- Scientific name: Calidris cantus

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Threatened (MA Endangered Species Act)

- Threatened (US Endangered Species Act)

Description

Red knot (Calidris cantus)

Red knots are a stocky, medium-sized shorebird. Adults are 23-25 cm long (9-10 in), weigh on average 135 g (4.8 oz), and have a wingspan of 45-54 cm (18-21 in). During spring migration, it has a distinctive (but pale) rusty-red breast (pictured), but it is a dull gray when it migrates back through Massachusetts in late summer and fall on its way to the wintering grounds. Calls include a low knut, also a low tooit-wit or wah-quoit.

Life cycle and behavior

Breeding: Red knots arrive at their breeding grounds in late May and early June. Males arrive before females and begin establishing territories and preparing nest scrapes. Pairing occurs within a few days of female arrival at the breeding colony. Red knots lay one brood per season with four eggs per clutch. The incubation period is 21-23 days and both adults share incubation duties. Chicks are precocial and highly mobile within 24 hours of hatching. Families quickly move to lower, wetland habitats. Females leave breeding grounds within a few days of hatch, and the males stay behind for parental care. Red knot chicks forage for themselves, while the male parent provides defense from predators. Red knot males will alert chicks and will fly at and chase predators. It is unknown when parental care of young ends, but studies have found broods as young as 15 days old without attending parents.

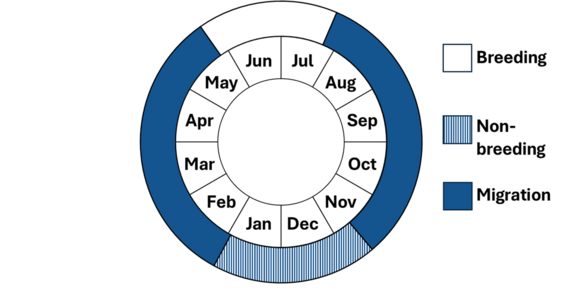

Migration: Red knots are known as “jump” migrants with few stopover sites. They may have flights of up to 8,000 km (5,000 mi) and rely on phenological food resources to fuel their long-distance migration. Red knots have a protracted migratory season relative to other shorebirds. Some populations begin their northbound migration in late January and February, while other populations have peak migration numbers from March to May. Southbound migration occurs in waves, starting with females and failed nesters in mid-July and early August. Males from successful nests begin migrating in early August, and juveniles are first seen at stopover sites in mid-August. Another wave of migrating adults happens in late August and early September.

Diet: During the breeding season, red knots feed on insects, spiders, small crustaceans, snails, and worms. Their main prey item is adult and larval Diptera. During the non-breeding season, red knots feed on marine invertebrates and amphipods, focusing particularly on small mollusks. Their diets in tropical regions are more generalist, and they take on an opportunistic foraging strategy to account for unpredictable prey sources. A key migratory prey source occurs in Delaware Bay during the northbound migration. The annual horseshoe crab spawning produces a superabundance of eggs, and red knots rely on this food resource prior to their arrival at the breeding grounds.

Demography and Survival: Age at first breeding is unknown and possibly variable but is likely no earlier than two years old. Annual adult survivorship varies but was as low as 0.564 during substantial population declines. Maximum recorded life span is 19 years.

Phenology in Massachusetts. This is a simplification of the annual life cycle. Timing exhibited by individuals in a population varies, so adjacent life stages generally overlap each other at their starts and ends.

Population status

The International Union of Conservation of Nature lists the red knot as near threatened. There are an estimated 2,000,000–3,000,000 mature individuals globally. The current population trend is decreasing. Studies on two significant red knot subpopulations (Canadian breeding islandica and rufa) are showing substantial decline, but a recent study demonstrated that the overwintering islandica subpopulation has a stable population trend. The contradictory studies show decreases in other subpopulations, which provides support to a variable but decreasing global population trend.

Historically, there were records of thousands of red knots along the Massachusetts shoreline during both spring and fall. Although few knots are currently found in Massachusetts during spring migration (May-June), high numbers of birds continue to stop-over in the state during fall migration (July-September). Interestingly, the reported numbers of red knots using outer Cape Cod during fall migration has remained steady over the last 50 years, while numbers of knots using the mainland has declined dramatically over this same period.

Distribution and abundance

The red knot is an Arctic breeder with nesting areas in northern Canada, Alaska, Greenland, and northern Russia. Their non-breeding range is cosmopolitan and non-breeding red knots are found on the coastlines of six continents. The largest wintering population is currently in Tierra del Fuego and coastal Patagonia. Some birds winter along the Gulf of Mexico and occasionally are found as far north as Massachusetts on the Atlantic coast.

