- Scientific name: Falco peregrinus

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Special Concern (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus)

The peregrine falcon is the fastest bird on earth, capable of diving from great heights at speeds of up to 390 km per hour (242 miles per hour). It is a beautiful raptor with long, pointed wings and a long, slightly rounded tail. Adults have a bluish-gray to slate-gray backside and a buffy white underside interspersed with black. Adults also possess a black crown, black moustache-like markings or “sideburns,” a white throat, a dark bill with a prominent yellow fleshy base (or cere), and yellow legs and feet. Immature peregrines have a brown backside and heavily streaked underside. Peregrines are medium-size falcons; males are slightly smaller than a crow 0.4 to 0.45 m (15 to 18 in) in length with a wingspan of 0.9 to 1.1 m (35 to 42 in), while females are slightly larger than a crow, reaching a length of 0.45 to 0.5 m (18 to 20 in) with a wingspan of 1.1 to 1.2 m (42 to 48 in). In the fall and winter, especially along the coast, smaller merlins and larger gyrfalcons (rare) may be confused with peregrine falcons.

Life cycle and behavior

Most peregrine falcons first nest at 2 or 3 years old, but a few (particularly males) will breed as one-year-old birds when they are still in their juvenile plumage. Once established, the adults will remain in the same territory year-round and generally live about 10 years. The longest known life span of a peregrine falcon in Massachusetts was achieved by the second male to occupy the Customs House tower territory in downtown Boston. This bird lived to be 17 years old and raised 50 chicks. Although this pair nested on the Customs House in most years, they also nested on the MacCormack Post Office and Courthouse Building in Post Office Square and in the 32nd floor balcony garden of the Federal Reserve Bank. This illustrates the species’ tendency to nest in the same spot year after year but to occupy alternate nest sites within their territory in some years.

By March 1, the adult pair has chosen their nest site for the season and are spending a lot of time in and around the nest site. Four, rarely five, eggs are laid around the beginning of April and the chicks hatch in early May after a 28-day incubation. The chicks fledge (leave the nest) at about 7 weeks of age in mid-June and become independent of their parents by the beginning of August. In their first fall and winter, most of the young falcons disperse to other areas of Massachusetts, particularly along the coast, while others disperse throughout the northeastern states where they will eventually nest. A very small number of young birds will disperse as far south as Florida but will return to the Northeast again in the spring and never move that far south again.

Peregrines are specially adapted to capture birds in flight. Their best-known hunting strategy is to soar high over their territory and wait for a bird to fly past far below. Once a target has been chosen, they do several strong wing beats to pick up speed and drop straight down into a controlled dive called a stoop. It is during this maneuver that they can attain their record speed. The small bird flying below does not usually even know that it has been targeted. The peregrine will strike its prey hard enough to kill it and streak right past. The falcon then pulls out of its dive and catches the falling prey. It is a spectacular scene to watch and is what has made the peregrine falcon so prized in falconry since medieval times.

In Massachusetts, the most frequent prey species are blue jay, European starling and rock dove (pigeon). Other common prey species include red-winged blackbird, common grackle, American robin, mourning dove, northern flicker, chimney swift, house finch, cedar waxwing, American woodcock, and both black-billed and yellow-billed cuckoo.

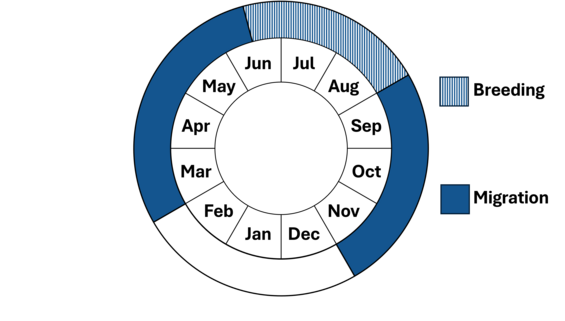

Figure 1. Phenology in Massachusetts. This is a simplification of the annual life cycle. Timing exhibited by individuals in a population varies, so adjacent life stages generally overlap each other at their starts and ends.

Population status

In the 1930s and 1940s, there were probably about 375 nesting pairs east of the Mississippi River in the United States. Fourteen pairs nested on cliffs in Massachusetts. In 1948, the Massachusetts State Ornithologist, Archie Hagar, discovered that the pair nesting on Rattlesnake Ledge on the western shore of the Prescott Peninsula on the newly created Quabbin Reservoir had broken their eggs for no apparent reason. This observation was the first indication of the effects of the pesticide DDT. Intended for the control of agricultural insect pests, this pesticide passed up the food chain from insects through songbirds to peregrine falcons, and other predatory species, where it became concentrated. The most significant impact to the falcons was that they laid thin-shelled eggs that broke under the weight of incubation, leaving no young to replace the adults when they eventually died. By 1966, not a single nesting pair remained in the eastern United States. The last historically active nest in Massachusetts was on Monument Mountain in Great Barrington in 1955.

With the ban of DDT in the U.S. in 1972, the stage was set for restoration efforts to begin. The Peregrine Fund, a non-profit organization originally based at Cornell University in New York, began to captive-breed and release young peregrine falcon chicks. Two of the earliest release sites were on a tower at Mass Audubon’s Drumlin Farm in Lincoln (1975) and on the cliffs of Mount Tom in Holyoke (1976-1979). Unfortunately, none of these birds survived to breed. With the creation of the “Nongame and Endangered Species Program” in 1983, funded largely by voluntary donations on the state income tax form, peregrine falcon restoration became the Program’s first new project. Young falcons were released on the roof of the McCormack Post Office and Court House Building in downtown Boston in 1984 and 1985. This effort led to the first modern Massachusetts nest in 1987.

