Salt marshes are one of the most ecologically important coastal wetlands, providing rich habitat to a great diversity of wildlife, serving as nursery grounds for fish and shellfish, and helping to fuel food webs. In addition, salt marshes provide protection from storm damage by dispersing wave and tide energy and help purify water by filtering potential pollutants. For property owners adjacent to marshes, one of the most effective ways to help protect these resources is by planting a meadow buffer of native plants, particularly as a replacement for lawn.

But planting near salt marshes has its challenges—plants must tolerate wind, salt spray, temperature fluctuations, dry to wet conditions, storm surge, and even freshwater influx from stormwater runoff. Plants also need to be hardy enough to compete with invasive species. Rather than lawn—which struggles in these conditions and requires more maintenance—consider planting a meadow buffer of hardy, salt-tolerant, native plants that can withstand these fluctuations while offering many benefits, including stabilizing soils and reducing potential property damage, buffering stormwater runoff, improving wildlife habitat, beautifying the landscape, and offering a lower maintenance alternative.

NOTE: Salt marshes are a highly protected resource area under the Wetlands Protection Act and should not be altered in any way. Though native plantings in the upland buffer are beneficial, contact your local Conservation Commission to determine if a permit is necessary. Please see Coastal Landscaping - Do You Need a Permit? for more information. Also be sure to check with the Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program [NHESP] or their most recent Priority Habitat and Estimated Habitat Maps, which are available online to determine if the site is in or near mapped endangered or threatened species habitat.

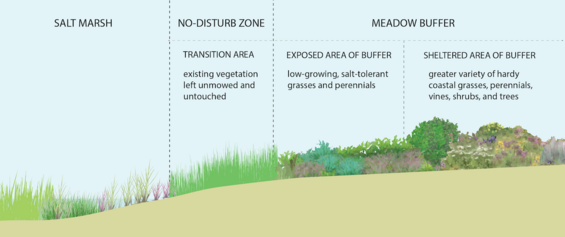

NOTE: Always maintain a no-disturb zone of about 3-4 feet between a meadow buffer and the salt marsh edge, leaving the existing vegetation (such as grass) unmowed. This transition area allows access to the meadow plantings (without having to step in the marsh) and helps prevent any exposed soils in newly planted meadow areas from being washed into the marsh. The no-disturb zone can also provide a transition area for sun-loving salt marsh grasses to grow and thrive without shade or competition. Just upland of the no-disturb zone, plant native grasses and perennials—and only plant shrubs in the more sheltered areas of the buffer farther landward and upland. See the Profile of a Meadow Buffer for an illustration and details on recommended plant types for these different zones.

For an example plan and plant list, see the Sample Landscape Plan for Meadow Buffer to Salt Marsh and for photos and additional information on plant species, see Coastal Landscaping in Massachusetts - Plant Highlights and Images.

Planting to Help Buffer Flood Waters and Filter Stormwater Runoff

A thickly planted meadow buffer is extremely useful for stabilizing soils and reducing shoreline erosion and property damage caused by storm surge. Low-growing native plants, such as big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii), little bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium), prairie dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepis), seaside goldenrod (Solidago sempervirens), and switchgrass (Panicum virgatum), are good choices for stabilizing soils and preventing erosion since they have deep and dense root structures and provide a thick cover. Farther landward, smaller-growing native shrubs such as bayberry (Morella caroliniensis), common juniper (Juniperus communis), red twig dogwood (Swida sericea), and Virginia rose (Rosa virginiana), along with larger shrubs such as beach plum (Prunus maritima) and winged sumac (Rhus copallinum), are also good options since they are hardy and tolerant of salt spray and drought and have extensive root systems that help bind soils.

Replacing lawn with a meadow buffer also provides significant stormwater management benefits. Native plants absorb and filter stormwater much more effectively than lawn, helping to remove nutrients, sediments, chemicals, and other pollutants before reaching the salt marsh and waterbodies beyond. And since native plantings do not require fertilizers and pesticides to thrive, any remaining runoff is free from further contamination. Hardy groundcovers and perennials that can quickly colonize an area and spread are particularly good choices. Wild strawberry (Fragaria virginiana) and barren strawberry (Geum fragarioides) are effective groundcovers that will sprawl and spread easily by rhizomes and runners, helping to cover exposed soils and slow and absorb water runoff. Native flowering perennials, such as blue vervain (Verbena hastata), golden Alexander (Zizia aurea), hyssop-leaved boneset (Eupatorium hyssopifolium), narrow-leaf mountain mint (Pycanthemum tenuifolium), and New York ironweed (Vernonia noveboracensis), are hardy, fast growing, and provide dense cover for filtering stormwater runoff while also offering beautiful pops of color and wildlife benefits (which are discussed in the next section).

