Introduction

In 2017, the city of Methuen (“City”) negotiated new contracts with both of its police unions: the Methuen Police Patrolmen’s Association (the “patrol officers’ union”), which represents the sworn patrol officers; and the Methuen Police Superior Officer’s Association, New England Police Benevolent Association, Local 17 (the “superiors’ union”), which represents the sworn superior officers with the rank of sergeant, lieutenant or captain. On September 18, 2017, the Methuen City Council voted to approve new contracts for both unions.

The resulting contract with the superiors’ union (“Superiors’ Contract”) determined the salary and benefits for each Methuen superior officer for the period of July 1, 2017 to June 30, 2020.3 During the relevant time period, there were 26 superior officers in the Methuen police department. The Superiors’ Contract contains several changes from the prior contract.

During contract negotiations with the superiors’ union, Mayor Stephen Zanni wanted the union to agree to a cost-of-living adjustment that would result in raises of 0% in the first year of the contract, 2% in the second year and 2% in the third year. In gaining the superiors’ union’s agreement to this cost-of- living adjustment, Mayor Zanni agreed to other, more substantial, pay increases without ever determining their financial impact on the City. Most significantly, Mayor Zanni agreed to certain changes to the contractual definition of “base pay”; this dramatically increased the superior officers’ salaries.

Specifically, the negotiations yielded changes to the follow aspects of superior officers’ total compensation:

- Base pay

- Holiday compensation

- Uniform allowances

- Protective vest stipend

- Cost-of-living adjustment

- Rank-differential pay

- Specialty-position pay4

Moreover, on two occasions after the negotiations were complete – and without Mayor Zanni’s consent – the union president added language to the contract that further increased the superior officers’ total compensation.

On September 18, 2017, Mayor Zanni presented the Superiors’ Contract to the Methuen City Council. Mayor Zanni told the City Councilors – inaccurately – that the City had only agreed to a cost-of-living adjustment. The City Council unanimously approved the Superiors’ Contract that same night, with less than one minute of discussion.5

I. Overview of the Negotiations

The City and the Methuen superiors’ union met on six occasions during the spring and summer of 2017 to negotiate a new contract.6 Captain Gregory Gallant was (and still is) the president of the superiors’ union and represented it in the negotiations. Lieutenant Joseph Aiello was (and still is) the union’s vice president and represented it during negotiations. Attorney Gary Nolan is the union’s attorney, but he was not present for the contract negotiations.

During the negotiations, four individuals represented the City as its designated representatives: Mayor Stephen Zanni, the chief executive of the City; Richard D’Agostino, the city solicitor; Ann Randazzo, the assistant city solicitor and human resources director; and Joseph Solomon, Methuen’s police chief.7 All four individuals are experienced in negotiating collective bargaining agreements. Chief Solomon’s role was to provide police expertise to the City regarding various requests from the parties.

In 2017, Mayor Zanni entered negotiations with all City unions with the intent that all union members would receive a cost-of-living adjustment of 0% in fiscal year 2018, 2% in fiscal year 2019 and 2% in fiscal year 2020. During negotiations with the superiors’ union, therefore, Mayor Zanni focused heavily on garnering an agreement for the cost-of-living adjustment. The superiors’ union entered into negotiations requesting a cost-of-living adjustment of 2% in fiscal year 2018, 3% in fiscal year 2019 and 3% in fiscal year 2020.

As discussed in Finding VIII, however, the costliest request by the superiors’ union was changing the contractual definition of base pay to include additional types of compensation.

Various drafts of the Superiors’ Contract reflect some of the superiors’ union’s requested changes to base pay. At certain times in the negotiations the City’s representatives asked how much it would cost to make the requested changes to base pay. Mayor Zanni ultimately agreed to the superiors’ union requests without determining their financial impact. The notes created during the negotiation sessions demonstrate that the parties openly discussed certain changes to the definition of base pay and that Mayor Zanni agreed to them.

Captain Gallant told the OIG that at the conclusion of the negotiations, he estimated that captains’ total compensation (before overtime and details) would be approximately $200,000 to $250,000 per year. As explained more fully in Finding VIII below, however, Captain Gallant later added a special formula to the contract and changed the definition of base pay to include officers’ educational incentive.

These changes created a more significant impact, which ultimately led to increasing the superiors’ salaries by between 35% and 183%.

II. Mayor Zanni Agreed to Costly Salary Increases.

During negotiations, the union ultimately agreed to Mayor Zanni’s proposed cost-of-living adjustments. Mayor Zanni, however, agreed to several other changes that significantly increased the superior officers’ total compensation.

