- Scientific name: Somatochlora kennedyi

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Male Kennedy’s emerald

Kennedy’s emerald (Somatochlora kennedyi) is a large, slender insect belonging to the order Odonata, sub-order Anisoptera (the dragonflies), and family Corduliidae (the emeralds). Most striped emeralds (Somatochlora), which includes Kennedy’s emerald, are generally large, dark dragonflies with at least some iridescent green coloration, brilliant green eyes in the mature adults (brown in young individuals), and moderate pubescence (hairiness), especially on the thorax. The face of the Kennedy’s emerald is mostly brown. The large eyes, which meet at a seam on the top of the head, are brilliant green in mature adults, brown in less mature individuals. The thorax is metallic green and brown with a pale-yellow anterior lateral stripe and usually without a faded yellow posterior lateral spot but may be present in some individuals. The cylindrical abdomen is highly constricted at its base, widening to segment five and then narrowing slightly towards the distal end. The abdomen is black with a metallic green sheen. In the females, segments 1 and 2 have extensive dorsal spots. The wings of this species are transparent and are supported by a dense system of dark veins.

Adult Kennedy’s emeralds range from 51 to 55 mm (1.9 to 2.2 in) in length. Male and female Kennedy’s emeralds are similar in coloration, though the female is larger. Final instar nymphs can range from 18 to 21mm (0.7 to 0.8 in) in length.

Adult Kennedy’s emerald is like other species of striped emeralds in Massachusetts, though several characters can help distinguish it from all other species. Definitive identification requires examination of the shape of the male terminal abdominal appendages or the female’s yellow to orange, short scoop-shaped vulvar lamina or subgenital plate that lies almost parallel to the abdomen (Lam 2024). Therefore, identification usually requires species in-hand accompanied by a hand lens or macro camera lens. Similar species include incurvate (S. incurvata), forcipate (S. forcipate) and Williamson’s emeralds (S. williamsoni) when individuals are older and thoracic markings have faded. However, these species possess two lateral thoracic stripes or spots and lateral abdominal spots while Kennedy’s emerald has one thoracic mark and no lateral abdominal spots.

The nymphs and exuviae can be distinguished by characteristics as per the keys in Needham et al. (2000), Soltesz (1996), and Tennessen (2019).

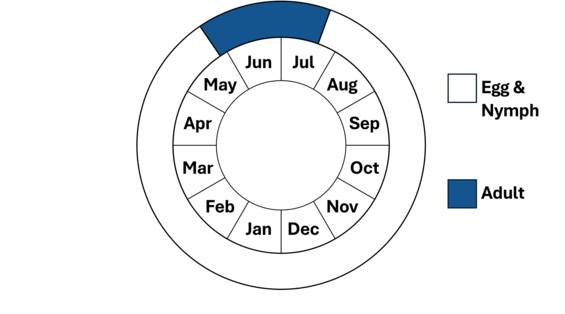

Life cycle and behavior

Note, nymphs are present year-round.

Although little has been published about the life cycle of the Kennedy’s emerald in particular, information documented for other species is most likely applicable. The egg and nymph life stages are fully aquatic. The cryptic nymphs are predators, feeding on a wide variety of aquatic insects, small fish, and tadpoles. Nymphs undergo several molts (instars) for at least 2 years until they are ready to emerge as winged adults. Nymphs emerge up onto emergent vegetation, tree roots, stream banks, or other stable substrate. When the nymph reaches a secure substrate, the adult begins to push itself out of the exoskeleton. As soon as the abdomen and wings are fully expanded, the adult takes its first flight. This maiden flight usually carries the individuals up into surrounding forest or other areas away from water, where they spend several days maturing and feeding and are somewhat protected from predation and inclement weather. Kennedy’s emerald can be found in fields and forest clearings foraging on small aerial insects, such as flies and mosquitoes, which are consumed while flying. The species is known to join feeding swarms at dawn and dusk. When not feeding, forcipate emeralds rest hanging vertically or perch obliquely from tree or shrub branches. After about a week, adult coloration is acquired, and the dragonfly becomes sexually mature before returning to the breeding habitat to initiate mating.

Breeding in Massachusetts probably occurs from mid-June through early July, as in other regions where this species occurs. At the breeding habitat, male dragonflies spend much of their time seeking out females and driving off competing males. Male patrol the more shaded portions of streams where they often hover in one location and will occasionally come to rest upon low bushes before quickly resuming their patrol for females. A joined pair quickly flies off into the surrounding upland habitat to mate.

Following mating, oviposition occurs. Females of the genus Somatochlora oviposit alone and deposit their eggs directly into the substrate by tapping the tip of the abdomen on its surface. Kennedy’s emeralds are known to prefer oviposition sites in the more shaded portions of their stream habitat. In these shaded areas, they can be seen ovipositing in the more densely vegetated or floating moss-covered areas.

