- Scientific name: Ixobrychus exilis

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Least bittern

The least bittern is a small, wading bird and member of the Heron (Ardeidae) family with a long neck and bill and a dark crown. Both sexes are similar in size. Length is 33 cm (13 in), wingspan is 43 cm (17 in), and weight is 80 g (2.8 oz [Sibley 2000, Gibbs et al. 2009]). Both the neck and sides are brown to orange and the front and neck have white stripes. Males have a black crown and back. In females, these are purple to dark brown (Sibley 2000, Gibbs et al. 2009). The song is a slightly descending, rapid poo poo poo, (Feith 2003) somewhat like that of a black-billed cuckoo (Forster 203), though the call of that species does not descend. The call is a loud, harsh quacking (rick-rick-rick) and in flight they make a short kuk or gik (Sibley 2000). They are most vocal at dawn (Forster 2003). Least bitterns are reported to sit or stand still on approach with necks and beaks raised to the sky, perhaps to blend in with tall vegetation (Forbish 1929, Harrison 1975).

Green herons are similar in size and coloring, but have a shorter neck, blue-gray back and wings, and brown neck and chest, a white chin, some yellow coloration on the face, and yellow legs. They also have some white striping on the breast. Green herons keep their necks close to the body, not extended as least bitterns do. Both male and female green herons have similar size and coloration (Davis and Kushlan 1994). Black-crowned night herons are slightly larger (length 58-66 cm [22-25 in]; wingspan 110 cm [44 in]). Adult night-herons have a short neck and a black bill. They also have a black cap and back, gray wings and the underside is white. Juveniles, however, have a gray back and cap and brown and white striped breast. Both adults and juveniles have red eyes and yellow legs (Davis 1993, Sibley 2000).

Life cycle and behavior

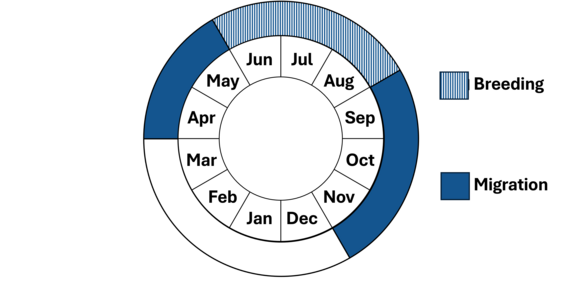

Phenology in Massachusetts. This is a simplification of the annual life cycle. Timing exhibited by individuals in a population varies, so adjacent life stages generally overlap each other at their starts and ends.

bitterns generally arrive at nesting areas in Massachusetts by mid to late May, and pairs form soon after (Forbush 1929, Forster 2003). Eggs and fledglings have been observed in Massachusetts throughout June (Forbish 1929, Forster 2003). Least bitterns construct a nest close to water within dense vegetation. The male constructs the nest in concealed areas high enough above the water level to avoid flooding. They pull and bend dead stalks to create a platform and then add other material to complete the nest (Forster 2003). Sometimes nests from previous year or nests of other birds are used (Weller 1961). A clutch of 4-5 blush or greenish eggs is laid over a six-day period and hatch in 17-20 days (Harrison 1975, Forster 2003). The emergence of aquatic insects in Massachusetts wetlands peaks in June when adults are feeding young. Young can fly in approximately 29 days but are able to forage much earlier.

Second broods have not been clearly documented (Gibbs et al. 2009), but the bitterns may breed again if their first attempt fails (Forbush 2003). Least bitterns build foraging platforms of bent reeds at feeding sites and use these to forage in deeper waters than their small size might allow them otherwise (Gibbs et al. 1995). They have not been observed frequently during fall migration but appear to migrate from late August to mid-September (Forbush 1929, Forster 2003), though this may extend to October. Young birds may remain near the nesting area longer and migrate later (Gibbs et al. 2009).

Least bittern adults and chicks are vulnerable to predation by various mammalian, avian, and reptilian predators including raptors, crows, raccoons, mink, snakes, snapping turtles, and bullfrogs.

Population status

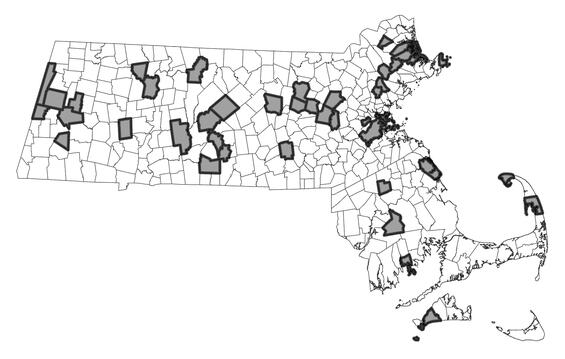

Least bitterns are reported as possible, probable or confirmed breeding in 12 blocks in the previous (2007-2011) Massachusetts Breeding Bird Atlas project, compared to 10 blocks in the 1975-1979 atlas (MassAudubon 2003-2010, USGS 2011), primarily at Plum Island and along the Sudbury River, though there are historic records in other locations prior to the 1950s (Veit and Peterson 2993). Least bitterns are secretive so that data from large-scale, standardized surveys, such as the North American Breeding Bird Survey cannot accurately determining status or population trends at state, regional, or national scales. However, specialized surveys that utilize call-playbacks can be quite effective in detecting the presence of this species.

