- Scientific name: Williamsonia lintneri

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Threatened (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Male ringed boghaunter

The ringed boghaunter (Williamsonia lintneri) is a small, delicately built dragonfly (order Odonata, suborder Anisoptera) in the family Corduliidae (the emeralds). It has a dark brown body, smoky blue-grey eyes, and pale orange-brown face and mouth parts. The most distinctive feature is a series of dull orange rings encircling all but the first and last of the ten abdominal segments. Females are similar to males but have thicker abdomens and much shorter terminal appendages at the tip of the abdomen.

Ringed boghaunters range from 30-34 mm (1.2-1.4 in) in length, of which almost two-thirds is abdomen. The wings are about 2.2 cm (0.87 in) long and hyaline (transparent and colorless), except for a very small patch of amber at the base of the wings. The nymphs, which were undescribed until 1970 (White and Raff 1970), are about 15-18 mm (0.7 in) in length when fully developed (Tennessen 2019).

The genus Williamsonia comprises just two species, both found only in northeastern North America. The ebony boghaunter (W. fletcheri) is very similar in appearance, occupies similar habitats, and shares many of the same behavioral traits. However, the ebony boghaunter flies slightly later in the season (mid-May through mid-June), the male has bright green eyes when mature (the female has grey eyes), and the ebony boghaunter has only one or two obvious rings at the base of the abdomen; the rest of the abdomen is dark. The male frosted whiteface (Leucorrhinia frigida) is also very dark and similar in size but has a white face and a frosty white area at the base of the abdomen. The Hudsonian whiteface (Leucorrhinia hudsonica) also flies early in the season, occupies the same habitat, shares the tendency to alight on roads and paths near wooded areas, and is much more abundant. It is similar in size, but is more colorful with red, orange, or yellow on the thorax, and abdominal markings which are triangular as opposed to ring-like in the ringed boghaunter. Additionally, the face of the Hudsonian whiteface is white instead of orange-brown. Two other dragonflies, the common baskettail (Epitheca cynosura) and Uhler’s sundragon (Helocordulia uhleri), both have flight seasons that overlap the ringed boghaunter’s and have yellow-orange abdominal markings, but they are larger than ringed boghaunters, do not have ringed abdominal markings, usually have dark markings at the base of the wings, and rarely perch on the ground or tree trunks.

Life cycle and behavior

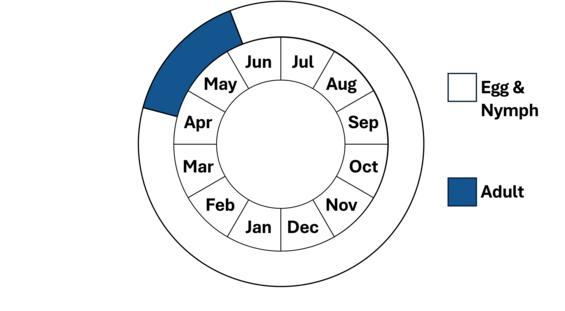

Note, nymphs are present year-round.

The egg and nymph life stages of the ringed boghaunter are fully aquatic. The cryptic nymphs are predators feeding mostly on small invertebrates and are usually highly localized and clustered, sometimes at high densities (Tennessen 2019). Nymphs undergo several molts (instars) for at least 2 years until they are ready to emerge as winged adults. Nymphs emerge up onto emergent vegetation, exposed substrates, or tree trunks. When the nymph reaches a secure substrate, the adult begins to push itself out of the exoskeleton. As soon as the abdomen and wings are fully expanded, the adult takes its first flight. This maiden flight usually carries the individuals up into surrounding forest or other areas away from water, where they spend several days maturing and feeding and are somewhat protected from predation and inclement weather. Nymphs emerge from the water in April to transform into winged adults, which have a brief flight season extending only from late April or early May to early June. Because ringed boghaunters emerge from the water so early in the year (they are among the first dragonflies to appear), they spend much of their time basking in warm, sunny spots. Adult ringed boghaunters are not believed to be territorial and spend most of their time in the woodlands, seeking out sunny openings through the forest canopy, where they alight on tree trunks, rocks, trails, and roads. Unlike other emeralds, they typically perch flat to the ground or other substrate. They are not very wary and will even land on light-colored clothing. Their tendency to stay in the forest may reduce harassment and predation by birds and larger, more aggressive dragonfly species. However, their dark coloration and low flight habit makes them very inconspicuous, even in flight, and they are easily overlooked. Like all dragonflies, the ringed boghaunter is entirely predatory and feed on small insects.