Kennedy’s emerald is the earliest flying striped emerald in Massachusetts. It has been recorded as early as late May and generally flies only into early July when most other species are just beginning their flight season.

Population status

Kennedy’s emerald is listed as endangered in Massachusetts. As with all species listed in Massachusetts, individuals of the species are protected from take (picking, collecting, killing, etc.) and sale under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act.

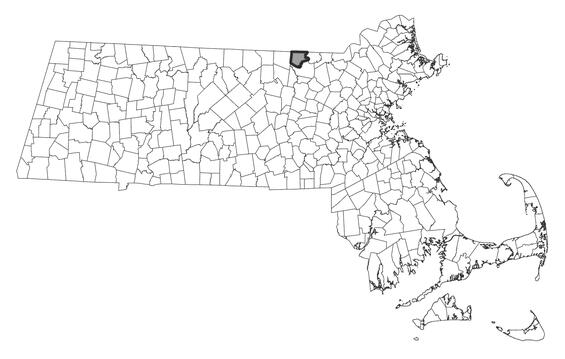

Distribution and abundance

Kennedy’s emerald is distributed from the Maritime Provinces to Manitoba and the Northwest Territories, south to Massachusetts, northern New York, Ohio, Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. Massachusetts lies at the species most southern extent. Kennedy’s emerald has been recorded at 3 sites in north and southeastern parts of the state with the species not recorded in almost 20 years. Breeding behavior and locations have never been observed in Massachusetts.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

In Massachusetts, the Kennedy’s emerald has been found inhabiting small streams and red maple swamps. Elsewhere in its range, Kennedy’s emerald is associated with open bogs and fens dominated by moss and sedges with or without flowing water. The adults also inhabit forested uplands and clearings where the species has been most observed in Massachusetts.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

The greatest threat to this species is likely loss and degradation of streams and associated wetlands from development and the impacts of pollution resulting from road run-off including salt, chemical pollutants, and excessive nutrients. Additional threats include loss of upland forests needed for adult development and water-level or flow manipulation from beavers and humans. Climate change poses a potential threat for the persistence of Kennedy’s emerald in Massachusetts as its southern range limit is in Massachusetts.

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

Surveys should target known sites and new streams and bogs to determine Kennedy’s emerald occupancy. Although the species has been detected from only three sites, the species has the potential to occupy other wetland systems in Massachusetts. Surveys should target adults in feeding and breeding habitats, including feeding swarms at dawn and dusk, where the species is mostly likely to be detected. Multiple site visits (e.g., >3) are likely required to detect this species because of its rarity and its difficulty to capture by net or camera. Known sites should be monitored at least every 5 years to document changes in occupancy and habitat conditions. Identification of breeding wetlands is a priority.

Management

Land and wetland protection is critical for the conservation of forcipate emerald. Upland habitats adjoining the breeding sites should be maintained for roosting, hunting, and for newly emerged adults that are more susceptible to mortality from predation and inclement weather. Development of these areas should be discouraged, and the preservation of remaining undeveloped uplands should be a priority. Alternatives to commonly applied road salts should tested to minimize freshwater salinization. Management of beaver-induced water levels may be needed to minimize stream and associated wetland habitat degradation.

Research needs

Research effort is needed to estimate occupancy and detection rates for this species as species detection is likely low and they may inhabit other wetland systems. The effects of climate change on forcipate emerald and climate resistance of its aquatic-nymphal habitat, including water temperature and water quantity, warrant further investigation. Furthermore, confirmation of known and identification of new source and sink wetlands are needed to accurately assess the species risk to anthropogenic threats.

References

Dunkle, Sidney W. Dragonflies Through Binoculars. Oxford University Press, 2000.

Lam, E. Dragonflies of North America. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2024.

Mills, P.B. Somatochlora of Southern Ontario. Self-published, 2015.

Needham, J.G., M.J. Westfall, Jr., and M.L. May. Dragonflies of North America. Scientific Publishers, 2000.

Nikula, B., J.L. Ryan, and M.R. Burne. A Field Guide to the Dragonflies and Damselflies of Massachusetts. 2nd ed. Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, 2007.

Paulson, D. Dragonflies and Damselflies of the East. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Soltesz, K. Identification Keys to Northeastern Anisoptera Larvae. Center for Conservation and Biodiversity, University of Connecticut, 1996.

Tennessen, K. Dragonfly Nymphs of North America: An identification guide. Springer, 2019.

Walker, E.M. 1958. The Odonata of Canada and Alaska, Vol. II. University of Toronto Press.

Contact

| Date published: | March 6, 2025 |

|---|