A. Mayor Zanni Agreed to Change the Definition of Base Pay to Include Additional Types of Compensation.

Under their respective contracts, Methuen police officers’ total compensation is comprised of several different elements, including base pay, cost-of-living adjustments, stipends, incentives and allowances. Stipends, incentives and allowances include items such as holiday compensation, shift differentials, uniform allowances, rank differentials, longevity pay, protective vest stipend and educational incentives (see Appendix 2, Glossary of Frequently Used Contract Terms).

Base pay is the foundation from which all other percentage-based compensation, such as longevity and shift-differential pay, is calculated. Therefore, an increase to base pay results in an increase to certain other stipends, incentives and allowances. For example, if a superior officer with a base pay of $100,000 works a midnight shift, that officer would receive an additional $11,000 per year in shift differential pay. If that officer’s base pay increased to $200,000, the same shift differential would increase to $22,000 per year.

In addition, the base pay for subordinate officers is used to calculate the base pay of higher ranked officers. For instance, if lieutenants had a 116% rank differential, then each lieutenant’s base pay would be 116% of the highest-paid sergeant’s base pay. Therefore, if the highest-paid sergeant earned $80,000 per year in base pay, a lieutenant’s base pay would be $92,800 (i.e., $80,000 x 116%).

Under the superior officers’ previous contract (the “2014 Contract”), base pay meant just that: an officer’s base salary before adding in stipends, allowances and incentives. During negotiations of the Superiors’ Contract, however, Mayor Zanni agreed to change the definition of base pay to also include holiday compensation, the uniform allowances and the protective vest stipend (this change to base pay is referred to as “artificial base pay”).8

This change increased superior officers’ pay in two different ways. First, it meant that superior officers’ base pay would be calculated using subordinate officers’ artificial base pay:

Base pay

Holiday compensation

Uniform allowances

+ Protective vest stipend

_________________

= Artificial Base Pay

For instance, if a lieutenant’s rank differential was 116%, their base pay would be 116% of the highest-paid sergeant’s artificial base pay. Put another way, the lieutenant would receive an additional $1.16 in base pay for each dollar that the highest-paid sergeant earned in holiday compensation, uniform allowances and protective vest stipends.

Second, the change also meant that an officer’s percentage-based compensation, such as longevity and shift-differential pay, were to be calculated using that officer’s artificial base pay. As previously discussed, under the 2014 Contract when officers worked the night shift, they were paid 111% of their base pay. When he negotiated the Superiors’ Contract, Mayor Zanni agreed to pay officers 111% of their artificial base pay for working at night.

B. Mayor Zanni Agreed to Other Changes that also Increased the Superior Officers’ Total Compensation.

Mayor Zanni agreed to additional changes that also increased the superior officers’ total compensation.

a. Holiday compensation (Article XII): During negotiations, the superiors’ union requested two changes to holiday compensation, which is calculated as one-and-a-half times an officer’s base pay for working any of 13 specific holidays. First, the union asked to include the educational incentive in the definition of base pay for the purposes of calculating holiday compensation.9 Under the new contract, this meant that when an officer worked on a holiday, his hourly rate would be calculated using his artificial base pay plus his educational incentive:

(Artificial Base Pay + Educational Incentive) x 1.5

Second, the union requested that the City include that final holiday compensation as part of the officers’ base pay for the purpose of calculating certain other pay.

According to the notes from the negotiations, the City’s representatives raised questions about the potential cost of including holiday compensation in the definition of base pay. Mayor Zanni declined to seek answers to any of those questions. On August 7, 2017, without requesting further information from the union or the city auditor regarding cost, Mayor Zanni agreed to both changes.10 Mayor Zanni then directed Chief Solomon to draft the new language for holiday compensation.

This is the only time Mayor Zanni agreed to include the educational incentive in the definition of base pay.

b. Uniform allowances (Article XVII): The City pays the superior officers two allowances related to their uniforms. The first allowance provides money to replace their uniforms (“uniform allowance”) and the second provides money to clean their uniforms (“cleaning allowance”).

In the 2014 Contract, each uniform allowance was $900 a year ($1,800 total) and the City paid the allowances in a lump sum once a year. During negotiations, the superiors’ union asked to increase each allowance to $1,200 per year. Mayor Zanni agreed.11 As discussed above, moreover, Mayor Zanni also agreed to add the uniform allowances to the definition of base pay.

c. Protective vest stipend (Article XXIX, Section 25): The superiors’ union requested that the City pay the superior officers for a variety of “extra requirements,” including requiring them to wear a bulletproof vest and being trained to carry and administer Narcan. Mayor Zanni agreed to pay each superior officer $500 in fiscal year 2019 and $1,000 in fiscal year 2020 for this stipend, which earlier contracts referred to as the hazardous duty stipend. As discussed above, moreover, Mayor Zanni also agreed to add the protective vest stipend to the definition of base pay.

d. Specialty position pay (Article XXIII): The superiors’ union requested that superior officers assigned to certain divisions of the police department, such as the detectives’ unit and the school resource division, receive the base salary of the next highest rank. For example, the union asked that the lieutenant supervising the school resource division be paid at a captain’s rank. This provision was not in the 2014 Contract. Mayor Zanni agreed to the request.