Eventually, more than 6,000 captive-born peregrine falcon chicks were released across the country by several organizations. The number of nesting pairs continued to grow to the point that on August 25, 1999, the peregrine falcon was officially removed from the federal list of endangered and threatened species, having skipped the status of threatened. Surveys near the time of federal delisting documented over 2,000 nesting pairs in the U.S. (2002), over 400 in Canada (2002) and about 170 in Mexico (1995). In Massachusetts, there were 14 known territorial pairs in 2007. This was the first year that the numbers of pairs had returned to their pre-DDT levels. This number had increased to about 30 nesting pairs by 2015 and 44 nesting pairs in 2024. Peregrines are now nesting at many of the historic cliff nest sites, but the population increase has been driven by the significant increase in nesting opportunities on man-made structures, such as buildings and bridges.

Distribution and abundance

The peregrine falcon is one of the most widely distributed birds in the world, inhabiting every continent except Antarctica. Birds that breed in the North American Arctic move through the lower 48 states as they migrate to their non-breeding grounds as far as South America. The Atlantic coast is a major migratory pathway for the species.

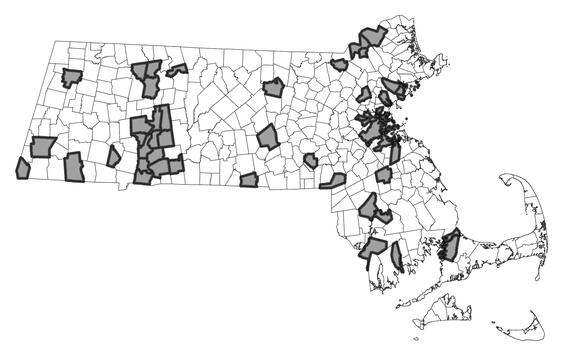

Distribution in Massachusetts. 1999-2024. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Peregrine falcon on a beach

Historical peregrine nesting sites (eyries) within Massachusetts were located on rocky cliffs. Of the 14 historical cliff nest sites, peregrines have returned to many including Mount Tom (Easthampton), Mount Sugarloaf (Deerfield), Farley Cliffs (Erving), Monument Mountain (Great Barrington), Pettibone Falls (Chester), and Hanging Mountain (Sandisfield). Peregrines also nest on the cliffs of quarries in Holyoke, West Roxbury, Saugus, Peabody, and Swampscott.

However, now peregrines nest most frequently on man-made structures such as buildings and bridges. Peregrines are unusual among raptors in that they do not bring any materials to construct a nest. They simply find a cliff site with accumulated soil or gravel and scrape out a shallow depression in which to lay their eggs. Sometimes, they will lay their eggs in an unused nest of another species, usually a common raven, but also red-tailed hawk, and on one occasion an osprey (Quincy). Since man-made structures do not have natural accumulations of soil, the female peregrine will lay her eggs on rock dove (pigeon) nests and accumulated droppings, and sometimes simply on bare steel. Nest failure at such sites is high. However, the placement of a nest box or nest tray filled with a few inches of pea gravel provides an excellent nest site.

Peregrine falcons now nest on buildings in Boston, Chelsea, Cambridge, Watertown, Lawrence, Lowell, Worcester, Amherst, and New Bedford. They nest on bridges in Charlestown, Fall River, West Springfield, and Northampton. One pair nests on a cell tower in Brockton, and the pair in Quincy originally nested on the 400-foot-tall Goliath Crane in the Quincy Shipyard, until the crane was dismantled and shipped to Romania.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

Threats to this species include collisions with building (especially for urban nesting birds) and aircraft around airfields where they may be attracted to the surrounding habitat. Contaminants (e.g., Mercury) continue to be a concern and have the potential to reduce reproductive output. Disease is another threat, and similar to other avian predators, they have been disproportionately impacted by the strain of highly pathogenic avian influenza (HPAI) that arrived in North America in late 2021. They contract the virus by consuming infected prey items.

Rodenticides (e.g., Second Generation Anticoagulant Rodenticides - SGARs) move up food chains and pose a threat to raptors when they consume prey that have ingested these chemicals. As a result, SGARs have been found in a high percentage of raptors that have been tested for them in Massachusetts, and it is well documented that they can kill individual raptors. However, their population-level impacts on raptors remain largely unknown.

Conservation

MassWildlife continues to work with partners (e.g., MassDOT) to deploy nesting structures on buildings and bridges to promote successful falcon nesting. Educational outreach is being conducted to reduce disturbance at nest sites during the breeding season.

Conduct research to better understand the impacts of highly toxic rodenticides (e.g., SGARs) to raptor populations. Promote an integrated pest management approach that emphasizes the use of alternative pest control measures whenever possible to reduce negative impacts to wildlife. Coordinate with other state agencies to improve tracking and reporting of rodenticides found in wildlife and develop outreach materials for the public.

References

Walsh, J. and W.R. Petersen. 2013. Massachusetts Breeding Bird Atlas 2. Massachusetts Audubon Society and Scott & Nix, Inc.

White, C. M., N. J. Clum, T. J. Cade, and W. G. Hunt (2024). Peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus), version 1.1. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman and M. G. Smith, Editors). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bow.perfal.01.1

Contact

| Date published: | April 24, 2025 |

|---|