- Scientific name: Sternula antillarum

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Special Concern (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Least tern (Sternula antillarum)

The least tern measures 21-23 cm (8.3-9.1 in) in length and weighs 40-62 g (1.4-2.2 oz). In breeding plumage, the adult has a black cap and eyestripe, white forehead, pale gray upperparts, white underparts, a black-tipped, yellow-orange bill, and yellow-orange legs. Outside the breeding season, the crown and eyestripe become flecked with white, a dark bar forms on the wing, and the bill and legs darken. Hatchlings are white, tan, or buff with black speckles. Juveniles are brown and buff on the back; pale feather edgings give a scaly appearance. Underparts are white, the crown is buff speckled black, and the eyestripe and nape are blackish. The least tern’s voice is high and shrill. Its repertoire includes zwreep and kit-kit-kit-kit alarm calls, k’ee-you-hud-dut recognition call, and the male’s ki-dik contact call. Common (Sterna hirundo), roseate (Sterna dougallii), and Arctic (Sterna paradisaea) terns are all much larger, have entirely black foreheads and crowns in breeding plumage, have different colored bills and, proportionately, have much longer tails.

Life cycle and behavior

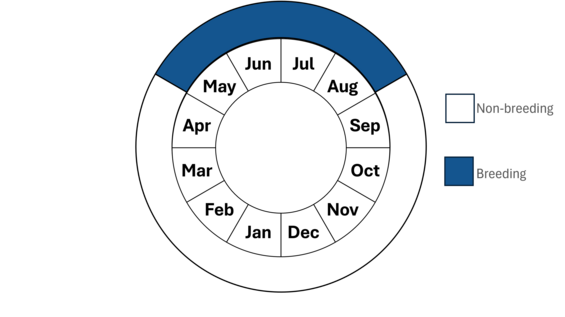

Phenology in Massachusetts. This is a simplification of the annual life cycle. Timing exhibited by individuals in a population varies, so adjacent life stages generally overlap each other at their starts and ends.

Least terns arrive in Massachusetts in early May. Colony formation and courtship quickly ensue. Egg laying commences 2-3 weeks after birds arrive and a couple weeks later than that of common and roseate terns: dates range from 20 May to 23 August. Incubation lasts about 3 weeks, as does the nestling period. The terns have mostly departed for winter locales by early September, and in some years by early August.

Colony. The least tern is gregarious and nests in colonies of just a few to >2000 pairs, but colonies usually number <25 pairs. In 2024, the largest colony in Massachusetts numbered about 700 pairs. In Massachusetts, the least tern often nests in association with the piping plover (Charadrius melodus), with which it shares similar nesting habitat requirements, but only rarely forms mixed colonies with other tern species.

Responses to predators and intruders. Within the colony, nesting is fairly synchronous as compared to that of Massachusetts’ larger terns; this may be a strategy to reduce the amount of time the least tern colony is vulnerable to predation. Least tern eggs and chicks are cryptically colored and hatched eggshells, the white inner side of which is conspicuous, are removed from the nest site. Colony-nesting seabirds, such as terns, benefit from group defense. When eggs and chicks are threatened, adults give alarm calls, dive, defecate on, and attack intruders. When adults are vulnerable (for instance, to canids), they desert the nest or fly high over the predator. Repeated intrusions by nocturnal predators, in particular, may cause the colony to desert the site. Shifts between different nesting sites within the breeding season in response to disturbance are common for this species. Terns become more defensive as the season progresses. Birds experienced with human intruders are more aggressive than inexperienced birds, and occasionally will even strike humans, earning the least tern the nickname, “little striker.”

Pair bond and parental care. The least tern is monogamous. In a California study, about half the birds retained the same mate for more than one year. Courtship behavior includes aerial and ground displays. In the aerial display, a fish-carrying male is chased by 1 to 4 other terns; the display ends in a stiff-winged glide, during which participants cross each other’s paths and bank towards each other repeatedly. Courtship on the ground includes parading and posturing. Males also feed females during courtship and throughout incubation. Incubating and chick-rearing duties are shared by both parents, but not equally: females typically do about 80% of the incubating, and more of the brooding/attending; males may do more feeding of chicks.

Nest. The nest, which is often just slightly above the high tide line, is a shallow scrape in the substrate to which vegetation, shell, or pebbles may be added. Considerable nest loss can be attributed to storms, given the low-lying nature of many nests. Mean inter-nest distance at a New Jersey colony was about 9 m (30 ft) by the end of incubation.

