- Scientific name: Boyeria grafiana

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Species of Special Concern (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Male ocellated darner

The ocellated darner is a large, semi-aquatic insect of the order Odonata, suborder Anisoptera (the dragonflies), and family Aeshnidae (the darners). The darners are among the largest of the dragonflies, and are further characterized by exceptionally large eyes that wrap around the head and meet along a seam on the top of the head. The ocellated darner is dull brown overall with two yellow or greenish spots on the sides of the thorax (winged and legged segment behind the head) and green or greenish-yellow stripes on the top of the thorax. The abdomen is marked with small, dull green to yellow lateral markings. The sexes are similar in appearance, though the pale markings tend to be somewhat brighter and more distinct on males. Both males and females have long, ovate terminal appendages (reproductive structures). The ocellated darner is one of two species of spotted darners (Boyeria) in North America. Both are readily separated from the other groups of darners by the two pale spots on each side of the thorax.

Ocellated darners range from about 60-66 mm (2.4 to 2.6 inches) in overall length, with a wingspan averaging approximately 84 - 88 mm (3.4 inches).

The nymphs are long and slender, ranging up to 38 mm (1.5 inches) in length when fully developed. They can be identified using various characteristics, as per the keys of Soltesz (1996), and Needham et al. (2000), and Tennessen (2019).

The ocellated darner is very similar in appearance to the closely related but more common and widespread, fawn darner (B. vinosa). The two can be reliably differentiated only in the hand, using a combination of characteristics. Ocellated darners average darker and grayer overall than the paler brown fawn darner, with lateral thoracic markings tending to be more oval and frontal stripes more prominent. Abdominal markings along the lateral and dorsal sides are larger in ocellated darners. Fawn darners have small, dark patches at the base of the wings, and the wings often have a faint amber wash, both characteristics that are typically lacking in ocellated darners. These characteristics are variable and separation of these two species can be difficult if not in hand.

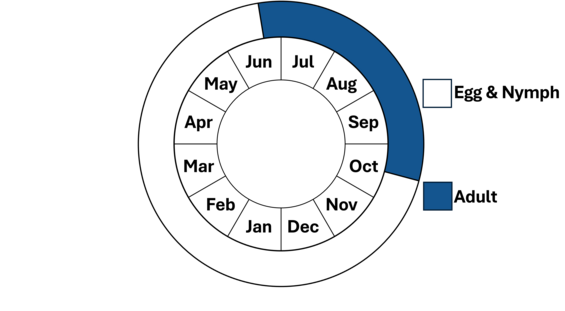

Life cycle and behavior

Note, nymphs are present year-round.

Adult males patrol up and down the shoreline, searching for females. They fly low over the water (generally within a foot of the surface), poking in and out of shoreline indentations and projections, circling around protruding rocks and vegetation. Their flight is swift and very erratic, making them difficult to capture. Unlike most odonates, ocellated darners are crepuscular and most active late in the day, often flying until well after sunset. They seem to prefer shaded rather than sunlit areas, and are often active on overcast days. Males have been observed patrolling early in the morning in Massachusetts. Unlike many darners, they are rarely seen away from water and apparently do not take part in the feeding swarms typical of most other species in the family. When not flying, the adults rest by hanging vertically from vegetation in woodlands adjacent to their breeding habitats.

Ocellated darners have a late flight season, with most records occurring from August to mid-September, and ranging from late June to mid-October.

Very little has been published on the life history of ocellated darners. However, the closely related fawn darner (B. vinosa) is better known and presumably the two species share similar life histories. The nymphs are aquatic and seem to spend most of their time clinging upside-down to the underside of rocks and submerged wood. Darner nymphs are voracious predators and typically are among the dominant predators in their aquatic habitats. Although nothing has been published on the development time of ocellated darner nymphs, the nymphs of other species in the family spend anywhere from one to four years developing.

When ready to eclose (transform from nymph to adult), the nymphs crawl out of the water onto exposed rocks, emergent vegetation, or shoreline vegetation. After pulling free from their nymphal skin (exuviae), the teneral (the period when the exoskeleton has yet to harden and the flight muscles have not fully developed) adult dragonflies fly off to nearby upland areas where they spend several days feeding and maturing. Adult darners feed on a variety of aerial insect prey, which they capture in flight with their spiny legs.

When ready to breed, the males return to their aquatic habitats and take up their shoreline patrols, looking to mate with females. Females are generally not seen at these male-dominated wetlands until the brief period when they are ready to mate and lay eggs. When a male encounters a female, he attempts to grasp her in the back of her head with claspers located on the end of his abdomen. If the female is receptive, she allows the male to grasp her, then curls the tip of her abdomen upward to connect with the male’s sexual organs located on the underside of his second abdominal segment, thus forming the familiar heart-shaped “wheel” typical of all Odonata: the male above and the female below. In this position, the pair flies off to mate, generally hidden high in nearby trees where they are less vulnerable to predators.

Like other darners, female ocellated darners have a long, thin ovipositor projecting from the underside of the end of the abdomen. They use this ovipositor to slice into emergent vegetation, mud, and decaying submerged logs where they lay their eggs. It is not known how long the eggs take to develop into nymphs.

