- Scientific name: Somatochlora incurvata

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Male incurvate emerald

The incurvate emerald (Somatochlora incurvata) is a large, slender insect of the order Odonata, suborder Anisoptera (the dragonflies), family Corduliidae (the emeralds). Most striped emeralds (Somatochlora) are large and dark with at least some iridescent green coloration, brilliant green eyes in the mature adults (brown in young individuals), and moderate pubescence (hairiness), especially on the thorax. Incurvate emeralds have two indistinct yellowish ovals (which fade with age), the front one more elongate, on each side of the thorax. The thorax overall is of a bronzy brown color with metallic green highlights throughout and long pale hairs. The face is very dark overall, with a bright yellow “upper lip.” The large eyes, which meet at a seam on the top of the head, are brilliant green in mature adults. The long and slender abdomen, black with a dull metallic green luster, is most narrow at the base, with a yellow lateral spot on segment 2, a pale basal ring on segment 3, and dull yellowish lateral spots on segments 4-8. The wings of this species are transparent and, as in all dragonflies and damselflies, are supported by a dense system of dark veins.

Adult incurvate emeralds range from 49 to 59 mm (1.9 to 2.3 in) in length. Females are stockier than males and have a pale-yellow ovipositor parallel to the abdomen. Final instar nymphs can range from 16 to 22 mm (0.6 to 0.9 in) in length.

Incurvate emeralds are distinguished from other striped emeralds in Massachusetts by the thoracic and abdominal markings and by the shape of the terminal appendages (part of the reproductive structures). Definitive identification requires examination of the shape of the male terminal abdominal appendages or the female’s large triangle-shaped vulvar lamina or subgenital plate that lies parallel to the abdomen (Lam 2024). Therefore, identification usually requires species in-hand accompanied by a hand lens or macro camera lens. Forcipate emerald is most like incurvate emerald but has two oval contrasting yellow thoracic spots unlike incurvate with an anterior stripe and posterior spot.

The nymphs and exuviae can be distinguished by characteristics as per the keys in Needham et al. (2000), Soltesz (1996), and Tennessen (2019).

Life cycle and behavior

Although little has been published about the life cycle of the incurvate emerald in particular, information documented for other species is most likely applicable. The egg and nymph life stages of the incurvate emerald are fully aquatic. The cryptic nymphs are predators, feeding on a wide variety of aquatic insects, small fish, and tadpoles. Nymphs undergo several molts (instars) for at least 2 years until they are ready to emerge as winged adults. Nymphs emerge up onto emergent vegetation or other stable substrate. When the nymph reaches a secure substrate, the adult begins to push itself out of the exoskeleton. As soon as the abdomen and wings are fully expanded, the adult takes its first flight. This maiden flight usually carries the individuals up into surrounding forest or other areas away from water, where they spend several days maturing and feeding and are somewhat protected from predation and inclement weather. Incurvate emeralds can be found in fields and forest clearings foraging on small aerial insects, such as flies and mosquitoes, which are consumed while flying. When not feeding, incurvate emeralds rest hanging vertically or perch obliquely from tree or shrub branches. After about a week, adult coloration is acquired, and the dragonfly becomes sexually mature before returning to the breeding habitat to initiate mating.

Males patrol over bogs and wet depressions, usually no more than two feet above the surface of the water, in search of females. The joined pair quickly flies off into the surrounding upland habitat to mate. Following mating, oviposition (egg laying) occurs. Females of the genus Somatochlora oviposit alone and deposit their eggs directly into the water by tapping the tip of the abdomen on its surface. Incurvate emerald females oviposit in open pools and wet depressions in the bog.

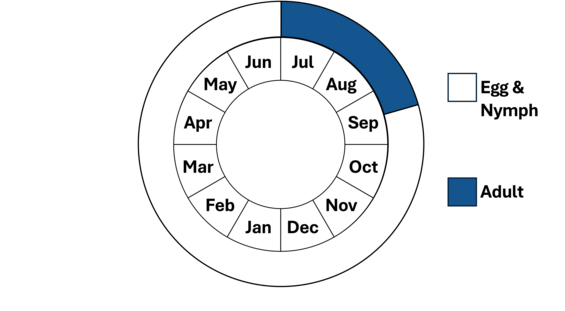

Adult incurvate emeralds are on the wing from early July to early September.

