- Scientific name: Charadrius melodus

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Threatened (MA Endangered Species Act)

- Threatened (US Endangered Species Act)

Description

Piping plover (Charadrius melodus)

The piping plover measures 17-18 cm (about 7 in) long. It has sandy-colored plumage on its upperparts, which gives it excellent camouflage in its beach habitat. It has a white breast, forehead, cheeks, and throat; a black band on the forecrown, extending from eye to eye; and a black breastband, which may be discontinuous. The tail is white at the base and tip, but dark in the middle. It has yellow-orange legs. In summer, its short bill is yellow-orange with a black tip; in winter, the bill is completely black. In general, females have less prominent forecrown and breast bands and darker bills than males. The piping plover runs in a pattern of brief starts and stops; in flight, it displays a pair of prominent white wing stripes. Its call is a series of musical, piping whistles.

The piping plover is similar to the semipalmated plover (Charadrius semipalmatus) in size, shape, and plumage pattern, and they are found in similar habitats. However, the semipalmated plover is a darker brown and has much more black on its head than the piping plover. The semipalmated plover does not breed in Massachusetts but is present on sandy beaches and intertidal flats from late July to early September during its southward migration. The piping plover is also similar to another plover species that nests in Massachusetts, the killdeer. However, the killdeer is much larger, darker brown, and has a double breastband. While the killdeer does nest on beaches, it is more commonly found at inland locations. Reports in Massachusetts of plovers nesting on rooftops, or in inland parking lots, meadows, agricultural lands, athletic fields, golf courses, commercial areas, and other locations with open, grassy grounds are never piping plovers and are virtually certain to be killdeer.

Life cycle and behavior

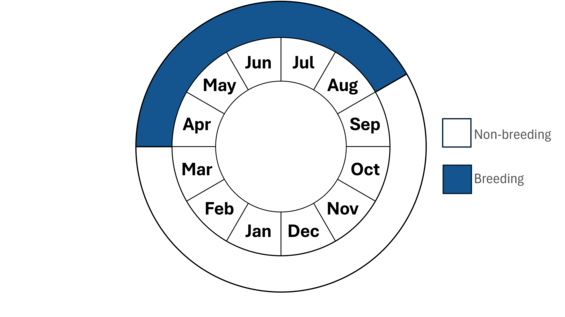

Figure 1. Phenology of the piping plover in Massachusetts. This is a simplification of the annual life cycle. Timing exhibited by individuals in a population varies, so adjacent life stages generally overlap each other at their starts and ends.

As soon as piping plovers return to their breeding grounds in Massachusetts in late March or April, the males begin to set up territories and attract mates. The earliest nests are laid in mid-April and the latest in early August; the peak of laying is the first few weeks of May. Chicks follow a month after laying. Fledged piping plover young leave the nesting area soon after becoming flight-capable. Piping plovers begin to migrate southward between late July and early September, although occasional stragglers remain behind until late October.

Territoriality. Territorial rivalry between males is very strong; adjacent male piping plovers mark off their territories by running side by side down to the waterline. Each bird takes turns, one running forward a few feet, then waiting for the other to do likewise. The nesting pair will confront (chase, peck, bite, or beat with wings) any intruding piping plover which approaches the nest. Male piping plovers also defend feeding territories encompassing beach front adjacent to the nesting territory. Intruding plover chicks from neighboring territories are chased, pecked, and occasionally killed, but chicks of neighboring pairs sometimes forage together and are brooded together.

Pair bond and parental care. Pairs are typically monogamous during a breeding season but will often change mates from year to year. Courtship consists of a ritualized display by the male, who flies in ovals or figure-eights around a female, then displays on the ground by bowing his head, dropping his wings, and walking in circles around the female. The male also scrapes shallow depressions in the sand at potential nest sites, while tossing shells and pebbles. The female then chooses one of these nesting sites, usually in a flat, sandy area. Before copulation, the male rises into an erect posture and high-steps rapidly with feet. Both parents incubate the eggs and brood the chicks. Adult birds often change mates from year to year.

