- Scientific name: Sterna dougallii

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

- Endangered (US Endangered Species Act)

Description

Roseate tern (Sterna dougallii)

The roseate tern measures 33-41 cm (13-16 in) in length and weighs 95-130 g (3.4-4.6 oz). Breeding adults have pale gray upperparts, white underparts (flushed with pale pink early in the breeding season), a black cap, orange legs and feet, and a black bill (which becomes red at the base as the season progresses). The tail is mostly white and deeply forked with two very long outer streamers that extend well past the tips of the folded wings. In non-breeding adults, the forehead becomes white and the crown becomes white marked with black, merging with a black patch that extends from the eyes back to the nape. The down of hatchlings is distinctive: it is grizzled buff/black or gray/black and spiky-looking because the filaments are gathered at the tips. Juveniles are buff or gray above, barred with black chevrons, and have a mottled forehead and crown, black eye-to-nape patch, and black bill and legs. The roseate’s vocal array includes a high-pitched chi-vik advertising call, and musical kliu and raspy aaach alarm calls, the latter sometimes likened to the sound of tearing cloth.

Life cycle and behavior

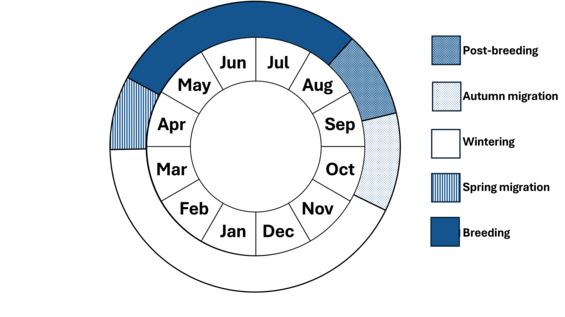

Roseates usually begin to arrive in Massachusetts in mid/late-April or the first week of May. They begin to alight on the nesting beaches shortly thereafter, spending progressively more time on land engaged in territoriality and courtship as the egg-laying period nears. Egg dates are May 9th-August 18th. Laying usually begins about 5-8 days later than that of Common terns in the same colony. Incubation lasts about 3 weeks, and the hatchling period about 4 weeks. Massachusetts birds depart from breeding colonies about 5-15 days after fledging in July and August (peak: mid-July to early August) and concentrate for several weeks in pre-migratory staging areas around Cape Cod and the islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket before departure for wintering grounds in August and September.

Figure 1. Phenology in Massachusetts. This is a simplification of the annual life cycle. Timing exhibited by individuals in a population varies, so adjacent life stages generally overlap each other at their starts and ends.

Colony. The roseate tern is gregarious. In the northeast it nests in colonies of a few to about 2,400 pairs, the size of the largest colony in Massachusetts. In this portion of its range, the roseate invariably nests with the common tern, often in clusters within the larger common tern colony. Pairs are territorial and defend their nest sites.

Responses to predators and intruders. The roseate tern prefers to nest on islands lacking mammalian predators. Eggs and chicks are cryptically colored and well-concealed under vegetation, debris, or rocks. Colony-nesting seabirds, such as terns, benefit from group defense. Roseates are less aggressive than common terns and rely on them for defense in the colony. Attack rate peaks at hatching. Roseates dive at, and sometimes strike, various avian predators. Roseates circle above and dive at humans but generally do not make physical contact or defecate on them. Roseates in the Caribbean have been shown to respond more vigorously to familiar versus unfamiliar humans. As is the case for common terns, roseates desert colonies at night when subject to nocturnal predation, prolonging incubation of eggs and exposing eggs and chicks to the elements and predation. Roseate nests and chicks, however, are better concealed, and thus less vulnerable, than those of common terns. Roseate adults, in contrast, are often disproportionately preyed upon in comparison to common terns from the same colony. Perhaps for this reason roseates are quicker to abandon a site when predators are active.

Pair-bond and parental care. Courtship involves both aerial and ground displays, including spectacular high flights (in which ≥ 2 birds spiral up to 30-300 m [33-328 yards] above ground and then descend in a zig-zag glide) and low flights (in which a fish-carrying male is chased by up to 12 other birds). Males feed females before and during the egg-laying period. The roseate tern is socially monogamous, but extra-pair copulations occur. Both parents spend roughly equal amounts of time incubating, and incubation shifts last about 26 minutes. Males and females also contribute approximately equally to brooding and feeding chicks. Older adults are more productive than younger ones. Pair bonds typically last about two years but pair bonds of up to 12 years have been documented. The sex ratio is skewed towards females (1.27 females:1 male) in Massachusetts and perhaps the entire northeast population. This results in multi-female associations (≥ 2 females) in which females together care for eggs and young that may result from copulations with males that are attending nests elsewhere in the colony.

Nests. Nests (usually beneath or immediately alongside vegetation, boulders, or debris, or in nest boxes) are depressions or “scrapes” in the substrate, to which nesting material may or may not be added throughout incubation. In the northeast, nests are usually 50-250 cm apart, depending on the distribution of vegetation and rocks. Only one brood per season is raised, but birds may renest after losing eggs or young chicks.

