- Scientific name: Eubalaena glacialis

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

- Endangered (US Endangered Species Act)

Description

The North Atlantic right whale has been known in recent years to reach lengths of about 14 m (45 ft) and weigh 45 to 54 metric tons (50 to 60 tons), but larger animals up to 55 ft and 70 tons have been previously documented. This rotund baleen whale has a stocky, black body, lacks a dorsal fin, and has a characteristic V-shaped blow. The head is about one third of the length of the entire body. The top jaw of the mouth is lined with about 200-270 baleen plates (SNMNH 2025) measuring up to 3 m long (10 ft; NARWC 2025). Each plate is fringed with fine hairs on the inside. The species has callosities (raised patches of rough skin) on the top of their heads, on their chins, above their eyes, and behind their blowholes. Amphipods, also known as whale lice, colonize the callosities of North Atlantic right whales, sometimes giving their heads a yellowish-white patchy appearance (NEA 2025). Whale lice are symbionts that feed on sloughed whale skin and damaged tissue.

Life cycle and behavior

North Atlantic right whales have the potential to live past 50 years of age; however, a recent study found that life spans are often cut much shorter due to current anthropogenic threats (Breed et al. 2024). The median life span of individuals studied is just over 20 years with only a small portion (10%) approaching 50 years in age. Females can reach sexual maturity by the age of 10 but, in recent years, reproductive females seem to be giving birth for the first time at older ages (up to 20 years old; NOAA 2025). Gestation is estimated to last between 1 and 2 years with females usually giving birth about once every three years. However, calving intervals (timing between subsequent births) in recent years have increased to 6-10 years likely due to stresses associated with entanglements and injuries. A calf can be up to 4.3 m (14 ft) long at birth.

North Atlantic right whales are seasonal visitors to Massachusetts coastal waters, primarily in winter and spring in Cape Cod Bay, the Outer Cape and Massachusetts Bay, where up to 2/3 of the entire population is observed annually (CCPS 2022, Linden 2024, Pettis and Hamilton 2025). They feed on dense aggregations of zooplankton both at depth and at the surface. North Atlantic right whales can sometimes be seen from Massachusetts’ beaches feeding at the surface of the water, swimming through patches of zooplankton with their mouths open.

Changes to migration patterns

Climate change may be altering right whale migration patterns (Staudinger et al. 2024). For example, North Atlantic right whales appear to be arriving in Cape Cod Bay earlier each year. One study found that right whales arrived 40 days earlier each late-winter/early spring between 2008-2011, though results varied (the trend reversed the last two years of the study); this may be due to warming conditions in the northwestern Atlantic Ocean (Charif et al. 2020). Another study found a similar pattern; earlier spring transition dates have driven earlier movements between habitats from 1998-2017, indicating that North Atlantic right whales may respond to temperature to start migration to Cape Cod Bay (Ganley et al. 2022). Peak habitat use of North Atlantic right whales in Cape Cod Bay shifted 18.1 days earlier from 1998–2018 and was negatively related to the earlier onset of spring in the Gulf of Maine (Pendelton et al. 2022). North Atlantic right whales are also staying in Cape Cod Bay later in the spring season, albeit with high interannual variability (Pendelton et al. 2022). Shifts in annual and seasonal migration patterns of North Atlantic right whales have been linked to changes in the distribution and availability of their primary copepod prey, Calanus finmarchicus (Pershing et al. 2021).

Population status

The North Atlantic right whale is listed as endangered under both the federal and Massachusetts Endangered Species Acts. From the early 1500s to the 1920s, these whales were extensively hunted in the western North Atlantic. A full prohibition on whaling began in 1935, but today, North Atlantic right whales are struggling to recover due to incidental entanglements and vessel strikes, the leading causes of mortality for this species. According to the 2023 population estimate, there are about 370 individuals remaining, with fewer than 70 reproductive females (NOAA 2025). At this time, population growth is still below levels needed for species recovery (Linden 2024).

