- Scientific name: Pieris oleracea

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Threatened (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Mustard white (Pieris oleracea), spring form, underside

The mustard white (Pieris oleracea) is a pierid butterfly with a wingspan of 37-45 mm (1.5-1.8 in). The wings are white with a small yellow spot at the humeral angle of the hind wing. In the spring brood, the underside of the hind wing has gray to black scales outlining the wing veins. Outlining of the veins is faint, almost absent, in later broods. The wings are unmarked above except for a small amount of gray to black shading along the costa and at the apex of the forewing. The West Virginia white (Pieris virginiensis) flies in spring, but compared to the spring brood of the mustard white, the outlining of the veins on the underside of the hind wing is lighter gray and more diffuse. A third species in the genus Pieris in Massachusetts is the common and widespread cabbage white (Pieris rapae); the upper side of the forewing of this species has two black dots and black apical shading.

Spring form, upper side

Summer form, underside

Life cycle and behavior

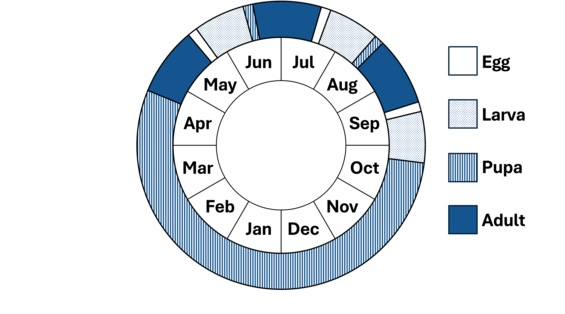

In Massachusetts, the spring brood of the mustard white flies from late April through late May. A second brood peaks in early July, and a third brood flies in late August and early September. In some years, the third brood is partial; in other years it is larger, and some individuals may represent a fourth brood. Adult butterflies imbibe nectar from their larval host plants and a wide variety of other flowers. Larvae feed on twin-leaved toothwort (Cardamine diphylla), cuckoo flower (Cardamine pratensis), watercress (Nasturtium spp.), and other mustard family plants (Brassicaceae). The chrysalis is attached to a plant stem just above the ground, and this stage overwinters.

Distribution and abundance

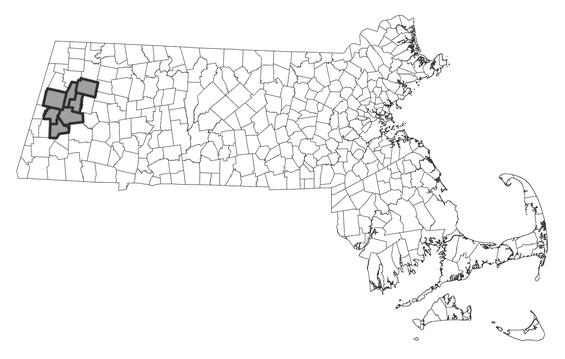

Massachusetts is at the southernmost extent of the mustard white’s range in eastern North America. Its range extends north to Newfoundland and Labrador and west to British Columbia and the Northwest Territories of Canada (Opler 1999). In Massachusetts, the mustard white occurs in Berkshire County.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

In Massachusetts, the mustard white inhabits openings in mesic forest, including riparian floodplains, margins of fens and marshes, and stream sides, as well as wet meadows, fields, and pastures.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Wet meadow in April with cuckoo flower (Cardamine pratensis) starting to bloom, habitat for the mustard white butterfly. Habitat managed by MassWildlife at George L. Darey Housatonic Valley WMA.

Threats

In Massachusetts, the mustard white butterfly has declined dramatically during the past 150 years. This decline is probably the cumulative result of several interacting factors (Keeler et al. 2006): the loss of intact woodland and wet meadow habitats and their associated flora of native crucifers (Chew 1981); introduction of the invasive garlic mustard (Alliaria petiolata) (Courant et al. 1994); and parasitism by the introduced braconid wasp, Cotesia glomerata (Benson et al. 2003). Female butterflies will lay eggs on garlic mustard, despite the fact that larval growth is typically slow, and survivorship poor, on this plant (Courant et al. 1994). There is some evidence, however, that the mustard white may be adapting toward more effective use of garlic mustard as a larval host (Keeler & Chew 2008). In addition, the cuckoo flower used by Massachusetts populations of the mustard white is an introduced variety, but larval growth is fast, and survivorship high, on this plant. C. glomerata, an introduced braconid parasitoid of the introduced cabbage white butterfly, has been shown to not only parasitize caterpillars of the mustard white, but even to prefer them over those of the cabbage white (Van Driesche et al. 2003). Other potential threats to the mustard white in Massachusetts include hydrologic alteration (where floodplain and wetland edge habitat are maintained by flooding), riverbank stabilization, other introduced generalist parasitoids, aerial insecticide spraying, non-target herbicide application, excessive browse of larval host plants by deer, and off-road vehicles. The mustard white is vulnerable to climate change, as it is a boreal species at the southern edge of its range in Massachusetts.

Conservation

Land protection and habitat management are the primary conservation needs of the mustard white in Massachusetts. In particular, openings in mesic forest such as riparian floodplains, margins of fens and marshes, and stream sides, and wet meadows, fields, and pastures should be conserved, restored, and managed to maintain habitat for this species and other species dependent on such habitats.

Survey and monitoring

The distribution of the mustard white in Massachusetts is well documented. Known populations should be surveyed to document persistence at least once every 25 years; every 10 years is more desirable when practicable.

Management

Management of floodplains, wetland edges, and wet meadows, fields, and pastures benefits a diversity of species. Restoration and maintenance of natural hydrology and control of invasive exotic plants are of primary importance. Habitat condition should be monitored and management adapted as needed.

Research needs

The natural history and conservation needs of the mustard white are well studied. However, the future effects of a warming climate on this species will likely be detrimental, and this should be monitored and documented.

References

Benson, J., R.G. Van Driesche, A. Pasquale, and J. Elkinton. 2003. Introduced braconid parasitoid and range reduction of a native butterfly in New England. Biological Control 28: 197-213.

Chew, F.S. 1981. Coexistence and local extinction in two pierid butterflies. American Naturalist 118(5): 655-672.

Courant, A.V., A.E. Holbrook, E.D. Van der Reijden, and F.S. Chew. 1994. Native pierine butterfly (Pieridae) adapting to naturalized crucifer? Journal of the Lepidopterists’ Society 48(2): 168-170.

Keeler, M.S., F.S. Chew, B.C. Goodale, and J.M. Reed. 2006. Modelling the impacts of two exotic invasive species on a native butterfly: top-down vs. bottom-up effects. Journal of Animal Ecology 75: 777-788.

Keeler, M.S. and F.S. Chew. 2008. Escaping an evolutionary trap: preference and performance of a native insect on an exotic invasive host. Oecologia 156: 559-568.

Layberry, R.A., P.W. Hall, and J.D. Lafontaine. 1998. The Butterflies of Canada. University of Toronto Press, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. 280 pp.

Opler, P.A. 1999. A Field Guide to Western Butterflies. Peterson Field Guide Series. Second edition. Houghton Mifflin, Boston, Massachusetts. 540 pp.

Van Driesche, R.G., C. Nunn, N. Kreke, B. Goldstein, and J. Benson. 2003. Laboratory and field host preferences of introduced Cotesia spp. parasitoids (Hymenoptera: Braconidae) between native and invasive Pieris butterflies. Biological Control 28: 214-221.

Contact

| Date published: | March 24, 2025 |

|---|