- Scientific name: Myotis lucifugus

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Little brown bat (Myotis lucifugus)

The little brown bat (or little brown myotis) has glossy brown fur, varying in tone from dark brown to reddish brown to golden brown to olive. On its back, the hairs are two-toned, appearing dark at the base and light at the tip. On its underside, the fur is lighter and tipped with buff. The bat’s face is furry, with only the nostrils and lips bare. The little brown bat averages 60-102 mm (2.4-4.0 in) in total length, with a tail of 31-41 mm (1.2-1.6 in). Its weight in summer averages 4.5 g (0.16 oz), but as winter approaches, the bat accumulates fat, and before hibernation, its average weight approaches 7.5-8.5 g (0.26-0.3 oz). This widely distributed, once-common bat is found in a variety of habitats, including human habitations.

Similar species: The big brown bat is the only other bat commonly found in houses. It is larger in size than the little brown bat, with a forearm length exceeding 44 mm (1.7 in), and the forearm of the little brown bat measuring 36-40 mm (1.4 -1.6 in). It has a broader nose and less furry face. The rare Indiana bat is also similar in appearance, but it has a keeled calcar (a ridge of cartilage between the foot and the tail), which the little brown bat lacks. The little brown bat can be distinguished from other species in Massachusetts by its bicolored fur, hairless interfemoral membrane (the skin stretching between the legs and tail), lack of a black face mask (which the small-footed myotis has), and ears which do not extend more than 4 mm (0.2 in) beyond its nose when laid forward (which the northern long-eared bat has).

Life cycle and behavior

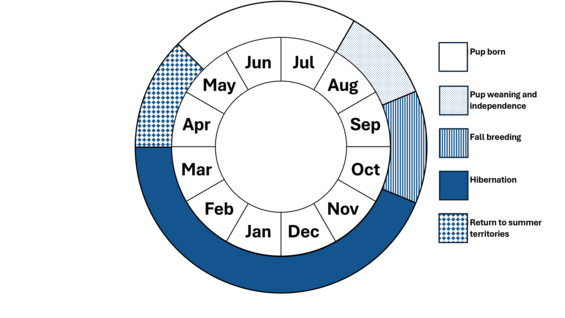

In the summer months, little brown bats emerge at dusk from daytime roosts for the first in a series of night-time flights. Little brown bats use echolocation to locate the insects on which they feed, often catching them in their tail or wing membranes. By the end of summer, the bats have accumulated stored fat, often comprising up to 45% of their body weight. They begin to “swarm” around the entrances of caves and are thought to be testing the air of possible hibernacula. By the end of October, the bats enter hibernation sites. Their metabolisms slow and they enter torpor, rousing occasionally through the winter to drink water. Little brown bats may migrate long distances between winter and summer habitats. Individuals banded in breeding colonies in Massachusetts have been found hibernating at sites in Vermont and Connecticut up to 270 km (168 mi) away.

Female bats congregate and tend to remain separate from males, except during breeding. Breeding occurs in the fall during swarming, and inactive sperm are stored by the females until spring, when eggs are fertilized. A second mating sometimes occurs in the spring, with males mating with torpid females before they have emerged from their winter quarters. Females bear single young in mid-June to early July. The new, nearly naked babies are not carried with the mother, but remain at the roosting site, where they continue to grow and develop. Young bats make their first flight at around three weeks of age and reach adult size and leave the roost site at around four weeks old. The longevity record for the little brown bat is over 31 years; records of bats over 10 years old are common.

Population status

The little brown bat is listed as endangered under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act. All listed species are protected from killing, collecting, possessing, or sale and from activities that would destroy habitat and thus directly or indirectly cause mortality or disrupt critical behaviors. In addition, listed animals are specifically protected from activities that disrupt nesting, breeding, feeding, or migration.

