- Scientific name: Somatochlora linearis

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Special Concern (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Male mocha emerald

The mocha emerald (Somatochlora linearis) is a large, slender insect of the order Odonata, sub-order Anisoptera (the dragonflies), and family Corduliidae (the emeralds). Most striped emeralds (genus Somatochlora) are large and dark with at least some iridescent green coloration, brilliant green eyes in the mature adults (brown in young individuals), and moderate pubescence (hairiness), especially on the thorax. The mocha emerald is distinctive among the Somatochlora of Massachusetts in completely lacking markings on the thorax. The face is mostly yellowish brown with a brown band across the middle with a metallic green forehead (frons). The large eyes, which meet at a seam on the top of the head, are brilliant green in mature adults. The thorax is a mocha color with metallic green highlights. The cylindrical abdomen is most narrow at the base, widening to segment four and then narrowing slightly toward the distal end. The abdomen is black with a brownish yellow lateral spot at the proximal end of segments three through ten. The first segment has a large brownish yellow spot also positioned laterally and proximally. The wings of this species are transparent, though washed with brown or amber color, usually more extensive in females.

Adult male mocha emeralds range from 58.5 to 61 mm (2.3 to 2.4 in) in length. Females range from 65.5 to 68 mm (2.6 to 2.7 in) in length. Both sexes are similar in coloration and body form. Final instar nymphs range from 18 to 24mm (0.7 to 0.95 in) in length (Tennessen 2019).

Mocha emeralds can be distinguished from the other ten species Somatochlora recorded in Massachusetts by the complete lack of thoracic markings, elongate body form (especially in the females), and the abdominal spotting described above. However, definitive identification requires examination of the male’s distinctive ventral spine in the terminal abdominal appendages or the female’s thorn-shaped vulvar lamina (subgenital plate) oriented perpendicular to the abdomen (Lam 2024). Determination of these features usually require species in-hand accompanied by a hand lens or macro camera lens. Williamson’s emerald (S. williamsoni) and clamp-tipped emerald (S. tenebrosa) distributions overlap and are morphologically similar to mocha emerald and can be distinguished from the mocha emerald by their pale thoracic stripes and by their distinctive male terminal abdominal appendages and female vulvar lamina (Needham et al. 1999).

The nymphs and exuviae can be distinguished by characteristics as per the keys in Needham et al. (2000), Soltesz (1996), and Tennessen (2019).

Male (left) and female (right) mocha emeralds.

Life cycle and behavior

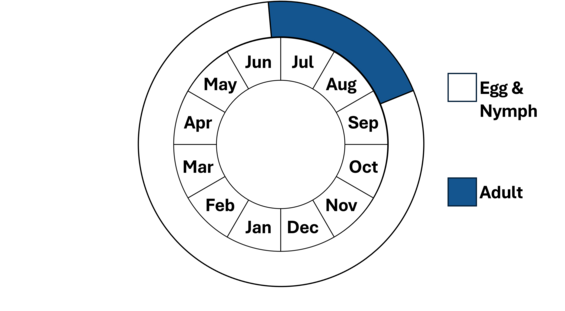

Note, nymphs are present year-round.

As with other Odonates, mocha emerald goes through aquatic egg and nymph life stages, and a terrestrial adult stage. The cryptic nymphs are predators, feeding on a wide variety of aquatic insects, small fish, and tadpoles. Nymphs undergo several molts (instars) for at least 2 years until they are ready to emerge as winged adults. Nymphs emerge up onto emergent vegetation, exposed banks, or tree trunks. When the nymph reaches a secure substrate, the adult begins to push itself out of the exoskeleton. As soon as the abdomen and wings are fully expanded, the adult takes its first flight. This maiden flight usually carries the individuals up into surrounding forest or other areas away from water, where they spend several days maturing and feeding and are somewhat protected from predation and inclement weather. Mocha emeralds can be found in fields and forest clearings foraging on small aerial insects, such as flies and mosquitoes, which are consumed while flying. The species is most active during mornings and evenings and is known to join feeding swarms with mosaic darners and other striped emeralds at dawn and dusk. When at rest, especially during midday, mocha emeralds hang vertically or perch obliquely from tree or shrub branches. After about a week, the adult coloration is acquired, and the dragonfly becomes sexually mature before returning to the breeding habitat to initiate mating.

Breeding in Massachusetts probably occurs from early July through August, as in other regions where this species occurs. Males patrol up and downs just above streams in search of females and driving off competing males. A joined male-female pair quickly flies off into the surrounding upland habitat to mate. Following mating, oviposition (egg-laying) occurs. Mocha emerald females are known to prefer to oviposit in shallow portions of the stream where the substrate is fine gravel or sand. Females fly back and forth over such an area tapping the substrate or water with the tip of her abdomen depositing eggs. Due to the shallowness of these areas, they may dry up soon after oviposition occurs. For this reason, eggs must be able to survive periods of drought.

Mocha emerald adults first appear in late June, peak in July and August, and are on the wing into early September.

