- Scientific name: Oceanodroma leucorhoa

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Leach’s storm-petrel (Oceanodroma leucorhoa)

Leach’s storm-petrels are relatively small, dusky-colored oceanic birds, 20 cm (8 in) in length with a 46 cm (20 in) wingspread, and long slender wings that are angled and swept back in flight. Characteristic of the family Hydrobatidae, Leach’s storm-petrels possess long, slim legs, webbed feet, and a pair of raised tubed nostrils on the upper mandible of their black bill. The overall plumage of this species is dark brownish black except for a prominent, tawny carpal bar that extends diagonally from the top leading edge of the wing to the rear edge of the wing near the body. Atlantic populations of Leach’s storm-petrels possess a white rump, usually bisected with dusky feathering that sometimes produces a “split-rumped” appearance in the field. The tail is prominently notched and extends beyond the trailing legs and feet in flight. Juvenile Leach’s storm-petrels are covered with a dark fuzzy gray down, although this plumage is rarely seen because juveniles remain in nesting burrows until ready to fledge. Though generally silent at sea, the nocturnal vocalizations of Leach’s storm-petrels near their nesting colonies consist of combinations of musical purring notes and a maniacal chuckling chatter given in flight. Leach’s storm-petrels are seldom seen from land, however when observed at sea they fly with deep, rowing wing beats frequently punctuated by erratic changes in direction. This bounding flight is often likened to that of a common nighthawk.

Life cycle and behavior

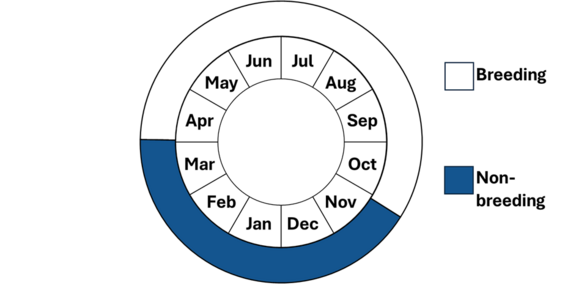

Figure 1. Phenology in Massachusetts. This is a simplification of the annual life cycle. Timing exhibited by individuals in a population varies, so adjacent life stages generally overlap each other at their starts and ends.

Like all Procellariiformes (tube-nose seabirds), Leach’s storm-petrels only return to land during the breeding season. They begin visiting breeding colonies in April and May. Leach’s storm-petrels are burrow and crevice nesting seabirds. Males dig burrows using their feet and bills, and will re-use nesting burrows, while also taking advantage of natural holes and crevices. Territory size in this species hardly exceeds that of the nesting burrow, but courtship behavior is elaborate, involving nocturnal flights over the colony and vocalizations from females while on the wing and males in the burrows. Nests located in these burrow chambers are spartan, normally consisting of only a few stalks of vegetation, feathers, or pebbles. Adult storm-petrels locate their burrows at night by a combination of smell—a sense that is highly developed in tube-nosed seabirds such as storm-petrels—and vocalizations given by members of a pair, both on the wing and in the nesting burrows. This enables pairs to recognize both their burrows and their mates.

A single white egg deposited in the nest chamber is incubated by both sexes for 41-42 days, with an additional 63-70 days required before fledging occurs. Fledging generally takes place in late summer or early fall (early September to early November), or even later for nests with particularly late egg-laying dates. Nest exchanges and the feeding of young occur after dark and are usually accompanied by an eerie cacophony of chuckles and purrings as adult storm-petrels communicate with one another during their comings and goings from the open sea. In the nest burrows the juveniles are fed an oily mixture of regurgitated stomach contents comprised of partially digested squid, euphausiid shrimp (krill), amphipods, small fish, and other planktonic organisms. Once the young fledge from the burrow in late summer or early fall, they will not return to land until reaching breeding age in 4 -6 years. The oldest known banded bird was at least 36 years old.