Eggs. Eggs are oval or sub-elliptical, and measure about 31 x 23 mm (1.2 x .91 in). Color and markings are very variable, but eggs generally have a beige or light olive-brown ground color with dark spots and splotches. Clutch size is two or (especially for interior least terns) three, sometimes one. Incubation, which is inconsistent until the clutch is complete, lasts about 23 on average days in Massachusetts.

Young. Chicks are semi-precocial. At hatching, they are downy and eyes are open. Parents brood chicks for the first 1-2 days, after which time chicks leave the nest and usually wander up to 200 m (~220 yards) from nest site (up to 1 km [.6 mi] in response to disturbance). Parents carry prey to chicks in their bills at a rate of about 2 fish/hour. While adults forage, chicks seek shelter in vegetation or near debris; older chicks may wait at the water’s edge. Fledging occurs after about 3 weeks. Young disperse from the natal site within 3 weeks of fledging and may still be fed by parents for up to 8 weeks after fledging. Family units are thought to migrate together.

Diet and foraging. The least tern primarily consumes small fish but also takes crustaceans and insects. The most common prey items in Massachusetts are sand lance, herring, and hake. This tern hovers 1-10 m (3-33 ft) over water, then plunges to the surface to capture prey. Insects are captured on the wing and by skimming the water surface. It may forage singly or in small flocks of 5-20 birds.

Demography and survival: Most least terns breed annually starting at 3 years, some at 2 years. One brood per season is raised, but least terns may renest up to 3 times if eggs or chicks are lost early enough in the season. Annual productivity, which is difficult to estimate because of the high mobility of chicks shortly after hatching and intermingling of fledged young from multiple colonies, is very variable, but was estimated at about half a chick per pair at several locations in the country. There are no data from Massachusetts, but elsewhere survival from fledging to 2-3 years was estimated at about 80%, and annual survival of adults was estimated at over 85%. The oldest documented wild least tern is a Massachusetts-hatched individual encountered dead at age 24 years.

Population status

The least tern suffered the same fate as Massachusetts’ larger terns at the end of the 19th century – they were slaughtered for use as decorations for hats. By the early 20th century, only about 250 pairs of least terns remained in the state. Following legal protection, numbers increased to the 1,500 pair level by the 1950s but declined again (perhaps because of increased recreational use of beaches) to perhaps 900 pairs by the early 1970s. More proactive protection of breeding colonies since then has contributed to an increase in numbers, although progress has not been steady (Figure 2). In 2024, approximately 4,318 pairs nested in the state. It is difficult to estimate least tern population sizes with precision due to the general instability of colonies and the tendency of birds that have lost nests to try again in the same year at other sites.

Distribution and abundance

The least tern is widely distributed in North America, with populations on the Atlantic, Gulf, and Pacific coasts, as well as along rivers and other wetlands in the interior of the continent. The least tern winters on the coasts of Mexico, Central America, and South America, south to northern Argentina. However, specific wintering areas for Atlantic and Gulf coast birds versus interior birds are uncertain.

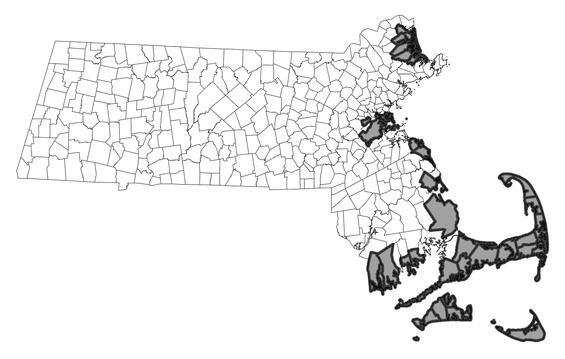

Nesting at 89 breeding sites in 2024, the least tern is Massachusetts’ most widely distributed tern. Favored breeding sites remain in flux due to the species’ sensitivity to disturbance, and because of its preference for nesting on unvegetated beaches, which are generally those that have received recent overwash.