III. The President of the Superiors’ Union Drafted the Superiors’ Contract.

After the negotiations between the superiors’ union and the City concluded, the city solicitor asked the representatives of the superiors’ union to draft the new contract. He made the request because he thought it would protect the City should the superior officers later dispute the meaning of a contract term. The City Solicitor believed that if the superiors’ union drafted the language, it prevented the union from later suggesting that the language did not accurately reflect the negotiations.

With the exception of one clause, the union president, Captain Gallant, drafted the new language for the Superiors’ Contract. Negotiation notes indicate that, at Mayor Zanni’s request, Chief Solomon drafted the language regarding holiday compensation (Article XII). The City Solicitor never asked to review any draft language to ensure that it accurately contained the agreements bargained for in the negotiations.

Captain Gallant elected not to include a salary schedule in the Superiors’ Contract. A salary schedule is a table that shows the salary range each rank of officer can receive.

Typically, the top rows list the different ranks with variations of experience. The descending columns show the salary levels. Captain Gallant was familiar with salary schedules but chose to omit one from the contract. Had he included a salary schedule, it would have outlined the specific base salary each superior officer would receive under the Superiors’ Contract. A salary schedule is part of all of the surrounding communities’ union contracts for their superior officers.

IV. Captain Gallant Included a Non-Negotiated Term in the First Draft of the Superiors’ Contract.

When Captain Gallant drafted the Superiors’ Contract, he did not follow the parties’ agreement with respect to the protective vest stipend (Article XXIX Miscellaneous, Section 25).12 As previously discussed, Mayor Zanni agreed to pay each superior officer $500 in fiscal year 2019 and $1,000 in fiscal year 2020 for this stipend. However, Captain Gallant drafted language providing that each superior officer would receive 1% of their base pay during fiscal year 2019 and 2% during fiscal year 2020.13

The change substantially increased the stipend for some superior officers. Under Captain Gallant’s drafting, a superior officer only had to make $50,000 to receive $500. No superior officer’s base pay was less than $80,125. With the additional changes Captain Gallant made, some superior officers stood to receive up to $2,000 in fiscal year 2019 and $4,000 in fiscal year 2020.

V. The City Did Not Do a Cost Analysis Before Agreeing to the New Contract.

During the negotiations, the City’s representatives never asked the City Auditor to analyze the financial impact of any of the superiors’ union’s requested changes, such as the change to the definition of base pay. The only cost calculation Mayor Zanni did ask of the City Auditor was for the agreed-upon cost-of-living adjustment. Crucially, however, Mayor Zanni failed to inform the City Auditor that he had agreed to change the definition of base pay.

Without that information, the City Auditor could not accurately calculate the impact of the cost-of-living adjustment because it is a percentage of base pay. That is, when base pay increases, the amount the officers receive from a cost-of-living adjustment also increases.

VI. The President of the Superiors’ Union Made Changes to the Contract After Union Ratification.

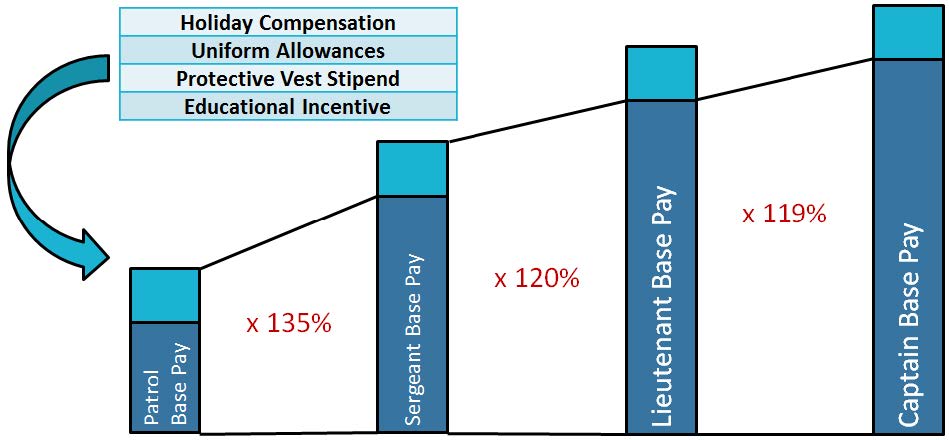

On August 30, 2017, Captain Gallant presented the draft contract to the superiors’ union for ratification. The superiors’ union immediately voted to ratify the contract. On August 31, 2017, Captain Gallant signed the Superiors’ Contract and delivered it to Mayor Zanni for his signature. The contract the superiors’ union ratified and the contract Captain Gallant delivered to Mayor Zanni were identical. The contract did not have any language regarding the cost-of-living increase.