Little detailed life history information is available for Leach’s storm-petrels nesting in Massachusetts; however, existing data suggest that breeding adults return to previous season’s nest burrows as early as late April. By late spring nocturnal breeding activity is underway, with June 25 representing the earliest known egg date for Massachusetts. After nesting, Leach’s storm-petrels return to the open sea where they spend most of their lives. Data suggest that peak numbers of Leach’s storm-petrels in offshore Massachusetts waters occur in late August and early September; however, occasionally significant numbers are pushed inshore following prolonged Nor’easters in October and early November. Most Leach’s storm-petrels appearing during this late summer and early fall period emanate from large colonies located north of Massachusetts.

Population status

The most recent global population estimate is 6,700,000–8,300,000 mature adults. The population is likely evenly distributed between the Atlantic and Pacific. The global population trend is decreasing, with a recent study indicating a minimum 30% population decline. Historically, the introduction of predators across the species’ range (i.e. cats, dogs, mice, rats, pigs, and foxes), as well as mammals capable of habitat degradation (e.g. sheep), caused widespread population declines in the 19th and early 20th centuries. The International Union for the Conservation of Nature lists Leach’s storm-petrels as vulnerable.

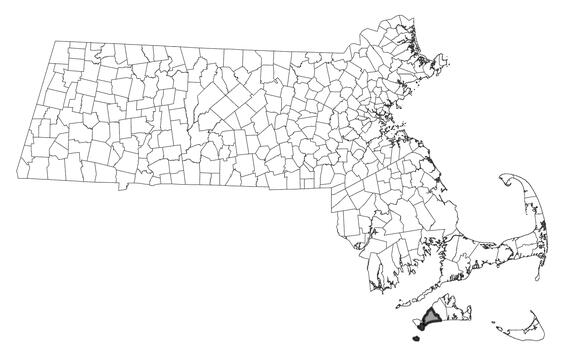

The Leach’s storm-petrel is classified as an endangered species in Massachusetts due to its extremely limited and declining breeding population in the Commonwealth, located at the extreme southern terminus of the species’ breeding range in the Atlantic Ocean. First discovered nesting in Massachusetts in 1933, the state’s population was initially estimated to include as many as 80-90 pairs. Numbers have steadily declined since, to the point where current breeding numbers in Massachusetts are suspected of being fewer than 15 pairs from the two known sites. This species is poorly known in Massachusetts. Potential causes for the decline in numbers include the tremendous increase in the numbers of predatory nesting herring and great black-backed gulls, habitat changes, human disturbance at the nest sites, and range-edge stochasticity. Historically, military practice bombing at one site undoubtedly limited the colony there.

Distribution and abundance

The Leach’s storm-petrel is a widespread seabird primarily confined as a breeder to the Northern Hemisphere in both Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Pacific populations breed on islands from Baja California to the Aleutian Islands, Alaska, and from Japan to the Commander Islands, Russia. Atlantic populations breed on scattered islands from Massachusetts north to Labrador, Newfoundland, Iceland, northern Scotland, and Norway. After breeding, Leach’s storm-petrels range widely at sea. They can be found in southern temperate waters in the eastern Atlantic and into the North Pacific tropics.

Distribution in Massachusetts. 1999-2024. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Leach’s storm-petrel breeding habitats require offshore islands far from predatory mammals with sufficient burrow soil or crevices among rocks. Pairs will also utilize anthropogenic structures (e.g. croft ruins in North Rona, Scotland; stone walls on Farallon Islands, California). Habitat types on offshore islands range widely, from talus fields to coniferous forests to open grass meadows.

