- Scientific name: Sorex dispar

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Special Concern (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

DeGraaf, R.M. and D.D. Rudis. 1986. New England Wildlife: Habitat, Natural History and Distribution. General Technical Report NE 108, Broomall PA: U. S. Dept. of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station.

The rock shrew (also known as the long-tailed shrew) is a small, dull gray-black shrew with nearly uniform coloration in all seasons. The tail is indistinctly bicolored; black above, usually paler below; and is long, sparsely haired, and rather heavy and ropelike in appearance. The long tail is this shrew’s trademark. The body of the rock shrew is slender, and the snout is long, slender, highly movable, and incessantly rotating, with conspicuous vibrissae. The eyes are minute but visible, and the ears usually project slightly above the pelage (fur). The skull is long, narrow, and depressed. The two sexes are equal in size. Measurements of overall length range from 10-14 cm (~4 - 5.5 in); tail lengths range from 5-6 cm (2.0-2.3 in); and hind foot length is 12-15 mm (0.47-0.59 in). Weights vary from 4-6 g (0.14-0.21 oz).

Similar species: The masked shrew (Sorex cinereus), smoky shrew (Sorex fumeus), and water shrew (Sorex palustris, a species of Special Concern in Massachusetts) are the three species of shrews in the state that most closely resemble the rock shrew. The masked shrew is the most common long-tailed shrew with a range overlapping that of the rock shrew, but it is generally smaller and is brown rather than gray in color. The smoky shrew is more likely to be confused with the rock shrew, particularly in winter when both are the same shade of dark gray. At that time of year, they can be distinguished by looking at the belly hair. The belly hair of the smoky shrew turns a dull brownish gray, which differs markedly from the rock shrew’s intense gray-black fur. The smoky shrew is larger and more robust with a shorter and thinner tail, and noticeably larger front teeth than rock shrews. The water shrew is much larger and has a stiff fringe of hairs on the outer edges of its hind feet.

Life cycle and behavior

Little is known about this species beyond its appearance and the type of habitat it is most likely to be found in. It is believed that the rock shrew’s habits are much the same as those of the masked shrew or smoky shrew, which are often found in the same habitat. Fragments of spiders and centipedes as well as traces of plant material have been identified from stomach analysis, but the rock shrew probably kills and eats a great variety of insects and other small invertebrates. The rock shrew is appropriately named in that it forages in deep, subterranean tunnel systems among rocky outcrops, where there is little or no soil but rather a loose accumulation of boulders. This long-tailed shrew is well adapted for its life in rocky talus. Its long, slender body permits fine-tuned navigation of its labyrinth-like home, its long tail facilitates balancing while climbing, and its flattened skull with a narrow rostrum and protruding incisors act like forceps to pick small invertebrates out of tight places.

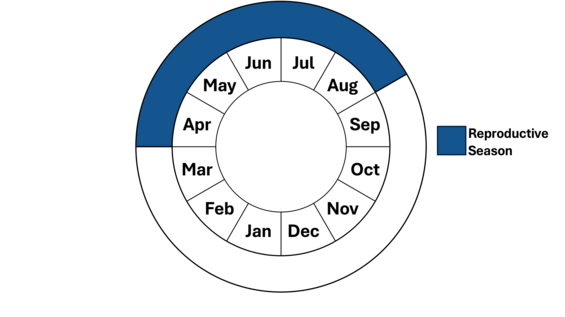

Because it is difficult to capture the rock shrew within its home of boulders, very little is known about its breeding behavior. Breeding activity is believed to begin in early spring and continue until the end of summer. The gestation period is unknown. Probably multiple litters of 2 to 5 offspring are produced yearly.

Population status

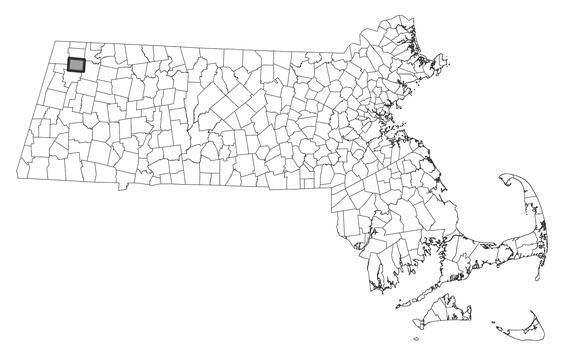

The rock shrew is currently listed under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act as a species of Special Concern in Massachusetts. In Massachusetts, the rock shrew has only been cited Berkshire County. As of 2025, only 9 specimens have been documented in 4 of the 351 municipalities, but this shrew is probably much more common and secure in its limited habitat than these few records would suggest.

Distribution and abundance

Sorex dispar, meaning “different shrew,” is restricted to rocky mountain habitats in or near the Appalachian Mountains. The range of the rock shrew extends from isolated high elevations in the mountains of North Carolina and Tennessee, north through central Pennsylvania, western New Jersey, eastern New York, western Massachusetts, and Maine to the tip of the Gaspe Peninsula of Quebec, and into Cape Breton, Nova Scotia. In Massachusetts, this shrew is known from only one historic and two current sites in Berkshire County, but probably occurs in other places in the mountains of northern Berkshire County.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

2000-2025

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

The rock shrew prefers cold, deep, damp forests, particularly old-growth forests with hemlock or spruce. It is primarily a shrew of wooded rockslides or talus, just beneath low, shaded cliffs, and at the edges of nearby mountain streams. It can also be found in depressions of moist moss-covered logs and in crevices of large mossy rock piles. Occasionally, the rock shrew occurs in much drier spots but is almost invariably associated with rock crevices and rockslides.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

At present, there appears to be no immediate threat to the habitat of the rock shrew.

Conservation

Specific management recommendations are to protect streams and moist rocky hillsides at higher elevations.

References

Godin, A.J. 1977. Wild Mammals of New England. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins Press.

Kirkland, G.L. Jr. 1981. Sorex dispar and Sorex gaspensis. Mammalian Species 155:1-4.

Laerm, J. and W.M. Ford. 2007. Long-tailed shrew, Sorex dispar (Batchelder, 1911). Pp. 91-94. In M.K. Trani, W.M. Ford, B.R. Chapman (eds.) The Land Manager’s Guide to Mammals of the South. TNC and U.S. Forest Service. 546 p.

Merritt, J.F. 1987. Guide to the Mammals of Pennsylvania. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: University of Pittsburg Press.

Contact

| Date published: | March 5, 2025 |

|---|