Breeding in Massachusetts probably occurs in May. Males seek females from staging areas adjacent to breeding wetlands, clasp to a female, and fly off into the surrounding forested uplands to mate. Following mating oviposition occurs with female intermittently tapping the surface of water, while the male hovers and perches nearby. Females have been observed ovipositing into shallow troughs and pools of submerged sphagnum.

Ringed boghaunters typically first appear in late April, peak in May, and are on the wing into late May or early June.

Distribution and abundance

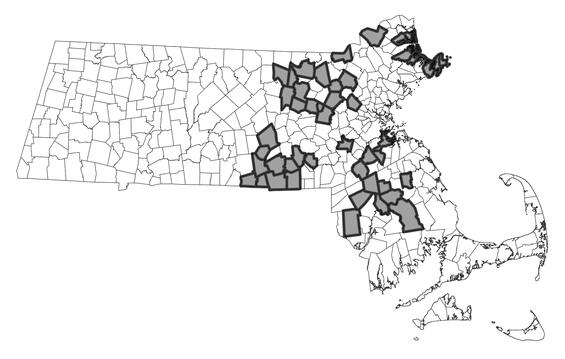

The ringed boghaunter is very local in distribution and are considered glacial relicts. The range extends from southwestern Maine west through southern New England into New York and New Jersey. Recently, the species has been discovered at sites in Wisconsin and Michigan, a significant westward extension of the known range. Most known sites for the species occur in a band from southern New Hampshire south through eastern Massachusetts into Rhode Island. In Massachusetts, the species has been observed in the Nashua, Merrimack, Concord, Ipswich, Charles, Neponset, Taunton, and Cape Cod watersheds. Recent efforts have identified several new occupied wetlands within the above watersheds; however, occupancy of several historical wetlands may be lost. Observed abundances are typically low (i.e., <5 individuals) and may reflect small population sizes that inhabit its smaller wetland habitats or low detection probability at the time of sampling. However, there are several sites in that support relatively high abundances (>50 individuals) annually and is likely correlated to the amount of suitable habitat, which are mostly on protected land.

The ringed boghaunter is listed as a Threatened species in Massachusetts. As with all species listed in Massachusetts, individuals of the species are protected from take (picking, collecting, killing, etc.) and sale under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

The ringed boghaunter is found primarily in acidic sedge fens and sphagnum bogs, with soupy sphagnum pools or troughs, surrounded by woodlands. However, the specific habitat requirements of the ringed boghaunter are not well understood, as it seems to be absent from many apparently appropriate sites. The females oviposit and the larvae develop in shallow pools 15-30 cm (6-12 in) in depth, among sphagnum pools or sedge tussocks. These bog mats are suitable as habitat only if they possess open pools and are not choked with heaths. An important requirement for suitable habitat is the presence of surrounding woodlands, which are used as resting places and often as mating sites. All known breeding sites have at least some sphagnum (Sphagnum spp.). Other plants often associated with ringed boghaunter habitats include three-way sedge (Dulichium arundinaceum), highbush blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum), sheep laurel (Kalmia angustifolia), leatherleaf (Chamaedaphne calyculata), and Atlantic white cedar (Chamaecyparis thyoides). Many sites inhabited by ringed boghaunters are quite small (< 1 hectare), may dry up in the summer, and do not have fish.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Examples of ringed boghaunter habitat dominated by Sphagnum moss floating or submerged in water and sometimes with an abundance of sedges.