Distribution and abundance

Least bitterns breed from southeastern Canada through the eastern and central U.S to Mexico and Costa Rica. This species is largely absent from the Appalachians. Least bitterns overwinter along the Atlantic Coastal Plain south to the Gulf Coast as well as Baja California and parts of Central America. Birds breeding in areas that are frost-free over the winter may not migrate (Gibbs et al. 2009).

Distribution in Massachusetts. 1999-2024. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Least bitterns inhabit freshwater and brackish marshes with dense, tall vegetation, particularly cattails (Typha spp.), sedges (Carex spp.), bulrush (Scirpus spp.), and arrowhead (Sagittaria spp.), interspersed with clumps of woody vegetation and substantial areas of open water. They will readily use impoundments that have associated wetlands (Gibbs et al. 2009). They have been more frequently found in marshes larger than 12.5 acres (> 5 ha; Brown and Dinsmore 1986). They generally nest alone but may form loose colonies or with nests in close proximity (Kushlan 1973, DeGraaf and Yamasaki 2001). Both pied-billed grebe and marsh wren use similar habitat. Green herons use wooded wetlands and nest in trees or shrubs.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Invasion of wetlands by Phragmites are the primary modern threat to breeding least bitterns in Massachusetts. Wakes from boats and jet skis may swamp nests. Climate change is adversely impacting wetland and marshes through changes in hydrology and sea level rise.

Conservation

Protection of suitable habitat is the priority for this species. Optimal habitat consists of shallow wetlands > 10 hectares (25 acres) with a dense growth of emergent vegetation, particularly cattails, and patches of open water. Wetlands need to be protected from siltation, chemical pollution and invasion by species that could alter vegetation composition, sedimentation and structure (Gibbs et al. 2009). Since structure can change with water depth, factors that affect water depth, such as inter-annual precipitation changes or alteration in the flow regime, may significantly influence habitat suitability at any given location within a wetland. Therefore, wetlands managed for Least Bittern should be both large and structurally diverse enough to provide a range of microhabitats to buffer possible effects of water level variation. Wetlands created by beavers may be important habitat, and beaver activity at the landscape scale may be an important factor in maintain annual access to suitable nesting habitat as conditions change.

Systematic monitoring is needed to determine changes in population status. Playback of calls at known and potential sites should be used to determine presence of least bittern. Further research in Massachusetts should focus on causes of nest failure, such as site disturbance or predation, as well as causes of adult and juvenile mortality.

References

Brown, M., and J.J. Dinsmore. 1986. Implications of marsh size and isolation for marsh bird management. Journal of Wildlife Management. 50 (3): 392-397.

Conway, C.J. 1995. Virginia Rail (Rallus limicola), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/173 doi:10.2173/bna. Accessed March 15, 2010.

Davis, Jr., W.E. 1993. Black-crowned Night-Heron (Nycticorax nycticorax), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/074 doi:10.2173/bna.74. Accessed March 15, 2010.

Davis, Jr., W.E., and J.A. Kushlan. 1994. Green Heron (Butorides virescens), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/129

doi:10.2173/bna.129. Accessed March 18, 2010.

DeGraaf, R.M., and M. Yamasaki. 2001. New England Wildlife: Habitat, Natural History, and Distribution. University Press of New England. Hanover, New Hampshire, USA.

Feith, J. 2003. Bird Song Training Guide. CD-ROM. Madison, WI.

Forbush, E.H. 1929. Birds of Massachusetts and Other New England States. Part I. Water Birds, Marsh Birds and Shore Birds. pp. 321-323. Massachusetts Department of Agriculture. Boston, MA.

Forster, R.A. 2003. Least Bittern, pp. 34-35 in Peterson, W.R. and W.R. Meservey (eds.) 2003. Massachusetts Breeding Bird Atlas. Massachusetts Audubon Society. Distributed by the University of Massachusetts Press, Amherst, MA.

Gibbs, J.P., F.A. Reid, S.M. Melvin, A.F. Poole, and P. Lowther. 2009. Least Bittern (Ixobrychus exilis), The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology; Retrieved from the Birds of North America Online: http://bna.birds.cornell.edu/bna/species/017 doi:10.2173/bna.17 (Accessed: February 13, 2010).

Harrison, H.H. 1975. A Field Guide to Birds’ Nests of 285 Species Found Breeding in the United States East of the Mississippi River. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston, MA.

Kushlan, J.A. 1973. Least Bittern nesting colonially. Auk 90 (3): 685-686.

MassAudubon 2003-2010. Massachusetts Breeding Bird Atlas 1. Available: http://www.massaudubon.org//birdatlas/bba1/index.php. Accessed February 13, 2010.

Sibley, D.A. 2000. National Audubon Society The Sibley Guide to Birds. Chanticleer Press, New York, NY.

USGS (United States Geological Survey) 2010. North American BBA Explorer: Massachusetts 2007-2011. Available: http://www.pwrc.usgs.gov/bba/index.cfm?fa=explore.ResultsSummary&BBA_ID=MA2007. Accessed February 13, 2010.

Veit, R.R., and W.R. Peterson. 1993. Birds of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Audubon Society.

Weller, M.W. 1961. Breeding biology of the Least Bittern. The Wilson Bulletin 73 (1): 11-35.

Contact

| Date published: | April 4, 2025 |

|---|