Distribution and abundance

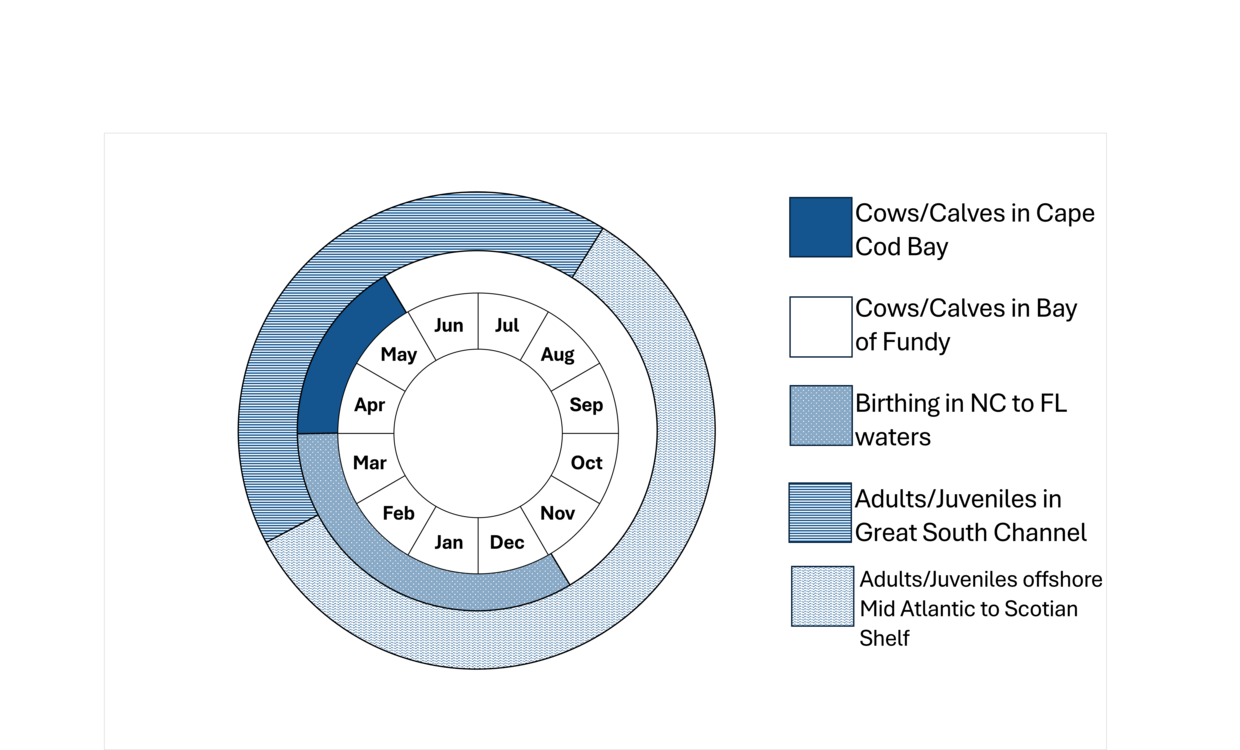

North Atlantic right whales inhabit the North Atlantic Ocean and are usually sighted in habitats along the eastern seaboard of North America between the Gulf of St. Lawrence in Canada to northern Florida in the United States. Different parts of their range are used for different purposes, including distinct feeding and calving areas. They primarily inhabit coastal and shelf waters, moving to higher latitudes during the spring and summer. In the western North Atlantic, aggregations of right whales are primarily found seasonally in 5 high use areas, including (1) the Gulf of St. Lawrence, Canada, (2) Roseway Basin off southern Nova Scotia, Canada, (3) Cape Cod and Massachusetts Bays, (4) Southern New England, and (5) off the coast of the southeastern United States, primarily Florida and Georgia (NOAA 2025). Few North Atlantic right whales remain in Massachusetts waters throughout the summer. Pregnant females, migrate to waters off the coast of Georgia and Florida to calve in the winter. Other females and males spend time throughout the rest of the year in the mid-Atlantic, and Southern New England, Cape Cod Bay, and other unidentified areas.