Chief Solomon returned the contract to Captain Gallant without Mayor Zanni’s signature. Chief Solomon informed Captain Gallant that Mayor Zanni wanted the compensation clause in the contract (Article XXIV) to include the cost-of-living adjustment that the parties had agreed to (i.e., language stating that the superior officers would receive a 0%, 2%, 2% cost-of-living adjustment over the next three years). Captain Gallant inserted language reflecting the cost-of-living adjustment.

Captain Gallant then made additional changes that the City had not negotiated, requested or agreed to. First, he revised the provisions on holiday compensation (Article XII), uniform allowances (XVII, Section 2) and the protective vest stipend (Article XXIX, Section 25) to include language to further emphasize that those items should be included in the contract’s definition of base pay. Second, he changed the compensation provision (Article XXIV) to:

a) Add the educational incentive to the definition of base pay

b) Spell out in detail how the City was required to calculate base pay

Specifically, Captain Gallant inserted a formula for calculating base pay (the “Gallant Formula”), after first determining which formula would be most advantageous to the superior officers. The Gallant Formula was substantially different from those used in prior agreements and it had the effect of dramatically increasing the superior officers’ total compensation. Specifically, Captain Gallant inserted the following language to the compensation provision (Article XXIV):

Base pay and added base pay calculations are to be calculated in the

following order and manner to arrive at base for all purposes; Base pay,

then add cleaning allowance, subtotal, then calculate and add Holiday

compensation under Article XII, then add calculated Protective Vest/Hazardous Duty and Technology Compensation percentage [i.e., protective vest stipend], calculate Quinn Bill/Education Incentive [i.e., the educational incentive].14

The chart below illustrates the difference in the definitions of base pay between the 2014 Contract, the changes Mayor Zanni agreed to during negotiations, and the final Superiors’ Contract. Finding VIII details how changing the definition and adding the Gallant Formula created a drastic difference in the superior officers’ base pay.

| 2014 Contract | Changes to the Definition of Base Pay that Mayor Zanni Agreed To | 2017 Superiors’ Contract With Captain Gallant’s Revised Definition to Base Pay |

|---|---|---|

| Holiday Compensation | Holiday Compensation | |

| Uniform Allowances | Uniform Allowances | |

| Protective Vest Stipend | Protective Vest Stipend | |

| Educational Incentive | ||

| Base Pay | Base Pay | Base Pay |

| =Base Pay | ="Artificial Base Pay" | ="Inflated Base Pay" |

It is noteworthy that Captain Gallant also reformatted the compensation provision (Article XXIV) in a way that made the new language less obvious.

In the version he originally provided to the members of the superiors’ union and Mayor Zanni, Article XXIV was double spaced, like the rest of the contract. When he inserted the Gallant Formula, Captain Gallant reformatted that page of the contract – and only that page of the document – in order to fit it onto the same page. Specifically, he changed the spacing of the first page of Article XXIV to single-spaced so no new language continued onto the next page. Therefore, by reformatting that one page, the rest of the pages in the contract appeared the same as they had in the version Captain Gallant sent to Mayor Zanni and the union members.

Captain Gallant also added page numbers to the revised Superiors’ Contract, except on the signature page. The version Captain Gallant originally sent to Mayor Zanni – i.e., the version the union ratified – did not contain page numbers. Captain Gallant did not update the date on the signature page.15

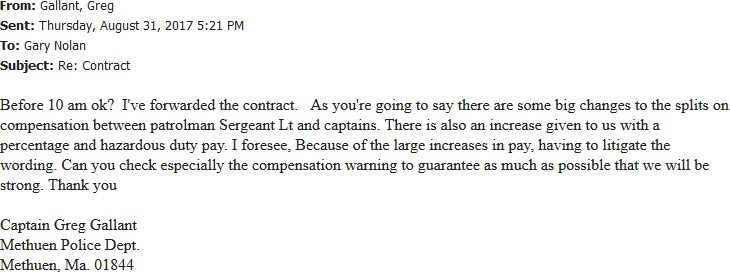

On August 31, 2017, Captain Gallant emailed Gary Nolan, the superiors’ union attorney, via his city email account:

After Attorney Nolan suggested a time to discuss the contract, Captain Gallant replied that there were “great increases, and it all compounds":

Attorney Nolan responded that he hoped the City “doesn’t bring their calculators.”16 Captain Gallant never sent his new formula to the union members to review or ratify.