Tip: Avoid using mulch, which can be carried away to the salt marsh from stormwater runoff. Instead, consider spacing plants close together to cover bare ground, which reduces the potential for weed growth, retains soil moisture, and limits erosion. A coir fiber blanket can also be used to hold soils in place while plants become established (for more information, see StormSmart Properties Fact Sheet 5: Bioengineering - Natural Fiber Blankets on Coastal Banks).

Planting to Enhance Wildlife Habitat and Aesthetics

Meadow plantings of sprawling native groundcovers, attractive bunch-forming grasses, thickly planted colorful wildflower perennials, and flowering/fruiting shrubs can also be planted to enhance wildlife habitat and landscape beauty. Meadows effectively cover bare ground (while not inhibiting views), provide important food resources, and create nesting areas, shelter, and corridors for wildlife. In addition to many of the species listed above, flowering perennials such as butterfly milkweed (Asclepias tuberosa), swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata), coastal plain Joe-Pye weed (Eutrochium dubium), Eastern showy aster (Eurybia spectabilis), New York aster (Symphyotrichum novi-belgii), narrow-leaf evening primrose (Oenothera fruticos), swamp mallow (Hibiscus moscheutos), and white goldenrod (Solidago bicolor) are host plants for hundreds of species of caterpillars, important sources of nectar and pollen for specialized bees and other insects, and valuable seed sources for songbirds. Shrubs planted farther landward can provide shelter, food, and places for birds to perch—and when planted as a stand-alone specimen, a shrub can provide a visually appealing focal point. In addition to the shrubs listed above, fruiting shrubs and vines such as arrowwood viburnum (Viburnum dentatum), fox grape (Vitis labrusca), gray dogwood (Swida racemosa), and winterberry (Ilex verticillata) provide food sources for wildlife, including migrating birds.

Tip: Leave dormant perennials standing through the winter so the plant material will continue to filter stormwater and act as a buffer to the salt marsh. The spent perennials and other standing vegetation also provide winter shelter and hiding spaces for insects, birds, and small mammals.

Tip: Within these buffers, leaf litter can be left on the ground to provide critical overwintering habitat for bees, moths, butterflies, and other beneficial insects (which the birds rely on as a source of food for their nestlings). The leaf litter can either be left in place to decompose naturally or carefully removed the following spring when temperatures have warmed enough for the insects to have departed their winter habitat.

Planting to Reduce Maintenance Needs

Planting native species in a meadow buffer to a salt marsh is a more resilient and lower maintenance option than lawn. Native plants have evolved in the local climate and are well adapted to the region's growing conditions, giving them a better chance of survival and establishment. Replacing lawn also eliminates time spent regularly mowing, watering, and applying fertilizers and pesticides. While it can take significant time and effort to remove lawn and ensure new plants become established, after a few years of growth and succession, meadows will eventually self-seed, help regenerate the soils with their organic matter, and require less weeding maintenance than lawns or typical landscape gardens.

Tip: Since meadows are ecosystems in transition, occasional mowing or cutting will be needed to maintain grasses and perennials (and the few selected shrubs and trees) and avoid a succession to a shrub/tree community that would shade and outcompete meadow plants. The meadow can either be mowed/cut or undesired species can be selectively removed. Mow or cut the area no more than once a year with a string trimmer, lawn mower, or brush hog set at a high level, and only in alternating sections per year—so that some areas are left untouched to best support plant flowering and seeding and to provide year-round habitat for pollinators and other wildlife. Never mow any part of the meadow right to the edge of the salt marsh—leave the vegetated no-disturb area along the marsh unmowed (and only hand pull or selectively cut undesired or invasive species).

Tip: To give plants their best start, watering will likely be necessary during the first year or two in the hotter, drier summer months. However, watering should be minimized to ensure that excess fresh water does not run off into salt marsh or tidal creeks. To reduce runoff, use temporary drip tubing/soaker hoses placed around new plants while the plants become established, and water only when rainfall levels are low. For more on watering guidance, see Tips for Planting, Installation, and Maintenance.

