Watershed Background

A watershed is the geographic catchment area for a body of water, such as a river, stream, lake, wetland, or estuary. All surface water (and most groundwater) within a given watershed flows downhill to the water body. As water bodies drain one to another, smaller watersheds are often nested within larger watersheds. All land area is part of a watershed, because all land drains eventually to a water body.

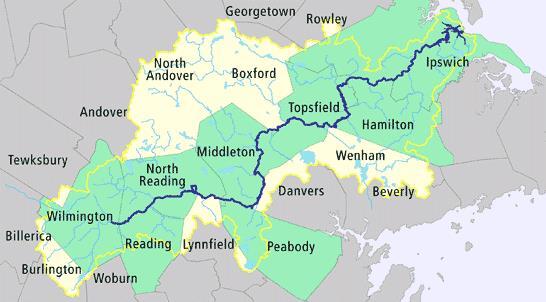

The Ipswich River winds 45 miles from Burlington, Massachusetts, to Plum Island Sound in the town of Ipswich. The Ipswich River watershed (all the land, streams, ponds, and wetlands that drain to the Ipswich River) is 155-square-miles and encompasses all or part of 21 communities. The watershed has been an economic and ecological asset within northeastern Massachusetts since pre-colonial times. The river supports productive fisheries and shellfish beds and for over a hundred years has powered shipbuilders, tanneries, and textile mills. The streams and aquifers in the watershed also provide drinking water to hundreds of thousands of people both within and outside of the watershed boundaries.

But the Ipswich River and its tributaries are in trouble. American Rivers, a national rivers protection organization, named the Ipswich River one of the most endangered rivers in the country. This designation reflects the severe reductions in flow the river has experienced, particularly since the mid-1990s. Since then, long sections of the river have dried up altogether, several times.

Where is the Water in the Ipswich Going?

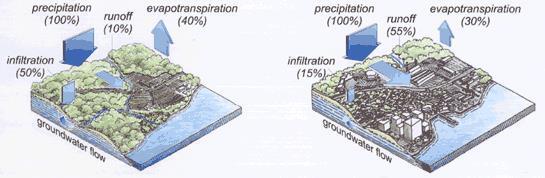

High water demand, the pumping of water out of the watershed, and changes in land use have all contributed to low-flow conditions in the Ipswich River watershed. The diagram above shows what happens when forest land is converted into to urban development. More rainfall runs directly off the hard urban surfaces like pavement and rooftops into nearby streams (runoff), and quickly out to the ocean. Less rainfall soaks into the ground (infiltration) to serve as a source of slow, sustained flow into the streams and river. This leads to more floods during rain storms and lower river flows between rain storms.

Key Watershed Facts

- The Ipswich watershed supplies drinking water to 330,000 residents and businesses in 15 communities. Nearly 80% of the water withdrawn is piped to areas outside of the watershed, either as drinking water or wastewater.

- Landscape irrigation is a major stress on the Ipswich River. Studies indicate that the amount of water needed to restore natural flows is about equal to the estimated amount used for lawn watering throughout the watershed.

- The amount of water pumped in summer is often twice the year-round average. This is mostly due to lawn watering.

- The watershed is developing rapidly. Since 1971, an average of almost 1,000 acres per year have been developed in the Ipswich watershed.

Source: Ipswich River Watershed Action Plan. October 2003. Prepared by Horsley & Witten, Inc., for the Massachusetts Executive Office of Environmental Affairs.

An Integrated Solution

The Massachusetts Department of Conservation and Recreation (DCR) received a $1.04 million grant from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Targeted Watersheds Grant program to demonstrate an integrated approach to addressing the problems facing the Ipswich River. This approach encompassed two strategies:

- Low-Impact Development (LID) – landscape and design techniques that capture stormwater and recharge it to the groundwater

- Water Conservation – education strategies and technologies that reduce demand on water supplies, and associated groundwater pumping, especially during summer months

Nine demonstration projects were implemented in all. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) used data collected from the demonstration projects in a watershed computer model that simulated the effect on river flows if these low-impact development and water conservation techniques were to be applied throughout the watershed.

Low-Impact Development (LID) Demonstrations

Four projects demonstrated low-impact development approaches and their potential to decrease stormwater runoff and nonpoint source pollution and to enhance groundwater recharge:

- LID subdivision

- Green roof

- Permeable paving and bioretention in a beach parking lot

- LID retrofits in a lake-side neighborhood

Water Conservation Demonstrations

Five projects demonstrated innovative water conservation approaches and their potential to reduce water demand:

- Rainwater harvesting

- Soil and turf amendments at municipal athletic fields

- Municipal water conservation program for households

- Weather-based irrigation controllers

- Monthly water billing

These demonstration projects were located in eight communities within the Ipswich River watershed, shown in green below.