A fresh ocellated darner exuviae clinging to boulder in a Deerfield River tributary.

Distribution and abundance

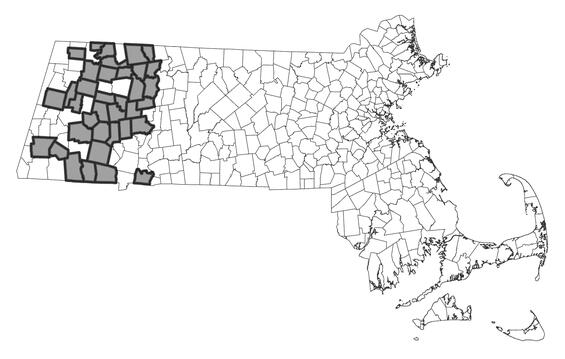

Ocellated darners range through eastern North America from Minnesota, Ontario and Nova Scotia, south to Georgia and Mississippi. The species is fairly common and widespread in Canada and northern New England, but is rather rare and local in the south, where it is confined to higher elevations, primarily in the Appalachians. In Massachusetts, ocellated darners occupy watersheds west of the Connecticut River mainstem including the Hoosic, Housatonic, Deerfield, Westfield, Farmington, and smaller watersheds that directly feed the Connecticut River. Ocellated darner exuviae and adults are typically observed in low abundance at a given site (with exceptions). However, viable populations persist in several in these watersheds (e.g., Deerfield) based on widely distributed observations in multiple streams and rivers.

Ocellated darners are listed as a species of special concern in Massachusetts. As with all species listed in Massachusetts, individuals of the species are protected from take (picking, collecting, killing, sale, etc.) and sale under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Ocellated darners nymphs inhabit clear, rocky, swift-flowing streams and rivers and large, rocky, poorly vegetated lakes. Adults also inhabit nearby uplands, often forests with mixed coniferous and deciduous trees. In Massachusetts, ocellated darners primarily occupy moderate to high gradient, cool to cold, rocky streams and rivers.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Typical small to mid-sized stream habitat suitable for ocellated darner. Images by Charlie Eiseman & Julia Blyth.

Threats

Degradation of water quality and alteration of streamflows are major threats to ocellated darner. Although the known Massachusetts sites seem to be well-protected, many of these rivers are paralleled by roadways for much of their length, and salt and other road contaminant run-off is of concern. Other run-off including industrial and chemical pollution is also a threat. Warming stream temperatures from climate change is projected to reduce ocellated darner habitat in Massachusetts (Collins and McIntyre 2017). Altered streamflows from hydroelectric peaking operations may cause mortality during eclosion and teneral stages. Additional threats include deforestation of upland habitats adjacent to nymphal streams, illegal or accidental industrial discharge, and hardening of channel banks and siltation that creates unstable stream habitat.

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

Recent efforts have expanded our knowledge of ocellated darner distribution and abundance largely through exuvia surveys. Since adults are difficult to detect because of their erratic flight behavior and crepuscular activity, exuvia not only provides increased detection but also site-specific locations of aquatic nymph and breeding habitat.Surveys may target adults in combination with exuviae but never alone. Robust stream populations should be routinely monitored every five years or to the extent practical to document changes in occupancy and habitat conditions. Effort should also target under-surveyed streams and stream segments identified as potentially suitable habitat.

Management

Upland and stream protection is critical for the conservation of ocellated darner. Water quality is of primary concern. Protection of forested upland borders of these river systems are critical in maintaining suitable water quality and are critical for feeding, resting, and maturation. Development of these areas should be discouraged, and the preservation of remaining undeveloped uplands should be a priority. Alternatives to commonly applied road salts should tested to minimize freshwater salinization. Altered streamflows from hydroelectric operations should minimize rapid flow increase during emergence time to prevent mortalities. Hardened and channelized stream segments should be restored to promote natural sediment dynamics.

Research needs

Research effort is needed to update species distribution models coupled with climate change projections to identify vulnerable and climate resistant streams for ocellated darner. Further research is also needed to identify habitat requirements, source and sink populations, and colonization rates.

References

Collins S.D., and N.E. McIntyre. “Extreme loss of diversity of riverine dragonflies in the northeastern U.S. is predicted in the face of climate change.” Bulletin of American Odonatology 12,1 (2017):7-19.

Dunkle, Sidney W. Dragonflies Through Binoculars. Oxford University Press, 2000.

Lam, E. Dragonflies of North America. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2024.

Needham, J.G., M.J. Westfall, Jr., and M.L. May. Dragonflies of North America. Scientific Publishers, 2000.

Nikula, B., J.L. Ryan, and M.R. Burne. A Field Guide to the Dragonflies and Damselflies of Massachusetts. 2nd ed. Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, 2007.

Paulson, D. Dragonflies and Damselflies of the East. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Soltesz, K. Identification Keys to Northeastern Anisoptera Larvae. Center for Conservation and Biodiversity, University of Connecticut, 1996.

Tennessen, K. Dragonfly Nymphs of North America: An identification guide. Springer, 2019.

Walker, E.M. 1958. The Odonata of Canada and Alaska, Vol. II. University of Toronto Press.

Contact

| Date published: | March 6, 2025 |

|---|