NOTE: Please do not place fill, edging materials, large rocks, or other materials in the meadow buffer—plantings should be installed on the existing grade (even when sloping toward the salt marsh). Loose fill has the potential to run off and smother salt marsh vegetation, and raised berms and other landscaping materials can deflect or redirect storm surge waters and cause erosion. Berms may also be a potential barrier for the expansion of salt marsh grasses as sea levels rise.

Profile of a Meadow Buffer to Salt Marsh

This profile illustration depicts the recommended transition of plant types from the edge of the salt marsh to the upland buffer. Closest to the salt marsh, existing vegetation should be left untouched in an area 3-4 feet wide as a no-disturb zone. This transition area also allows access to meadow plantings (without having to step in the marsh), and the existing vegetation will capture sediments that could be washed into the marsh before newly installed plants grow and fully cover exposed soils. In addition, this area provides space to allow for the potential expansion of salt marsh grasses as sea levels rise. Salt marsh grasses thrive with inundation, making them better able to disperse wave and tide energy than upland plants that will eventually die out as tides reach higher. Finally, leaving this area undisturbed will provide better protection from storm damage, while saving time and money needed to maintain and replace unsuccessful upland plants.

The area just beyond the no-disturb zone (exposed area of buffer) is where plants must be able to tolerate exposure to wind, salt spray, and occasional splashover and storm surge from extreme storm events. Grasses and perennials are encouraged here since their low growth prevents shading of nearby sun-loving salt marsh species in the summer, and their die back at the end of the growing season reduces the potential for damage during winter storms.

The most landward portion of the meadow buffer (sheltered area of buffer) is more protected from wind, salt spray, splashover, and potential storm surge. Here, the salt marsh buffer can host a greater variety of plant species, including particular shrubs and trees, which when set back will not threaten salt marsh species with shading impacts or suffer damage from wind, salt spray, or winter storms.

Selecting Plants

Plants growing near a salt marsh must be resilient enough to withstand variable conditions—potential storm surge, fluctuating soil moisture levels, and exposure to salt spray and wind. The following list includes appropriate plants. Photos and additional information are provided on the Plant Highlights and Images page. Also see the Sample Landscape Plan for Meadow Buffer to Salt Marsh for an example of a buffer design and plant list.

Salt Marsh Buffer Plant List

Plant List for Exposed Areas of the Salt Marsh Buffer

Plants for exposed areas of the salt marsh buffer (closer to the salt marsh) must be able to tolerate wind, salt spray, and occasional splashover and storm surge from extreme storms. These plants must also be low growing so that they do not cause potential shading of nearby salt marsh species. The plants listed below are appropriate for these conditions.

Grasses and Perennials

- Big Bluestem (Andropogon gerardii) (native)

- Coastal Plain Joe-Pye Weed (Eutrochium dubium) (native)

- Eastern Showy Aster (Eurybia spectabilis) (native)

- Hyssop-leaved Boneset (Eupatorium hyssopifolium) (native)

- Little Bluestem (Schizachyrium scoparium) (native)

- Mountain Mints, Hoary (Pycanthemum incanum) and Narrow-Leaf (P. tenuifolium) (native)

- Narrow-Leaf Evening Primrose, Sundrops (Oenothera fruticosa) (native)

- New York Aster (Symphyotrichum novi-belgii) (native)

- Prairie Dropseed (Sporobolus heterolepis) (native)

- Red Fescue (Festuca rubra ssp. pruinosa) (native; all other subspecies considered not native)

- Seaside Goldenrod (Solidago sempervirens) (native)

- Swamp Mallow (Hibiscus moscheutos) (native)

- Switchgrass (Panicum virgatum) (native)

Shrubs, Groundcovers, and Vines

- Bearberry (Arctostaphylos uva-ursi) (native)

- Marsh Elder (Iva frutescens) (native)

Plant List for More Sheltered Areas of the Salt Marsh Buffer

In the more landward areas of the meadow buffer—where plants are more sheltered from wind, salt spray, splashover, and potential storm surge—a greater variety of plants can grow. The plants listed below, as well as those listed above for exposed areas, are appropriate for these conditions.