VII. The City Did Not Review the Final Contract Before Approving It.

On September 6, 2017, Captain Gallant personally returned the revised version of the Superiors’ Contract to Mayor Zanni. Captain Gallant told the OIG that he tabbed the page with the compensation clause (Article XXIV). The City’s copy does not have any tabs on it. Further, he only informed Mayor Zanni that he had added the cost-of-living adjustment to Article XXIV. According to both Mayor Zanni and Captain Gallant, Captain Gallant did not tell him that he made any other changes to the contract, such as inserting the Gallant Formula for calculating base pay.

Mayor Zanni signed the contract the day he received it.17 He did not review the entire contract before signing it. He did not review the city solicitor’s notes prior to signing the Superiors’ Contract to ensure it accurately embodied the agreements made over the six negotiation sessions. He failed to keep any notes or records regarding any agreements or communications he had about the Superiors’ Contract.

In addition, Mayor Zanni never asked the city solicitor to review the Superiors’ Contract in advance of signing it, and neither of the City’s attorneys reviewed it before Mayor Zanni signed it. Nor did Mayor Zanni ask the city auditor to review the contract before signing it.

Mayor Zanni did not have any witness present when he signed the contract. The parties did not initial each page of the contract. Mayor Zanni kept the version of the Superiors’ Contract that had the original signatures. The superiors’ union kept a copy of the signed contract.

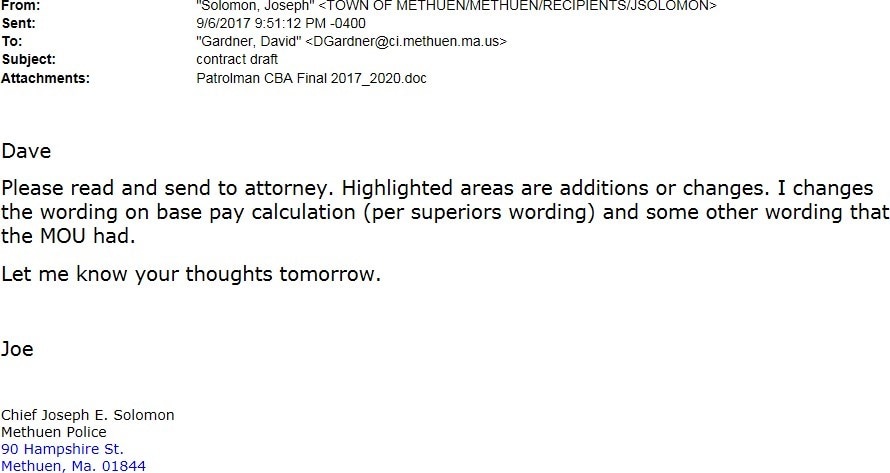

On September 6, 2017, almost immediately after signing the Superiors’ Contract, Captain Gallant emailed it to Chief Solomon. Chief Solomon and Mayor Zanni’s office each submitted the Superiors’ Contract to the City Council’s clerk for presentation at the September 18, 2017 City Council meeting.

The city solicitor received the Superiors’ Contract from the City Council’s clerk in advance of the September 18, 2017 City Council meeting, but he did not review it. The city solicitor never informed the City Council that they had never reviewed the Superiors’ Contract.

When Mayor Zanni presented the contract to the City Council for approval, he told the city councilors the Superiors’ Contract only increased the superior officers’ salaries via the cost-of-living adjustment.

As discussed throughout this report, that was untrue. On September 18, 2017, no members of the City Council asked any questions about the Superiors’ Contract.18 Nor did any councilor ask the city auditor for his opinion of the financial impact or budgetary constraints the contract would create.19 The City Council approved the Superiors’ Contract in two votes less than an hour apart.20

VIII. The Superiors’ Contract Resulted in Raises of Approximately 35% to 183%.

As previously discussed, in the 2014 Contract, a superior officer’s base pay was calculated using only the base pay of subordinate officers. The Superiors’ Contract created an “inflated base pay” for each superior officer. For example, a sergeant’s base pay was to be calculated using the inflated base pay of the highest-paid patrol officer.21

Additionally, the Gallant Formula had a compounding effect that benefited officers of a higher rank. For instance, a lieutenant’s base salary was to be calculated using the highest-paid sergeant’s inflated base pay, which in turn was calculated using the highest-paid patrol officer’s inflated base pay.22

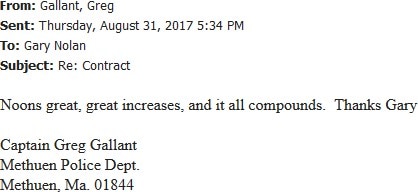

Figure 1. Illustration of the Gallant Formula’s impact on superior officers’ base salaries.