Distribution and abundance

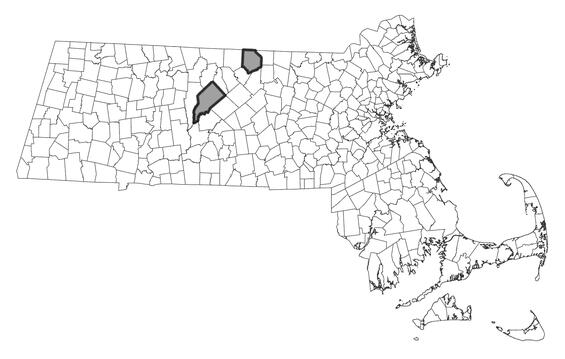

The incurvate emerald is a rare species that inhabits a narrow band along the southeastern Canadian border into the northeastern United States including Maine, New Hampshire, Vermont and Massachusetts as its southernly extent in New England. Incurvate emerald has been recorded at 3 sites in the north-central Massachusetts within the Millers and Swift River watersheds. The species has been observed in low to moderate abundance with variable breeding evidence.

The incurvate emerald is listed as endangered in Massachusetts and has been cited in just four sites. As with all species listed in Massachusetts, individuals of the species are protected from take (picking, collecting, killing, etc.) and sale under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

In Massachusetts, the incurvate emerald inhabits large acidic sphagnum bogs. These bogs have shallow open pools or depressions where breeding occurs. The adults also inhabit forested uplands and clearings.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Acidic sphagnum-dominated dominated bog habitat typical for incurvate emerald.

Threats

The greatest threat to this species is likely loss and degradation of wetlands from development and the impacts of pollution resulting from road run-off including salt and chemical pollutants. Additional threats include loss of upland forests needed for adult development and water-level manipulation from beavers and humans. Climate change poses a potential threat for the persistence of incurvate emerald in Massachusetts as its southern range limit is in Massachusetts.

Conservation

Surveys should target known sites and new wetlands to determine incurvate emerald occupancy. Although the species has been detected from only three sites, the species has the potential to occupy other potentially suitable bogs in northern Massachusetts. Surveys should target adults in feeding and breeding habitats, where the species is mostly likely to be detected. Multiple site visits (e.g., >3) are likely required to detect this species because of its rarity and its difficulty to capture by net or camera. Known sites should be monitored at least every 5 years to document changes in occupancy and habitat conditions.

Management

Land and wetland protection is critical for the conservation of incurvate emerald. Upland habitats adjoining the breeding sites should be maintained for roosting, hunting, and for newly emerged adults that are more susceptible to mortality from predation and inclement weather. Development of these areas should be discouraged, and the preservation of remaining undeveloped uplands should be a priority. Alternatives to commonly applied road salts should tested to minimize freshwater salinization. Management of beaver-induced water levels may be needed to minimize bog habitat degradation.

Research needs

Research effort is needed to estimate occupancy and detection rates for this species as species detection is likely low and inhabit other bogs. The effects of climate change on incurvate emerald and climate resistance of its aquatic-nymphal habitat, including water temperature and water quantity, warrant further investigation. Furthermore, confirmation of known and identification of new source and sink wetlands are needed to accurately assess the species risk to anthropogenic threats.

References

Dunkle, Sidney W. Dragonflies Through Binoculars. Oxford University Press, 2000.

Lam, E. Dragonflies of North America. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2024.

Mills, P.B. Somatochlora of Southern Ontario. Self-published, 2015.

Needham, J.G., M.J. Westfall, Jr., and M.L. May. Dragonflies of North America. Scientific Publishers, 2000.

Nikula, B., J.L. Ryan, and M.R. Burne. A Field Guide to the Dragonflies and Damselflies of Massachusetts. 2nd ed. Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, 2007.

Paulson, D. Dragonflies and Damselflies of the East. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Soltesz, K. Identification Keys to Northeastern Anisoptera Larvae. Center for Conservation and Biodiversity, University of Connecticut, 1996.

Tennessen, K. Dragonfly Nymphs of North America: An identification guide. Springer, 2019.

Walker, E.M., and P.S. Corbet. 1975. The Odonata of Canada and Alaska, Vol. III. University of Toronto Press.

Contact

| Date published: | March 5, 2025 |

|---|