Grasses and Perennials

- Blue Vervain (Verbena hastata) (native)

- Common Boneset (Eupatoriumperfoliatum) (native)

- Golden Alexander (Zizia aurea) (native)

- Pennsylvania Sedge (Carex pensylvanica) (native)

- Pink Tickseed (Coreopsis rosea) (native)

- Poverty Dropseed (Sporobolus vaginiflorus) (native)

- Purple Lovegrass (Eragrostis spectabalis) (native)

- Red Columbine (Aquilegia canadensis) (native)

- Sweet Goldenrod (Solidago odora) (native)

- Wavy Hairgrass (Deschampsia flexuosa) (native)

- White Goldenrod, Silverrod (Solidago bicolor) (native)

- Woodland Sunflower (Helianthus divaricatus) (native)

- Yellow Plume Grass (Sorghastrum nutans) (native)

Shrubs, Groundcovers, and Vines

- Arrowwood Viburnum (Viburnum dentatum) (native)

- Barren Strawberry (Geum fragarioides) (native to Massachusetts; introduced in some coastal areas)

- Bayberry (Morellacaroliniensis) (native)

- Beach Plum (Prunus maritima) (native)

- Bigleaf Hydrangea (Hydrangea macrophylla) (not native; native to Japan)

- Black Chokeberry (Aronia melanocarpa) (native)

- Common Juniper (Juniperus communis) (native)

- Eastern Ninebark (Physocarpus opulifolius) (not native; native to New York south to Florida and the Midwest)

- Elderberry (Sambucus canadensis) (native)

- Fox Grape (Vitis labrusca) (native)

- Gray Dogwood (Swida racemosa) (native)

- Highbush Blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) (native)

- Inkberry (Ilex glabra) (native)

- Lowbush Blueberry (Vaccinium angustifolium) (native)

- Nannyberry (Viburnum lentago) (native)

- New Jersey Tea (Ceanothus americanus) (native)

- Red Chokeberry (Aronia arbutifolia) (native)

- Red Twig Dogwood (Swida sericea) (native)

- Shrubby Cinquefoil (Potentilla fruticosa) (native)

- Spicebush (Lindera benzoin) (native)

- Sweet Fern (Comptonia peregrina) (native)

- Sweet Pepperbush (Clethra alnifolia) (native)

- Virginia Creeper (Parthenocissus quinquefolia) (native)

- Virginia Rose (Rosa virginiana) (native)

- Wild Raisin (Viburnum cassinoides) (native)

- Wild Strawberry (Fragaria virginiana) (native)

- Winged Sumac (Rhus copallinum) (native)

- Winterberry (Ilex verticillata) (native)

Trees

- American Holly (Ilex opaca) (native)

- American Sycamore (Platanus occidentalis) (native)

- Atlantic White Cedar (Chamaecyparis thyoides) (native)

- Black Cherry (Prunus serotina) (native)

- Black Tupelo (Nyssa sylvatica) (native)

- Downy Serviceberry/Shadbush (Amelanchier canadensis) (native)

- Eastern Red Cedar (Juniperus virginiana) (native)

- Gray Birch (Betula populifolia) (native)

- Pitch Pine (Pinus rigida) (native)

- Red Maple (Acer rubrum) (native)

- Red Oak (Quercus rubra) (native)

- Sassafras (Sassafras albidum) (native)

- Shagbark Hickory (Carya ovata) (native)

- Scarlet Oak (Quercus coccinea) (native)

- Tamarack (Larix laricina) (native)

- White Oak (Quercus alba) (native)

More Information

For more information about many of the plants that are listed above, visit the Native Plant Trust’s Go Botany and Garden Plant Finder pages, United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) Natural Resources Conservation Service's (NRCS) PLANTS Database, the University of Connecticut (UConn) Plant Database of Trees, Shrubs, and Vines, and the Lady Bird Johnson Wildflower Center Plant Database.

Caution with a Very Common Coastal Plant - Rosa Rugosa

Rugosa rose (Rosa rugosa) is considered to be non-native (native to eastern Asia) and potentially invasive in some regions or habitats of Massachusetts and may displace desirable vegetation if not properly managed. Though the shrub is extremely tolerant of sea spray and effective at directing pedestrian access away from dunes, it has the ability to form dense thickets that shade and outcompete other native bank, beach, and dune plants. Rugosa rose can also spread vigorously through both seed dispersal (carried by the rose hips) and underground rhizomes. Therefore, care should be taken when considering planting rugosa rose on coastal properties.