Based on documents provided by the City, for instance, the captains’ base pay went from $107,505 under the prior contract to $287,719 in 2017.23 To further illustrate the compounding effect of the Gallant Formula, the City estimated that some captains would receive as much as $77,457 annually in educational incentives for degrees they earned and for degrees earned by subordinates. This is approximately $50,000 more per year than under the prior contract. Appendix 4 further highlights how changing the definition of base pay and adding the Gallant Formula created a drastic difference in the way that the superior officers’ pay was to be calculated.

Estimates of salaries under the Superiors’ Contract varied due to the complexity of the agreement’s compensation formula, but all indicated that the superior officers would receive exceptionally large pay increases.24

It was estimated that the salaries of captains, lieutenants and sergeants would rise to an average of $432,000, $269,000 and $160,000, respectively, not including overtime or paid details.

All told, different calculations estimated that the Superiors’ Contract called for raises of approximately 35% to 183% over the previous year.25 See Appendix 7 for a comparison of the superior officers’ salaries with the salaries of superior officers in certain similarly situated communities.

IX. Discovery of the Effect of the Superiors’ Contract.

Mayor James Jajuga took office in January 2018. The city solicitor, assistant city solicitor and the city auditor remained in their respective positions.26 Mayor Jajuga immediately learned from the city auditor that the Superiors’ Contract exponentially increased the pay of the superior officers far beyond the cost-of-living increases that Mayor Zanni reported to the Methuen City Council prior to its vote on September 18, 2017.27

After meeting with Mayor Jajuga, the city auditor and his staff began calculating the cost of the contract as it related to each individual superior officer. Because the Superiors’ Contract redefined base pay, the City had to calculate each individual superior officer’s pay; it was an intricate and time-consuming process. By contrast, in previous contracts the stipends were easy to calculate as the base pay for each superior officer was a static number. After completing the calculations, the auditor provided his estimates to Mayor Jajuga.

The police department budget could not sustain the new salaries without additional funding or significant layoffs.

Consequently, Mayor Jajuga immediately attempted to privately renegotiate the Superiors’ Contract with the superiors’ union, including Captain Gallant. Captain Gallant told the OIG that he did not understand the compounding effect of his formula until Mayor Jajuga reached out to renegotiate. Captain Gallant claimed he did not intend for his formula to have a compounding effect. Captain Gallant told the OIG that he only intended to have the superior officers’ educational incentive calculated for each superior officer; that is, subordinate officers’ educational incentives were not supposed to be used to calculate superior officers’ base pay.

His email from August 31, 2017 – in which he stated that “it all compounds” – suggests otherwise (see Finding VI). Regardless of his original intent, Captain Gallant failed to tell Mayor Jajuga that he added the clause without negotiating it with the City.

Mayor Jajuga’s private negotiations failed. Consequently, on April 17, 2018, Mayor Jajuga first publicly warned the City Council about the exponential salary increases for Methuen superior officers. Upon the public disclosure, Mayor Zanni called Captain Gallant and told him that the City had not agreed to such dramatic raises. Captain Gallant informed Mayor Zanni that the reported salary numbers were inaccurate. This statement was not true.

In contrast to the former mayor, other city leaders took no action in response to Mayor Jajuga’s announcement. First, the city solicitor did not review the Superiors’ Contract. He did not compare it against his notes from the negotiations to determine how the contract caused such exponential increases. Had he done this in April 2018, it would have been immediately apparently that the contract contained several provisions, including the Gallant Formula, that the City had not negotiated. The city solicitor did not realize until February 2019 that the contract contained the formula Captain Gallant created after the negotiations.

Similarly, despite the extensive negative publicity and concern regarding the police budget, Chief Solomon never publicly acknowledged that the Superiors’ Contract contained provisions, including the Gallant Formula, that the City had not agreed to. During its investigation, moreover, the OIG found no evidence that Chief Solomon privately informed anyone that the City’s negotiating team had not agreed to several provisions in the contract, including the Gallant Formula.

X. Memorandum-of-Understanding Negotiations.

In the summer of 2018, due to issues with the Methuen schools’ budget and public outcry regarding the Superiors’ Contract, the City and the superiors’ union negotiated a memorandum of understanding (“MOU”) regarding the superior officers’ pay. The City’s negotiating team for the MOU included the city solicitor and Chief Solomon. At the time of the MOU discussions, the city solicitor still had not compared his negotiation notes with the Superiors’ Contract. In fact, he still had not read the Superiors’ Contract.