Nests and eggs. The nest is a shallow depression, often lined with shell fragments and small pebbles that may aid in camouflaging the eggs. Nests of neighboring pairs are usually at least 60 m (200 feet) apart. Female piping plovers typically lay four eggs per clutch, one egg every other day over a week’s time. The eggs are pale buff in color with fine, blackish spots that are usually distributed evenly across the egg. Eggs are incubated for 26-28 days and all hatch within 4 to 24 hours of each other. Nest loss is common and adults may lay up to five nests per season if the earlier ones fail. Primary causes of nest loss in Massachusetts are predation, overwash, and abandonment.

Young. Chicks are downy and precocial. They leave the nest within hours after hatching and may wander hundreds or thousands of meters before they become capable of flight. When threatened by predators or human intruders, young run or lie motionless on the sand while their parents flutter on the ground, pretending to have broken wings in an effort to distract the intruder from the chicks. Parents brood the chicks for 3 to 4 weeks. Chicks fledge 4 to 5 weeks after hatching. With rare exceptions, adults do not renest after losing chicks and just one brood per season is raised to fledging.

Diet and foraging. Atlantic Coast piping plovers feed on marine worms, mollusks, insects, and crustaceans. They forage along in the intertidal zone, in vegetated dunes, on tidal flats at low tide, and in wrack (seaweed, marsh vegetation, and other organic debris deposited by the tides) along the beach. Foraging behavior consists of rapid running bouts interspersed with pecks, or vibrating one foot on the ground, finally pecking at a food item detected in the sand.

Demography and survival. Adults can start breeding at one year old, but the proportion that do so is uncertain. The oldest documented wild piping plover was encountered alive at a minimum age of 17 years and 4 months.

Population status

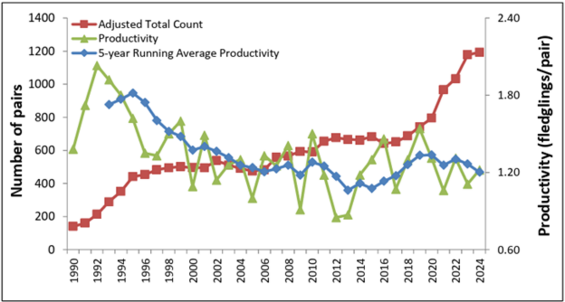

There are three populations recognized by the US Fish and Wildlife Service: Northern Great Plains, Great Lakes, and Atlantic Coast. The Atlantic Coast population of piping plovers, to which Massachusetts birds belong, is listed as Threatened at both the state and federal levels. In Massachusetts, numbers have increased nearly tenfold since the population was federally listed in 1985 (Figure 2). In 2024, 1,193 pairs nested at about 220 sites in Massachusetts, which has the largest breeding population of piping plovers along the Atlantic Coast.

Figure 2. Piping plover abundance (adjusted total count) and productivity (fledglings/pair) in Massachusetts, 1990 – 2024.

Distribution and abundance

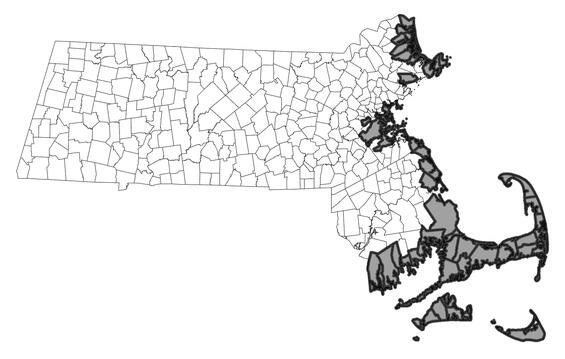

During spring and summer, the Atlantic Coast population of the piping plover nests from Newfoundland south to North Carolina. Piping plovers nest throughout coastal Massachusetts and have even expanded to urban shorelines. Wintering locations are incompletely known outside of the U.S. Wintering piping plovers have been found from North Carolina to Florida, the Gulf of Mexico, and the Caribbean, including Cuba and the Bahamas. The other populations of piping plovers nest along rivers and lakes on the Northern Great Plains and along the shores of the Great Lakes, with wintering recorded along the Gulf of Mexico and the southern Atlantic Coast.

Adult birds often return to the same nesting area every spring. Young birds may nest anywhere from a few hundred feet to many miles from where they were hatched.