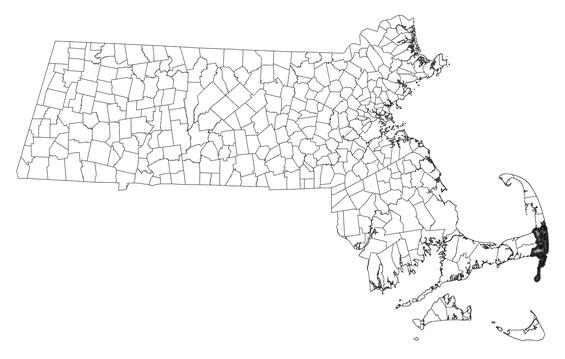

There are no nesting records of this species in Massachusetts. Red knots use coastal areas in Massachusetts as migratory stopover locations for foraging during spring and fall migration as they move between their wintering and breeding grounds. Major historical migratory stop-over locations for red knots in Massachusetts include beaches on outer Cape Cod and mainland beaches along West Cape Cod Bay.

Distribution in Massachusetts. 1999-2024. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

As is the case for many species of shorebirds, red knots use starkly different habitats during the breeding and non-breeding periods. Knots nest on sparsely vegetated (<5%) tundra habitat, often within 50 km (31 mi) of the coast and characterized by ridges or slopes with stunted willow. During migration, red knots generally use sandy beaches, but they can be found on peat banks, salt marshes, tidal mudflats, and lagoons. Habitat used on the wintering grounds is like that during migration.

During migration and wintering periods, red knots use sandy beaches and intertidal areas in Massachusetts and feed on a variety of bivalves and crustaceans. It is uncertain if spring migrants in Massachusetts seek out and feed on horseshoe crab eggs, as occurs with the continentally significant concentrations of red knots along Delaware Bay beaches in southern New Jersey and eastern Delaware in May. During periods of high tide, when the intertidal zone is not exposed, knots can be found roosting in groups higher on the beach.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

The red knot’s tendency to congregate in large numbers at limited staging sites increases potential impacts from traditional threats. The subspecies (rufa) of the red knot that migrates through eastern North America has declined by 75% since the 1980s. This drop in the population is thought to primarily be a result of a reduction in the abundance of horseshoe crab eggs (from overharvesting) in Delaware Bay coinciding with the red knot migration. Horseshoe crab eggs are the primary food source at this extremely important migratory stop-over location, where red knots stage for up to several weeks when they put on critical fat reserves for their next migratory flight. However, the extent to which declines in horseshoe crabs in Massachusetts have affected red knots is uncertain. Habitat loss and degradation due to land reclamation and development is also a concern.

Other threats to this species include loss of unregulated hunting in the Caribbean and northern South America, oil spills, and climate change. Red knots are arctic breeders, and anticipated impacts of rising temperatures will likely be greater at higher latitudes. Sea level rise will likely be greater along temperate coastlines, which is important migratory habitat.

Plastic trash in the environment poses a threat as it can be mistaken as food by seabirds and shorebirds and ingested or cause entanglement. Ingested plastics, common for seabirds, can block digestive tracts, cause internal injuries, disrupt the endocrine system, and lead to death. Entanglement from fishing gear and other string-like plastics can cause mortality by strangulation and impairing movements.

Red knot (Calidris canutus)

Conservation

Many shorebird conservation organizations highlight that identifying and protecting major migratory sites and winter areas are critical management goals for red knots. Additionally, the protection of key prey resources (e.g. limiting horseshoe crab harvests) are top priorities for managers. Conservation efforts in Argentina include the management and protection of migratory habitats, as well as successful public awareness campaigns. Thus far, global management and conservation actions have had limited success, although continued protections and efforts are needed. Avoid or recycle single-use plastics and promote and participate in beach cleanup efforts.

Future research needs include demographic modeling, identification of breeding and wintering sites, quantifying annual breeding success, and ecological management of horseshoe crab fisheries.

References

Baker, A., P. Gonzalez, R. I. G. Morrison, and B. A. Harrington. Red Knot (Calidris canutus), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). 2020. Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi-org.silk.library.umass.edu/10.2173/bow.redkno.01

BirdLife International. Species factsheet: Red Knot Calidris canutus. 2024. https://datazone.birdlife.org/species/factsheet/red-knot-calidris-canutus

Forbush, E.H. 1925. Birds of Massachusetts and Other New England States, Volume II. MA Dept. of Agriculture.

Harrington, B. A. 2001. Red Knot (Calidris canutus). In The Birds of North America, No. 160 (A. Poole and F. Gill, eds.). The Birds of North America, Inc., Philadelphia, PA.

Harrington, B.A., N.P. Hill, and B. Nikula. 2010. Changing use of migration staging areas by Red Knots: An historical perspective from Massachusetts. Waterbirds 33(2): 188-192.

Rufa Red Knot Ecology and Abundance. Supplement to Endangered and Threatened Wildlife and Plants; Proposed Threatened Status for the Rufa Red Knot (Calidris canutus rufa). Docket No. FWS-R5-ES-2013-0097; RIN 1018-AY17.

Veit, R., and W.R. Petersen. 1993. Birds of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Audubon Society, Lincoln, Massachusetts.

Contact

| Date published: | April 3, 2025 |

|---|