Distribution in Massachusetts. 1999-2024. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

In Massachusetts, the least tern nests on sandy or gravelly beaches periodically scoured by storm tides, resulting in sparse or no vegetation; it also takes advantage of dredge spoils. In other areas of the country, it nests on riverine sandbars, mudflats, and gravel roofs. Along coasts, the least tern forages in shallow-water habitats, including bays, lagoons, estuaries, river and creek mouths, tidal marshes, and ponds. Foraging generally occurs close to the nesting site, and up to 3 km (1.9 mi) away from coastal colonies in response to an abundance of prey. At inland sites, least terns forage up to 12 km (7.5 mi) away from the colony.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Adult least tern with its two chicks

Threats

Habitat loss and degradation: Nesting habitat is threatened by development, shoreline hardening (which interferes with natural coastal processes), dune-building (which changes beach slope), rising sea levels, and increasing frequency and intensity of storms due to climate change.

Disturbance at nest sites. Colonies are regularly threatened by beach management activities such as beach raking, and human recreation, including pedestrians and their dogs, over-sand vehicles, and fireworks.

Predators. A wide variety of birds and mammals, crabs, and fish are predators of least tern eggs, chicks, and adults. Avian predators include crows, gulls, great blue heron, black-crowned night-heron, ruddy turnstone, sanderling, great horned owl, peregrine falcon, American kestrel, and northern harrier, among others. Mammalian predators include fox, coyote, raccoon, skunk, opossum, feral hog, cat, dog, and rat. Because in Massachusetts most least tern colonies are on mainland beaches accessible to both mammalian and avian predators, predation rates of eggs and chicks are high, contributing to frequent renesting and colony relocations.

Climate change: In addition to climate-induced habitat loss from rising sea levels and storms, ocean warming will result in shifts in least tern prey species’ distributions and changes in their abundances.

Wind farms: The construction and operation of offshore wind turbines may cause changes to prey availability, displacement from foraging habitat, and mortality from collisions.

Plastic: Plastic trash in the environment poses a threat as it can be mistaken as food by seabirds and shorebirds and ingested or cause entanglement. Ingested plastics, common for seabirds, can block digestive tracts, cause internal injuries, disrupt the endocrine system, and lead to death. Entanglement from fishing gear and other string-like plastics can cause mortality by strangulation and impairing movements.

Conservation

Since the 1970s, most sites have been fenced and posted with signs to discourage human intrusion into colonies. At many sites, least tern and piping plover protection and management is integrated due to the species' similar nesting habitat requirements and threats. Because of the least tern’s propensity for nesting on mainland and barrier beaches (in contrast to offshore islands), disturbance of colonies by humans and predators remains a chronic problem. The principal conservation challenge confronting wildlife managers in protecting least terns is to maintain adequate separation between people on the beaches and the nesting colonies to enable the birds to successfully reproduce. Restricting access to nesting areas through installation of post-and-string (“symbolic”) fencing is crucial. Humans and their dogs directly and indirectly harm nesting birds by: keeping adult birds off nests, contributing to egg and chick mortality due to environmental exposure and predation; stepping on eggs and chicks; and in the case of dogs, killing eggs and chicks. Over-sand vehicles crush tern eggs and chicks and destroy habitat; ruts created by tires trap chicks, preventing normal movements and further exposing them to interactions with vehicles. Garbage left on the beaches by humans may attract predators to colonies. Avoid or recycle single-use plastics and promote and participate in beach cleanup efforts. Given the habitat that the least tern selects, intensive and ongoing management of colonies will always be necessary to adequately shield them from disturbance. Efforts to limit coastal development and ensure that other coastal activities are conducted in a manner that does not harm terns or their habitat are also critical to protecting the viability of the state’s population.

Very little is known about wintering least terns. Before whole life-cycle conservation will be feasible, substantial research is necessary to locate birds on the wintering grounds, identify breeding population origins of wintering birds, and understand ecology and threats.

Acknowledgments

Beach-nesting birds in Massachusetts are protected and managed by an extensive network of highly dedicated and conservation-minded landowners, individuals, organizations, and agencies. The birds’ successes are their successes.

References

Bird Banding Laboratory. North American Bird Banding Program Longevity Records. Version 2023.2. Eastern Ecological Science Center. US Geological Survey. Laurel, MD.

Blodget, B.G., and S.M. Melvin. Massachusetts tern and Piping Plover Handbook: A Manual for Stewards. Westborough, MA: Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, 1996.

Thompson, B. C., J. A. Jackson, J. Burger, L. A. Hill, E. M. Kirsch, and J. L. Atwood (2020). Least Tern (Sternula antillarum), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole and F. B. Gill, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Veit, R.R., and W.R. Petersen. Birds of Massachusetts. Lincoln, MA: Massachusetts Audubon Society, 1993.

Contact

| Date published: | April 24, 2025 |

|---|