Threats

The primary threat to the ringed boghaunter is wetland, riparian, and upland habitat destruction through physical alteration or pollution. Much of its former habitat has been destroyed by urbanization and consequently, several historically documented populations in Massachusetts appear to be extirpated. Artificial changes in water level and various forms of pollution, such as agricultural and road runoff, septic system failure, and insecticides, are all potential threats.

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

Surveys should continue to target known sites and new wetlands to determine ringed boghaunter detection and occupancy rates. Increased effort over the past five years has identified new occupied sites and has the potential to inhabit other wetlands. Surveys should target adults in basking and breeding habitats, where the species is mostly likely to be detected. The species is most often observed away from wetlands on nearby dirt roads, trails, or sunny patches within the forest. Later in the flight period, the species may be best surveyed in wetlands where breeding might occur. Multiple site visits (e.g., >3) are likely required to detect this species because of its rarity and its difficulty to capture by net or camera. Prioritized sites should be monitored at least every 5 years to document changes in occupancy and habitat conditions.

Management

Protection of wetlands and its surrounding upland habitat is crucial for ringed boghaunter persistence in Massachusetts. Upland habitats adjoining the breeding sites should be maintained for roosting, hunting, and for newly emerged adults that are more susceptible to mortality from predation and inclement weather. Development of these areas should be discouraged, and the preservation of remaining undeveloped uplands should be a priority. Alternatives to commonly applied road salts should tested to minimize freshwater salinization. Other actions to improve or prevent habitat degradation include reduction of nutrient, agricultural and road runoff; minimization of water level alteration and groundwater withdrawals particularly during drought periods; prevention and management of nonnative aquatic vegetation; limitation and enforcement of off-road vehicles in wetland habitat; and upland connectivition between ponds.

Research needs

Research effort is needed to estimate occupancy and detection rates for this species as species detection may be low and inhabit other suitable wetlands on the landscape. Through standardized surveys, more effort is needed to refine species habitat requirements. The effects of climate change on ringed boghaunter and climate resistance of its aquatic habitat, including water temperature and water quantity, warrant further investigation. Furthermore, confirmation of known and identification of source and sink wetlands are needed to accurately assess the species risk to anthropogenic threats.

References

Brown, V.A. 2020. Dragonflies and Damselflies of Rhode Island. Rhode Island Division of Fish and Wildlife, Department of Environmental Management, West Kingston RI.

Biber, E. 2002. Habitat analysis of a rare dragonfly (Williamsonia lintneri) in Rhode Island. Northeastern Naturalist 9(3): 341-352.

Carpenter, G. 1993. Williamsonia lintneri, a phantom of eastern bogs. Argia 5(3):2-4.

Dunkle, S.W. 2000. Dragonflies Through Binoculars. Oxford University Press.

Howe, R.H., Jr. 1923. Williamsonia lintneri (Hagen), its history and distribution. Psyche 30:222-225.

Lam, E. Dragonflies of North America. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2024.

Needham, J.G., M.J. Westfall, Jr., and M.L. May. 2000. Dragonflies of North America. Scientific Publishers.

Nikula, B., J.L. Ryan, and M.R. Burne. 2007. A Field Guide to the Dragonflies and Damselflies of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program.

Paulson, D. Dragonflies and Damselflies of the East. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Soltesz, K. 1996. Identification Keys to Northeastern Anisoptera Larvae. Center for Conservation and Biodiversity, University of Connecticut.

Tennessen, K. Dragonfly Nymphs of North America: An identification guide. Springer, 2019.

Walker, E.M. 1958. The Odonata of Canada and Alaska, Vol. II. University of Toronto Press.

White, H.B., and R.A. Raff. 1970. The nymph of Williamsonia lintneri (Hagen) (Odonata: Corduliidae). Psyche 77:252-257.

Contact

| Date published: | April 10, 2025 |

|---|