Once the most abundant bat species in the northern United States, the little brown bat has been devastated by white-nose syndrome. Infected hibernacula in the Northeast have seen catastrophic losses of 90-100% of the population. White-nose syndrome is caused by a fungus, Pseudogymnoascus destructans, a species new to science, but closely related to fungi that naturally grow in caves. The fungus grows over bats while they hibernate, causing them to frequently rouse from dormancy losing valuable stored fat, and then failing to survive the winter. The fungus is believed to be passed from cave to cave primarily by the movements of breeding male bats, but human transport is also thought to be responsible for its original introduction from European caves and for its spread between some North American hibernacula.

Distribution and abundance

Little brown bats are found across the United States, north into southern Alaska and Canada, and south into the higher elevation forests of Mexico. Across the northern part of their range, they were historically the most abundant bat species. They were also common across much of the south, though absent from parts of southern California, the Great Plains, Florida, and coastal North Carolina and Virginia.

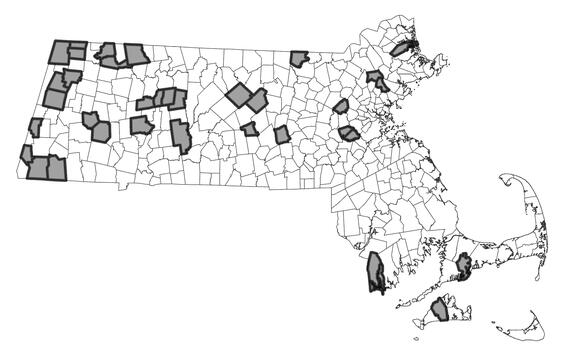

In Massachusetts, little brown bats occur statewide and have been identified in 274 of 351 municipalities in 13 of 14 counties.

Distribution in Massachusetts, 1999-2024 based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

During the warmer months, breeding females come together to form maternity colonies that can include over a thousand adults. In Massachusetts, these colonies are most often found in old barns and similar structures. Little brown bat males and non-breeding females occupy day and night roosts in small caves, buildings, trees, under rocks, and in piles of wood. Little brown bats are most commonly found in the evening foraging along forest roads, trails, and water bodies in forest-dominated landscapes. However, they can be found wherever flying insects are abundant. In winter, little brown bats hibernate in limestone caves, abandoned mines, and old aqueducts, where humidity is high, and temperatures rarely drop below freezing. Winter hibernacula (hibernation sites) have been reported in Berkshire, Franklin, Hampden, Middlesex, and Worcester counties.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

White-nose syndrome poses the greatest threat to the long-term security of the little brown bat. Fortunately, there is evidence that the few remaining individuals in the most severely impacted hibernation sites have a level of immunity, and their numbers are very slowly increasing. It also appears that the bats in some of the largest maternity colonies are hibernating outside of Massachusetts in sites less affected by white-nose syndrome. Fortunately, this means that some of the summer maternity colonies in Massachusetts are still strong. Summer habitat availability is not a limiting factor in Massachusetts.

Conservation

The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service is working in concert with government and non-profit groups to understand the spread of the fungus and potential for stopping its spread. Access to suitable, undisturbed hibernacula is essential to the survival of the little brown bat, and protection of known sites is paramount. Human disturbance of hibernacula can be discouraged or prevented with the use of gated entrances, in order to avoid arousal of hibernating bats and the spread of fungal spores.

In Massachusetts, it is unlawful to deliberately kill any species of bat. However, it is lawful to evict a colony of bats from a home, or other structure, during periods when, or where, they are not hibernating, or they are not caring for babies that are too young to fly. This means that colonies should only be evicted in May or from the first of August to mid-October (MassWildlife 2020).

References

Davis, W.H., and H.B. Hitchcock. 1965. Biology and migration of the bat, Myotis lucifugus in New England. Journal of Mammalogy 46 (2): 296-313.

MassWildlife. 2020. Homeowner’s Guide to Bats. Massachusetts Department of Fisheries & Wildlife: Westborough, MA. 26 pp.

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. 2012. “White-nose Syndrome.” http://whitenosesyndrome.org/

Whitaker, J.O., Jr. and W.J. Hamilton, Jr. 1998. Mammals of the Eastern United States, Third Edition. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY. 583 pp.

Contact

| Date published: | March 4, 2025 |

|---|