- Scientific name: Circus hudsonius

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Threatened (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Northern harrier in flight

The northern harrier, or marsh hawk, is a slim, long-legged, long-tailed hawk, about 40-60 cm (16-24 in) in length, with an owl-like face and long, rounded, narrow wings extending up to 1.2 m (46 in) from wing tip to wing tip. Males are pale bluish gray on the head and upper surface, white on the undersurface, and have black wing tips; the tail has a broad subterminal bar with 5 to 7 narrower dark brown bars. Females are dusky brown on the head and upper surface, and light brown with darker vertical streaks on the lower surface; the tail is dark in the center, becoming paler near the outer edges, and has 5 to 7 broad brown bars. Both sexes possess a conspicuous white rump patch, white upper tail coverts, light orange-yellow legs, and black bills. Northern harriers have large ear openings, but they are usually hidden underneath their feathers.

The male northern harrier’s gray coloration makes it distinct from other local birds. However, the female northern harrier vaguely resembles the short-eared owl (Asio flammeus): both occupy the same habitat type, have a brownish upper surface and white breast with vertical brown streaks, long rounded wings and black wingtips. However, the short-eared owl is smaller, with short, feathered legs, a white facial disk, and lacks the bright white rump patch possessed by northern harriers.

Life cycle and behavior

Northern harriers are regularly seen in Massachusetts in the winter, in habitat similar to that used for breeding. Wintering range extends from New England west to southern British Columbia and south into Central America and the West Indies. Those individuals that do migrate, begin to move south in late August or early September.

The breeding season of northern harriers extends from March to July in Massachusetts and is initiated by a spectacular courtship ritual called skydancing, which is usually performed only by males and is used to attract mates. A skydancing northern harrier performs an aerial acrobatic display of dives, somersaults, loops, and tumbles, often accompanied by shrill screaming calls.

Once the male has found a mate, the female northern harrier builds a nest made of grasses, weeds, water plants, and other vegetative material supplied to her by her mate. The nest is usually located in a slight hollowed-out area on the ground, among bushes, grasses, and other low vegetation, and consists of a thick pad of grasses surrounded by dry stalks of plants, weeds, and small twigs. Sometimes the nest is built over shallow water on a raised mound of sticks, hollowed in the center and lined with dry grass, stubble and weed stalks.

The female lays from 2-9 bluish-white eggs (3-6 on average), about 1 egg every other day. Both parents help incubate the eggs until they hatch 30-32 days later. The male harrier provides all the food to his mate and young until they fledge 30-35 days after hatching.

After the young have fledged, they may hunt together with their parents through the remainder of the summer, until they disperse on their own or are driven off. Northern harriers prey on a variety of small creatures, including rodents, rabbits, and other small mammals, small birds, insects, amphibians, reptiles, and carrion. In Massachusetts, voles constitute a very important component of the harrier’s diet; there is a direct correlation between the breeding success of northern harriers and the number of voles found in their territory. When hunting, the northern harrier flies low over the ground, slowly and systematically, usually in early morning and late afternoon or early evening. When it detects prey, it hovers a moment before swooping straight down to the ground. The harrier uses its talons to capture prey and then kills its catch via repeated stabs with its sharp beak.

Population status

Northern harriers are listed as threated under the Massachusetts Endangered Species act.

Distribution and abundance

The northern harrier breeds from Massachusetts north to Newfoundland and Alaska, south to southeastern Virginia, and west to northern Texas and central California. Wintering range extends from New England west to southern British Columbia and south into Central America and the West Indies.

Northern harriers in Massachusetts are uncommon summer residents or migrants, although they once were much more abundant in the state. Most harriers in the state that do not migrate south spend the winter in coastal marshes and the offshore islands. Some northern harriers that breed in areas north of Massachusetts may also spend the winter on the offshore islands and along the coast. Northern harriers are known to share habitat and territory with short-eared owls.

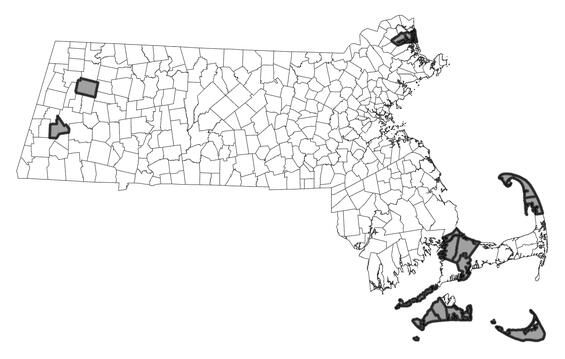

Distribution in Massachusetts. 1999-2024. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Northern harriers establish nesting and feeding territories in wet meadows, grasslands, abandoned fields, and coastal and inland marshes, mostly along the coast.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Northern harrier (Circus hudsonius)

Threats

The most significant factor in the northern harrier’s decline has been destruction of suitable habitat by reforestation of agricultural land and destruction of coastal and freshwater wetlands. In coastal areas, human disturbance may cause some harriers to abandon their nests. Natural factors such as prey abundance, prolonged periods of rain (which may destroy nests and eggs), and predation on eggs and nestlings all affect the breeding success of northern harriers. In order to prevent further decline in the northern harrier’s population, it is crucial to protect suitable habitats from development and destruction. Chicks and recent fledglings are very vulnerable to meso-predators, including dogs and cats.

Rodenticides (e.g., Second Generation Anticoagulant Rodenticides - SGARs) move up food chains and pose a threat to raptors when they consume prey that have ingested these chemicals. As a result, SGARs have been found in a high percentage of raptors that have been tested for them in Massachusetts, and it is well documented that they can kill individual raptors. However, their population-level impacts on raptors remain largely unknown.

Conservation

Maintaining suitable habitat is key to the conservation of northern harriers in Massachusetts. With most breeding occurrences now relegated to Cape Cod and the Islands, this means maintaining large tracts of diverse habitats, including grassland, maritime shrublands, cattail wetlands and scrub oak thickets. Prescribed fire and mowing are important tools for maintaining these habitats, and in turn, maintaining suitable northern harrier habitat. Northern harriers are also very sensitive to disturbance and often will abandon early nesting attempts when encroached upon by human activity, therefore trails, development and general activity should always be sited far from nest sites.

Conduct research to better understand the impacts of highly toxic rodenticides (e.g., SGARs) to raptor populations. Promote an integrated pest management approach that emphasizes the use of alternative pest control measures whenever possible to reduce negative impacts to wildlife. Coordinate with other state agencies to improve tracking and reporting of rodenticides found in wildlife and develop outreach materials for the public.

References

Clark, W.S., and B.K. Wheeler. 1987. A Field Guide to Hawks. Houghton Mifflin Co., Boston.

Johnsgard, P.A. 1990. Hawks, Eagles, & Falcons of North America. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press.

Palmer, R.S. 1962. Handbook of North American Birds. Yale University Press, New Haven & London

Serrentino, P. 1992. Northern Harrier, Circus cyaneus. Pp.89-117 in K.J. Schneider and D.M. Pence, eds. Migratory Nongame Birds of Management Concern in the Northeast. U.S. Dept. Interior, Fish & Wildlife Service, Newton Corner, MA.

Serrentino, P., and M. England. 1989. Northern Harrier, p. 37-46 in Proc. Northeast Raptor Management Symposium and Workshop. Natl. Wild. Fed., Washington, D.C.

Terres, J.K. 1991. The Audubon Society Encyclopedia of North American Birds. New York: Wing Books.

Contact

| Date published: | April 4, 2025 |

|---|