Distribution in Massachusetts. 1999-2024. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Piping plovers in Massachusetts nest on sandy coastal beaches that are relatively flat and have sparse vegetation due to periodic scouring by storm tides. Nests are often in a band between the high tide line and the foot of the dunes; also in vegetated dunes, eroded areas (“blowouts”) in between and behind dunes, and areas where dredge spoils have been deposited. Piping plovers may nest within least tern colonies.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Adult piping plover and its chick in sparsely vegetated sandy habitat.

Threats

Habitat loss and degradation: Nesting habitat is threatened by development, shoreline hardening (which interferes with natural coastal processes), dune-building (which changes beach slope), rising sea levels, and increasing frequency and intensity of storms due to climate change.

Disturbance at nest sites. Piping plovers are regularly threatened by beach management activities such as beach raking, and human recreation, including pedestrians and their dogs, over-sand vehicles, and fireworks.

Predators. The primary predators of piping plovers in Massachusetts are coyotes, crows, and gulls, but also foxes, skunks, domestic dogs, rats, feral cats, raptors such as American kestrels, and common grackles, among others. Because in Massachusetts most piping plovers nest on mainland beaches accessible to both mammalian and avian predators, predation rates of eggs and chicks are high, contributing to frequent renesting.

Climate change: In addition to climate-induced habitat loss from rising sea levels and storms, changes in prey species and availability may occur.

Wind farms: The construction and operation of offshore wind turbines, which are poised to proliferate in the Northeast, may cause collision mortality as plovers migrate over the ocean.

Plastics: Plastic trash in the environment poses a threat as it can be mistaken as food by seabirds and shorebirds and ingested or cause entanglement. Ingested plastics, common for seabirds, can block digestive tracts, cause internal injuries, disrupt the endocrine system, and lead to death. Entanglement from fishing gear and other string-like plastics can cause mortality by strangulation and impairing movements.

Conservation

Since the 1970s, most sites have been fenced and posted with signs to discourage human intrusion into colonies. At many sites, piping plover and least tern protection and management is integrated due to the species similar nesting habitat requirements and threats. Because of the piping plover’s propensity for nesting on mainland and barrier beaches, disturbance by humans and predators remains a chronic problem. The principal conservation challenge confronting wildlife managers in protecting piping plovers is to maintain adequate separation between people and plovers to enable the birds to successfully reproduce. Restricting access to nesting areas through installation of post-and-string (“symbolic”) fencing is crucial. Humans and their dogs directly and indirectly harm nesting birds by: keeping adult birds off nests, contributing to egg and chick mortality due to environmental exposure and predation; stepping on eggs and chicks; and in the case of dogs, killing eggs and chicks. Over-sand vehicles crush plover eggs and chicks and destroy habitat; ruts created by tires trap chicks, preventing normal movements and further exposing them to interactions with vehicles. Garbage left on the beaches by humans may attracts predators to colonies. Given the habitat that the piping plover selects, intensive and ongoing management will always be necessary to adequately shield them from disturbance. Efforts to limit coastal development and ensure that other coastal activities are conducted in a manner that does not harm plovers or their habitat are also critical to protecting the viability of the state’s population. Avoid or recycle single-use plastics and promote and participate in beach cleanup efforts.

Knowledge of distribution, abundance, and ecology of wintering piping plovers is incomplete. Before whole life-cycle conservation will be feasible, substantial research is necessary to fill these knowledge gaps.

Acknowledgments

Beach-nesting birds in Massachusetts are protected and managed by an extensive network of highly dedicated and conservation-minded landowners, individuals, organizations, and agencies. The birds’ successes are their successes.

References

Bird Banding Laboratory. North American Bird Banding Program Longevity Records. Version 2023.2. Eastern Ecological Science Center. US Geological Survey. Laurel, MD.

Blodget, B.G., and S.M. Melvin. Massachusetts Tern and piping plover Handbook: A Manual for Stewards. Westborough, MA: Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, 1996.

Elliott-Smith, E. and S. M. Haig (2020). Piping plover (Charadrius melodus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Contact

| Date published: | April 23, 2025 |

|---|