During the MOU discussions, the city auditor created a spreadsheet detailing the step-by-step calculations for each superior officer’s total compensation following the Gallant formula. Chief Solomon participated in these discussions. Chief Solomon also calculated the superior officers’ salaries, using a different methodology, and provided those calculations to the city auditor (see Appendix 4). The superiors’ union provided no independent calculations of their own. Chief Solomon still did not inform anyone that the Gallant Formula was not part of the original contract negotiations.

The MOU that Mayor Jajuga proposed called for raises of approximately 12% to 25% for superior officers. This was less than the raises called for under the Superiors’ Contract, but substantially more than the cost-of-living adjustments that Mayor Zanni informed the City Council he had agreed to during the contract negotiations. At no time during the MOU discussions did Captain Gallant or Chief Solomon inform the City that the former administration had never agreed to the Gallant Formula. Instead, both advocated for larger salary increases than the parties had agreed to in the summer of 2017. Additionally, Captain Gallant remained silent about the other non-negotiated changes he had made to the contract (see Findings IV and VIII above).

Mayor Jajuga and the superiors’ union agreed to the MOU on July 18, 2018. The police department’s budget could not support the raises called for in the MOU, however. Between July 2018 and January 2019 Mayor Jajuga informed City Council that the Police Department needed an additional $1.8 million in order to fund the MOU. The City Council refused to increase the department’s budget to fund the cost of the MOU. As a result, the City began the process of laying off 50 patrol officers.

Notwithstanding the threatened layoff of over half of the Methuen Police Department, Chief Solomon and Captain Gallant remained silent.

After the OIG released its February 2019 Letter, which called into question whether the MOU was enforceable, Mayor Jajuga notified the superiors’ union that he would not honor the MOU and instead would revert to paying the superiors’ under the 2014 contract.28 In response, the superiors’ union filed a “class action grievance” against the City.29 The City’s independent auditor estimates that the cost of the superiors’ union’s action for back wages could “well exceed” $2,000,000.30 The City and superiors’ union are currently litigating the grievance with an arbitrator.

XI. Chief Solomon’s Contract.

During its investigation, the OIG also examined Chief Solomon’s current contract with the City. As discussed below, the OIG found that even though his salary is tied to the patrol officers’ pay, Chief Solomon was one of the City’s representatives when it negotiated a new contract with the patrol officer’s union. While the negotiations were occurring, he privately told the patrol officer’s union to include contract language that significantly increased his salary.

The OIG further found that Chief Solomon’s contract contains undefined terms that fiscally damaged the City and substantially increase his total compensation.

A. The Police Chief Represented the City in Contract Negotiations Even Though His Pay and Benefits are Based on the Pay and Benefits of the Officers Under his Command.

In February 2017, Chief Solomon negotiated an extension to his contract with Mayor Zanni. The parties executed the agreement on February 21, 2017, and the City Council subsequently approved it without discussion or debate.31

Under the contract, Chief Solomon’s pay and benefits are based on the pay and benefits of the officers under his command. First, Chief Solomon’s contract requires the City to pay him a salary that is 2.6 times the highest-paid full-time patrol officer.32 The contract also requires the City to pay him every element of compensation and give every leave benefit that any other officer under his command receives (see Section B below).

Nevertheless, as discussed above, in the summer of 2017 Chief Solomon represented the City in contract negotiations with both the superior officers’ and the patrol officers’ unions.

When Captain Gallant sent Mayor Zanni the updated version of the Superiors’ Contract with the Gallant Formula, he also emailed the contract to Chief Solomon. Within two and a half hours after receiving the updated contract, Chief Solomon told the president of the patrol officers’ union to add the Gallant Formula to the patrol officers’ contract.33 Specifically, on September 6, 2017, Chief Solomon wrote:

He did this even though he represented the City in the contract negotiations and even though this change would substantially increase the City’s costs under the patrol officers’ contract.34 As a result, the patrol officers’ new contract included identical language to the Superiors’ Contract that also created an inflated base pay.35 It stated:

Effective July 1, 2018 base pay and added base pay are to be calculated in the following order and manner to arrive at base pay for all purposes; Base pay, then add cleaning allowance, subtotal, then add Technology Compensation, then calculate Quinn Bill/Education Incentive.

Effective July 1, 2018 base pay and added base pay calculations for any officer hired after July 1, 2013 are to be calculated in the following order and manner to arrive at base pay for all purposes; Base pay, then add cleaning allowance, subtotal, then add Technology Compensation, then calculate Educational Incentive payments for his/her degree per Article XXIV Section 15(c).36

No one gained more from the addition of the inflated base pay language than Chief Solomon.