Approximate representation of the North Atlantic right whale's range (Image: NOAA/Fisheries)

Habitat

Cape Cod Bay, the Outer Cape and Massachusetts Bay are important feeding grounds for the species because of the dense concentrations of zooplankton that tend to occur in these habitats seasonally. However, the Gulf of Maine is warming faster than other marine habitats (Staudinger et al. 2024). Consequently, prey availability has been decreasing (Staudinger et al. 2024 and references therein).

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Currently, vessel strikes and entanglement in fishing gear are the two main causes of serious injury and mortality for North Atlantic right whales. Right whales are particularly vulnerable to vessel strikes because they spend time near or just below the water’s surface while feeding, socializing, and traveling. Furthermore, an estimated 85% of right whales have become entangled in fishing gear at least once (NOAA 2025). Federal and state regulations have been implemented to minimize the risk of these impacts, including speed restrictions, fishing gear modifications, and seasonally closed fishing areas.

Climate change is also posing a threat to right whales (Staudinger et al. 2024). Shifts in the distribution of marine mammals are largely attributed to the indirect effects of climate change, as prey availability, abundance, and quality are altered due to ocean warming and acidification. Planktivorous species like North Atlantic right whales, depend on seasonally reliable concentrations of highly nutritious and lipid-rich Calanoid copepods. Notably, increasing sea surface temperatures are negatively affecting cold-adapted subpolar copepod species, including Calanus finmarchicus through decreased growth, productivity, and shifts in overwintering phenology schedules (Staudinger et al. 2019; Staudinger et al. 2020; Pershing et al. 2021). In some instances, North Atlantic right whale spatial use patterns are shifting in response to changes in the distribution of their prey, and these shifts can put right whales in areas that lack protection from ship strikes and fishing gear entanglements (Record et al. 2019, Meyer-Guthrod et al. 2021).

Conservation

Conservation actions are prioritizing addressing threats to North Atlantic right whales associated with vessel strikes and entanglement in fishing gear. Federal and state regulations to minimize these impacts to right whales have been implemented through the Atlantic Large Whale Take Reduction Plan, the Ship Strike Reduction Rule, and various state conservation measures. In Massachusetts waters, commercial fixed-gear fisheries are required to remove gear in winter and spring when right whales are present. They are also required to use reduced breaking strength buoy lines (< 1,700 lbs) to reduce the risk of injury caused by potential entanglements. In addition, vessel operators are required to reduce their speed (<10 knots) seasonally when operating within certain habitats (e.g., Cape Cod Bay, Off Race Point, Great South Channel) when whales are likely present. Additional information on large whale conservation, including right whale conservation plans and measures, can be found on the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries webpage: Conservation of protected marine species.

Consistent and expanded monitoring of North Atlantic right whales is underway to better track this species over time and space throughout their range. However, reporting of all right whale sightings is important for their conservation. Live, dead, or entangled right whales should be reported immediately to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s hotline at 866-755-6622.

References

Breed GA, Vermeulen E, and Corkeron P. 2024. Extreme longevity may be the rule not the exception in Balaenid whales. Science Advances 10(51): DO10.1126/sciadv.adq3086.

Charif RA, Shiu Y, Muirhead CA, Clark CW, Parks SE, and Rice AN. 2020. Phenological changes in North Atlantic right whale habitat use in Massachusetts Bay. Global Change Biology 26(2):734-745.

CCS [Center for Coastal Studies – Provincetown]. 2022. Rare North Atlantic right whales return to Cape Cod Bay just as CCS team begins its field season. Available at: Rare North Atlantic Right Whales Return to Cape Cod Bay Just as CCS Team Begins Its Field Season | Center for Coastal Studies. Accessed on 6/16/25.

Ganley LC, Byrnes J, Pendleton DE, Mayo CA, Friedland KD, Redfern JV. Turner JT, Brault S. 2022. Effects of changing temperature phenology on the abundance of a critically endangered baleen whale. Global ecology and conservation 38:e02193.