Distribution and abundance

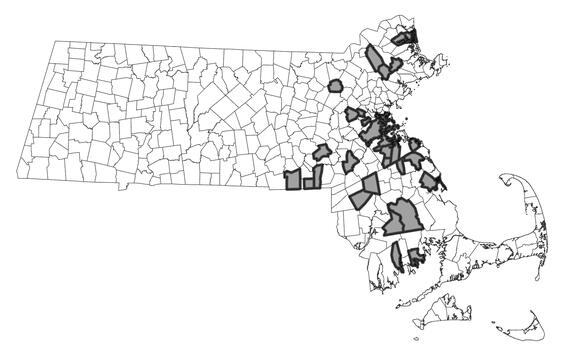

The mocha emerald is distributed throughout the eastern United States from Massachusetts south to Florida and west to Michigan, Iowa and Texas. In New England, the mocha emerald is recorded from Connecticut and Rhode Island, north only to Massachusetts. In Massachusetts, mocha emerald inhabits eastern parts of the state, specifically in the Parker, Ipswich, Concord, Mystic, Charles, Blackstone, and Taunton Rivers, and smaller coastal watersheds. The limited distribution to eastern Massachusetts may be in part due to its northern range limit, survey effort, and habitat suitability. Mocha emeralds are typically found in low abundance but can found in higher abundances in feeding swarms.

The mocha emerald is listed as a species of special concern in Massachusetts. As with all species listed in Massachusetts, individuals of the species are protected from take (picking, collecting, killing) and sale under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

In Massachusetts, the mocha emerald has been found most often away from breeding habitats in fields and forest clearings. However, many of these areas are adjacent to habitats that, based on observations elsewhere in this species’ range, are appropriate breeding sites for the mocha emerald. Breeding sites and nymphal habitat for this species are low gradient intermittent and perennial small-sized streams with mud, sand, and fine gravel substrates that flow through woods or swamps. Individuals have also been observed patrolling over seasonally intermittent open pools along powerline corridors or dirt roads.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Typical stream habitat for mocha emerald.

Threats

Threats to mocha emerald include degradation to water quality from run-off like salt, pesticides and herbicides, discharge of industrial and chemical pollutants, accelerated eutrophication, and loss of upland and riparian forests also needed for adult development. Mocha emerald may also be vulnerable to anthropogenically-induced streamflow alteration, such as water withdrawals and damming. More severe drought via climate change may pose a threat for mocha emerald considering its habitat are small streams with intermittent to perennial flows.

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

Surveys should target known sites and new streams and wetlands to inform mocha emerald occupancy and population status in Massachusetts. Surveys for adults are likely to be more effective for detection compared to nymph or exuvia as this life stage is extremely difficult to find. Adult surveys should target breeding and feeding habitats, including swarms, where detection might be most probable. Multiple site visits (e.g., ≥3) are likely required to detect this species because of its rarity and the difficulty to capture by net or camera. Sites with breeding evidence should be monitored every 5 years to document changes in occupancy and habitat conditions. Sites without breeding evidence require additional survey effort to conform breeding and nymphal habitat. Suitable stream and wetland habitat likely exists across the landscape as more sites have been identified in recent years. Effort should be devoted to surveys in new potential sites to further update mocha emerald status in Massachusetts.

Management

Upland and wetland protection to maintain water quality and quantity is critical for the conservation of mocha emerald. Protection of forested upland borders of these river systems are critical in maintaining suitable water quality and are critical for feeding, resting, and maturation. Development of these areas should be discouraged, and the preservation of remaining undeveloped uplands should be a priority. Alternatives to commonly applied road salts should tested to minimize freshwater salinization.

Research needs

Research effort is needed to estimate occupancy and detection rates for this species as it likely inhabits other sites not previously surveyed and species detection is likely low. Further refinement is needed to identify species habitat requirements including flow regimes as this species seems to occupy a range of flows from streams to swamps. Species distribution models coupled with climate change projections are needed to help assess future species risk and identify climate-resistant stream and wetland sites.

References

Dunkle, Sidney W. Dragonflies Through Binoculars. Oxford University Press, 2000.

Lam, E. Dragonflies of North America. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2024.

Needham, J.G., M.J. Westfall, Jr., and M.L. May. Dragonflies of North America. Scientific Publishers, 2000.

Nikula, B., J.L. Ryan, and M.R. Burne. A Field Guide to the Dragonflies and Damselflies of Massachusetts. 2nd ed. Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, 2007.

Paulson, D. Dragonflies and Damselflies of the East. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Soltesz, K. Identification Keys to Northeastern Anisoptera Larvae. Center for Conservation and Biodiversity, University of Connecticut, 1996.

Tennessen, K. Dragonfly Nymphs of North America: An identification guide. Springer, 2019.

Walker, E.M. 1958. The Odonata of Canada and Alaska, Vol. II. University of Toronto Press.

Contact

| Date published: | March 7, 2025 |

|---|