Leach’s storm-petrels breed in Massachusetts on two tiny, low-lying offshore islands where they nest in colonies in stone retaining walls and burrows beneath beach debris. Other than when they come ashore to nest, Leach’s storm-petrels spend their entire life over the open ocean. In Massachusetts much of their time is spent over the continental shelf well away from land, where they are seldom observed. Though they occasionally appear close to shore during prolonged onshore coastal gales in the fall, they tend to shun the inshore summer fishing activities that ordinarily attract large numbers of Wilson’s storm-petrels.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Leach’s storm-petrel (Oceanodroma leucorhoa)

Threats

The largest threat and cause of mortality at breeding colonies is predation from both introduced and native predators. A brief list of predators includes introduced rats, cats, gulls, river otters, owls, corvids, peregrine falcons, and bald eagles. Leach’s storm-petrels main predator defense is vomiting oil.

Direct human threats to Leach’s storm-petrels are now minimal. Pesticides and related eggshell-thinning negatively impact breeding success. Oil spill impact is minimal compared to other seabird species, but ingestion of oil or oil-dispersants also negatively impacts breeding success. Leach’s storm-petrels are very prone to plastic ingestion, with plastic found in 5-48% of regurgitations depending on survey site. Light attraction is another significant concern, particularly from offshore drilling platforms. Nesting site competition from other burrow nesting species may negatively impact Leach’s storm-petrels, especially on sites where accidental damage to burrows from grazing mammals has occurred. Plastic trash in the environment poses a threat as it can be mistaken as food by seabirds and shorebirds and ingested or cause entanglement. Ingested plastics, common for seabirds, can block digestive tracts, cause internal injuries, disrupt the endocrine system, and lead to death. Entanglement from fishing gear and other string-like plastics can cause mortality by strangulation and impairing movements.

Strong onshore wind events throughout the Atlantic have stranded large number of Leach’s storm-petrels, placing them at risk of exposure.

Conservation

Leach’s storm-petrel are monitored at their North Atlantic and Pacific breeding colonies. Monitoring includes reproductive success, diet studies, adult survival, and, most recently, tracking studies focused on foraging and migration. Updated population estimates are needed, especially for the eastern Pacific colonies, and more research and surveying are needed to inform the population’s conservation status.

Conservation efforts should focus on removing introduced predators and reducing predation efforts from native predators. Additionally, reduced artificial lights at offshore oil platforms were successful in decreasing numbers of attracted and stranded Leach’s storm-petrels. These conservation initiatives should be included in offshore wind expansion. Avoid or recycle single-use plastics and promote and participate in beach cleanup efforts.

Efforts to minimize disturbances, reduce predation, and improve nesting habitat may help protect this species in Massachusetts. Global protection efforts for this species should probably focus on the large colony sites in Maine and eastern Canada.

Acknowledgments

Beach-nesting birds in Massachusetts are protected and managed by an extensive network of highly dedicated and conservation-minded landowners, individuals, organizations, and agencies. The birds’ successes are their successes.

References

Ainslie, J. and Atkinson, R. “On the breeding habits of Leach’s Fork-trailed Petrel.” British Birds. (1937): 234-248.

Alderfer, J. (Ed.). “National Geographic complete birds of North America.” 2006. National Geographic, Washington, D.C.

BirdLife International. “Species factsheet: Leach's storm-petrel Hydrobates leucorhous.” 2018.

Palmer, R. S. Handbook of North American birds. Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 1962.

Petersen, W. R. and W. R. Meservey. Massachusetts breeding bird atlas. Massachusetts Audubon Society, Distributed by University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst & Boston, 2003.

Pollet, I. L., A. L. Bond, A. Hedd, C. E. Huntington, R. G. Butler, and R. Mauck. “Leach's storm-petrel (Hydrobates leucorhous), version 1.1. In Birds of the World (Editor not available)”. 2021. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Sibley, D.A. The Sibley guide to birds. Alfred A. Knopf, New York, 2000.

Townsend, C. W. and F. H. Allen. Breeding of Leach’s Storm Petrel on Penikese Island. Auk 50 (1933): 426-427.

Contact

| Date published: | April 23, 2025 |

|---|