much higher in coastal areas with heavier ship traffic.

Climate change

The impacts of climate change on whales are unknown, but it is considered one of the largest threats facing high latitude regions where many humpback whales forage. Most notably, the timing and distribution of sea ice coverage is changing dramatically with altered oceanographic conditions. Any resulting changes in prey distribution could lead to changes in foraging behavior, nutritional stress, and diminished reproduction for humpback whales. Additionally, changing water temperature and currents could impact the timing of environmental cues important for navigation and migration.

Entanglement in fishing gear

Humpback whales can become entangled by many different gear types, including vertical lines and netting associated with trap/pot and gillnet gear. Once entangled, whales may drag and swim with attached gear for long distances, ultimately resulting in fatigue, compromised feeding ability, or severe injury. These may lead to reduced reproductive success or even death. There is evidence to suggest that most humpback whales experience entanglement over the course of their lives but are often able to shed the gear on their own. However, the portion of whales that become entangled and do not survive is unknown.

Vessel-based harassment

Whale watching vessels, recreational boats, and other vessels may cause stress and behavioral changes in humpback whales. Because humpback whales are often found close to shore, they tend to be popular whale watching attractions. There are several areas within the United States where humpback whales are the central attraction for the whale watching industry, including the Gulf of Maine (particularly within the Stellwagen Bank National Marine Sanctuary), California, Alaska (particularly southeast Alaska), and the Hawaiian Islands.

Conservation

NOAA has identified the conservation actions most needed to promote humpback whale conservation (NOAA 2025). These are:

- Reducing the risk of entanglement in fishing gear,

- Developing methods to reduce vessel strikes,

- Responding to dead, injured, or entangled humpback whales,

- Educating the whale watching/tourism industry and vessel operators on responsible viewing of humpback whales, and

- Partnering to implement the Whale SENSE program, a whale watching stewardship, education, and recognition program to increase wildlife viewing standards.

Live, dead, or entangled right whales should be reported quickly to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s hotline at 866-755-6622.

References

Fish FE, Weber PW, Murray MM, and Howle LE. 2011. The tubercles on humpback whales’ flippers: application of bio-inspired technology. Integrative and Comparative Biology 51(1):203-213.

Jones LS, Allen JM, Balcomb KC, Basran CJ, Berrow SD, Betancourt L, Bouveret L, Boye TK, Broms F, Chosson V,…and Todd SK. 2025. Ocean basin-wide movement patterns of North Atlantic humpback whales. Journal of Cetacean Research and Management: https://doi.org/10.47536/jcrm.v26i1.951.

Morell V. 2016. Most humpback whales no longer endangered, United States says. Science: doi: 10.1126/science.aah7274.

National Marine Fisheries Service. 1991. Final Recovery Plan for the humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae). National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, MD. 105 pp.

NOAA [National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration]. 2016. Endangered and Threatened Species; Identification of 14 Distinct Population Segments of the humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) and Revision of Species-wide Listing. Federal Register 81(174):62260-62320. https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/FR-2016-09-08/pdf/2016-21276.pdf

NOAA. 2017. Humpback whales are dying on the East Coast. NOAA wants to know why. | National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Accessed on 6/17/25.

NOAA. 2024. 2016-2024 humpback whale Unusual Mortality Event Along the East Coast. NOAA Fisheries web site. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/marine-life-distress/2016-2024-humpback-whale-unusual-mortality-event-along-atlantic-coast

NOAA. 2025. Humpback Whale | NOAA Fisheries Accessed on 6/6/25.

Roberts SM, Dowd S, Thorne L, Roberts JJ, Halpin PN, Khan C, … Nye, JA. 2025. Humpback whale densities are increasing in the Great South Channel: concurrent multi-trophic level shifts in abundance. Marine Ecology Progress Series754:105–119. Available at: https://doi.org/10.3354/meps14781

Staudinger MD, Karmalkar AV, Terwillinger K, Burgio K, Lubeck A, Higgins H, Ricer T, Morelli TL, and D’Amato A (and references therein). 2024. A regional synthesis of climate data to inform the 2025 State Wildlife Action Plans in the Northeast U.S. DOI Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center Cooperator Report. 406 p. https://doi.org/10.21429/t352-9q86.

Contact

| Date published: | July 7, 2025 |

|---|