Linden DW. 2024. Population size estimation of North Atlantic right whales from 1990-2023.NOAA technical memorandum NMFS NE. 324p. Available at: https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/66179.

Meyer-Gutbrod EL, Greene CH, Davies K.T.A., Johns DG. 2021. Ocean regime shift is driving collapse of North Atlantic Right Whale population. Oceanography 34(3):22-31.

NARWC [North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium]. 2025. Biology - North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium Accessed on 6/5/20.

National Marine Fisheries Service. 2005. Recovery Plan for the North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalaena glacialis). National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, MD. 137 pp. file:///C:/Users/Owner/Downloads/noaa_3411_DS1 (2).pdf.

National Marine Fisheries Service. 2022. North Atlantic Right Whale (Eubalaena glacialis) 5-year Review: Summary and Evaluation. National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, MD. 55 pp. https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/s3//2022-12/Sign2_NARW20225YearReview_508-GARFO.pdf.

NEA [New England Aquarium}. 2025. Our history and what’s ahead: Right Whale research: Our History and What’s Ahead: Right Whale Research - New England Aquarium. Accessed on 6/5/2025..

North Atlantic Right Whales (Eubalaena glacialis). Office of Protected Resources, NOAA Fisheries. URL: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/north-atlantic-right-whale.

Pendleton DE, Tingley MW, Ganley LC, Friedland KD, Mayo C, Brown MW, McKenna BE, Jordaan A, and Staudinger M. 2022. Decadal-scale phenology and seasonal climate drivers of migratory baleen whales in a rapidly warming marine ecosystem. Global change biology 28(16):4989-5005.

Pershing AJ, Alexander MA, Brady DC, Brickman D, Curchitser EN, Diamond AW, McClenachan L, Mills KE, Nichols OC, Pendleton DE, Record NR, Scott JD, Staudinger MD, and Wang Y. 2021. Climate impacts on the Gulf of Maine ecosystem: a review of observed and expected changes in 2050 from rising temperatures. Elementa 9(1):00076.

Pettis HM and Hamilton PK. 2025. North Atlantic Right Whale Consortium 2024 annual report card. Report to the North Atlantic Whale Consortium. Available at: www.narwc.org.

Record NR, Runge JA, Pendleton DE, Balch Wm, Davies KTA, Pershing AJ, Johnson CL, Stamieszkin K, Ji R, Feng Z, Kraus SD, Kenney Rd, Hudak, CA, Mayo CA, Chen C, Salisbury JE, and Thompson CRS. 2019. Rapid climate-driven circulation changes threaten conservation of endangered North Atlantic right whales. Oceanography 32(2):162-169.

SNMNH [Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History].2025. Right Whale Baleen | Smithsonian Ocean Accessed on 6/5/2025.

Staudinger MD, Mills KE, Stamieszkin K, Record NR, Hudak CA, Allyn A, Diamond A, Friedland KD, Golet W, ...and Yakola K. 2019. It’s about time: a synthesis of changing phenology in the Gulf of Maine ecosystem. Fisheries Oceanography 28(5):532-566.

Staudinger MD, Goyert HG, Suca JJ, Coleman K, Welch L, Llopiz JK, Wiley D, Altman I, Applegate A, Auster P, Baumann H,...and Steinmetz H. 2020. The role of sand lances (Ammodytes sp.) in the Northwest Atlantic ecosystem: a synthesis of current knowledge with implications for conservation and management. Fish and Fisheries 21(3):522-526.

Staudinger MD, Karmalkar AV, Terwillinger K, Burgio K, Lubeck A, Higgins H, Ricer T, Morelli TL, and D’Amato A (and references therein). 2024. A regional synthesis of climate data to inform the 2025 State Wildlife Action Plans in the Northeast U.S. DOI Northeast Climate Adaptation Science Center Cooperator Report. 406 p. https://doi.org/10.21429/t352-9q86.

Contact

| Date published: | July 7, 2025 |

|---|