According to his contract, he is to receive $2.60 for every $1.00 the City pays the highest-paid patrol officer. Adding the Gallant Formula to the patrol officers’ base pay meant the City would pay Chief Solomon $2.60 for each $1.00 it paid the highest-paid patrol officer for uniform allowances, holiday compensation, protective vest stipends and educational incentives. To illustrate this, the highest-paid patrol officer received $7,742.23 in educational incentive in 2017. By adding the Gallant Formula to the patrol officers’ contract, Chief Solomon got a $20,129.80 raise for his subordinate’s education. This is in addition to receiving an educational incentive for his own degrees.

The combination of the patrol officers’ and superior officers’ contracts placed Chief Solomon’s annual pay at $375,548. Mayor Jajuga refused to allocate those funds to Chief Solomon’s salary. Instead, the City paid Chief Solomon $298,410 for fiscal year 2020.37 City records demonstrate that Chief Solomon’s salary has nearly doubled from $153,456 in fiscal year 2017 to at least $297,271 in fiscal year 2021.

B. The Police Chief’s Contract Contains Undefined Terms and Lacks Provisions on Accountability.

The OIG also found that the Chief Solomon’s contract contains undefined terms that substantially increase his salary without oversight from the City. First, Chief Solomon’s contract provides that he receive every benefit that any patrol officer or any superior officer receives. In particular, the contract contains the following clause:

The Chief shall receive the maximum of the following benefits: at least the same amount of sick days, vacation days, personal days, bereavement days, holiday compensation, longevity pay, educational incentive/Quinn, uniform and cleaning allowance, health and life insurance, contractual time, training/seminar compensation time, hazard duty pay, and other benefits as do any of the regular police officers of any rank of the City receive as of the execution date of this contract.38

As set forth in the quoted language, the clause even includes an undefined catchall of “other benefits.”

In addition, despite requiring the chief of police to be available 24 hours a day, seven days a week, Mayor Zanni also agreed to permit Chief Solomon to earn “compensatory time” when he works outside of “regular business hours.”39 There is no definition of what “regular business hours” entail for the chief of police. Further, the contract does not spell out the process for tracking Chief Solomon’s time or for approving requests to earn compensatory time.

The contract also requires the City to budget and pay for Chief Solomon to attend unlimited trainings – including short courses, institutes, seminars and conferences – that Chief Solomon deems reasonably necessary for his professional development. The contract does not explicitly require Chief Solomon to obtain prior approval from the City for training, nor does his contract limit the type or amount of training expenses that he will be reimbursed for. Further, the contract does not require that the funds come from the police department budget. Instead, the contract expressly states that the City must pay for Chief Solomon’s trainings and related reimbursements out of its budget.40

Further, the contract contains an extensive discipline process favoring Chief Solomon should the City attempt to discipline him. If Chief Solomon involuntarily resigns as a result of a formal suggestion by the City that he do so, the City must pay Chief Solomon the balance of his five-year contract, regardless of the cause for the resignation.41

XII. The OIG’s 2019 Letter to the City and the State Ethics Commission’s Findings

On February 1, 2019, the OIG published a letter concerning the process the City followed in approving the Superiors’ Contract. That letter focused on the former mayor’s and City Council’s violations of duties, rules and laws related to public contracting.

Specifically, the OIG found that:

- The Council appeared to have improperly invoked the Rule of Necessity by, among other things, failing to publicly identify the conflicted councilors and the nature of their conflicts.

- The former mayor and the Council violated City Resolution #4720, which requires a financial impact statement and a memorandum explaining the differences between the current and proposed contracts prior to approval.

- The Council violated the City Charter and a City Ordinance by voting to approve the Superiors’ Contract twice on the same day.

- Then-Mayor Jajuga violated Section 4 of Chapter 40 of the General Laws and the City Charter by paying the superior officers under a MOU that the City Council never approved.

- The former mayor and former and current city councilors violated the duties of care and due diligence that they owe as elected officials to the residents of Methuen by negotiating and approving the Superiors’ Contract either without understanding the financial impact of the contract, or by understanding the financial impact and approving it anyway.42

The OIG further found that if the City were to pay under the Superiors’ Contract, it would constitute a waste of public funds and that it was unlikely that the Superiors’ Contract and MOU were legally enforceable agreements.43 The OIG recommended that the City Council consult with the State Ethics Commission regarding potential violations of the state’s conflict-of-interest laws.44

After the OIG released its 2019 letter, on April 30, 2020, the State Ethics Commission issued public education letters to three former city councilors: James Jajuga, Lynn Vidler and Jamie Atkinson.45 The State Ethics Commission found that the three councilors relied on erroneous legal advice from the city solicitor regarding the rule of necessity and that they voted on the Superiors’ Contract in violation of the state’s conflict-of-interest laws.46

Contact for OIG Report 2020: Leadership Failures in Methuen Police Contracts Investigative Findings

Online

Phone

Address

| Date published: | December 23, 2020 |

|---|