Eggs. Eggs are various shades of cream or brown with dark spots and streaks. Eggs are sub-elliptical in shape and measure approximately 43 mm x 30 mm (1.7 x 1.2 in). Roseate tern eggs are difficult to distinguish from common tern eggs: roseate eggs are generally longer, more conical (less rounded), more uniformly and finely spotted, and have greater contrast between a paler background and darker spots. Clutch size is usually 1-2 eggs; older females generally lay 2 eggs (laid about 3 days apart), and younger females, 1 egg. Nests with 3 or more eggs are often attended by more than one female. Incubation, which begins after laying of the first egg, may be sporadic until the second egg is laid. The period between laying and hatching is about 23 days for both eggs.

Young. Chicks are semi-precocial. They are downy at hatching, their eyes open after a couple hours, and they can waddle and take food within hours of hatching. In 2-chick broods, there is often a substantial size difference between siblings that persists throughout the growth period because the first chick (A-chick) is usually 3 days older. Chicks are brooded/attended most of the day and night for the first few days of life. Parental attendance ceases after about a week, except for cold, rainy days. Parents carry prey to chicks in their bills one fish at a time at an average rate of 1 fish/hour. At sheltered nests, undisturbed chicks may remain at the nest site until they are nearly fledged. Where there is more disturbance, chicks may move away to new hiding spots. Estimating survival is challenging due to inaccessible nest sites and chicks’ hiding behavior. In 2-chick broods, the younger chick (B-chick) is less likely to survive than the A-chick. Most losses of B-chicks are due to starvation. The peak of fledging is at 27-30 days. Three to seven days after fledging, young birds accompany parents to fishing grounds. They begin to catch fish about 15 days after fledging but remain dependent on parents for food at least until migration. This notably long period of dependence reflects the highly specialized fishing techniques that the young must master. At Bird Island, MA, family units depart the nesting colony 5-15 days post-fledging to congregate at staging locations. When two chicks are raised, the male leaves first with the older chick and the female leaves up to 7 days later with the younger chick. Nothing is known of family cohesion during migration.

Diet and foraging: The roseate tern feeds almost exclusively on small fish; occasionally it includes crustaceans in its diet. It is fairly specialized: sand lance typically dominates the diet in the northeast. Other prey species of importance in Massachusetts are herrings, bluefish, mackerel, silversides, and anchovies. In the northeast, it often forages with common terns. The roseate captures food mainly by plunge-diving (diving from heights of 1-12 m (3-40 ft) and often submerging to 50 cm [~1.5 ft]), but also by surface-dipping and contact-dipping. Some individuals specialize in stealing fish from common terns.

Demography and survival: Most roseate terns start breeding at 3-4 years old. Birds in the northeast are thought to breed annually but may skip breeding when prey availability is low. Productivity, usually in the range of 0.9-1.4 fledglings/pair in the northeast, declines as laying date increases. Annual survival of adults in the northeast was estimated to be about 83.5%. The oldest documented wild roseate tern was a Massachusetts-hatched bird encountered alive at 28 years and 1 month old.

Population status

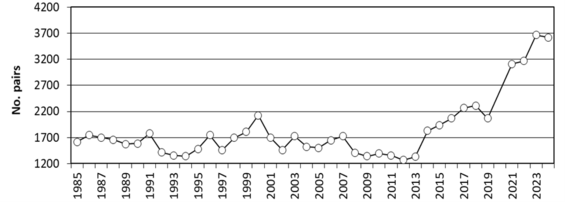

The northeast population of the roseate tern is listed as Endangered federally and in Massachusetts principally because of its range contraction and secondarily because of its declining numbers. Prior to 1870, its status was somewhat obscure, but the roseate was considered to be an abundant breeder within common tern colonies on Nantucket and Muskeget Islands, MA. Prior to the 20th century, egging was a problem in northeast colonies, but it was persecution of terns for the plume industry that greatly reduced numbers in the northeast to perhaps 2,000 pairs, mostly at Muskeget and Penikese Islands, MA, by the 1880s. Following protection, numbers rose to the 8,500 pair level in 1930. From the 1930s through the 1970s, roseates were displaced from breeding colonies by nesting herring and great black-backed gulls and had declined to 2,500 pairs by 1979. Following two decades of fairly steady increase, the northeast U.S. population peaked at 4,310 pairs in 2000. It subsequently declined rapidly for unknown reasons to pre-listing levels (about 3,000 pairs) through 2013 (USFWS, unpubl. data). In 2014, the population started recovering. As of 2024, it numbered approximately 6,200 pairs (USFWS, unpubl. data). The restoration of nesting habitat at Bird Island, Marion, MA, completed in 2018, helped to drive this increase. As of 2024, over 90% of the northeast U.S. population continues to be dangerously concentrated at just 3 colonies: Bird Island, Marion, MA (2,400 pairs); Great Gull Island, NY (2,200 pairs); and Ram I., Mattapoisett, MA (1,200 pairs). Massachusetts’ population numbered approximately 3,700 pairs in 2024 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Number of nesting roseate tern pairs in Massachusetts, 1985 – 2024.

Distribution and abundance

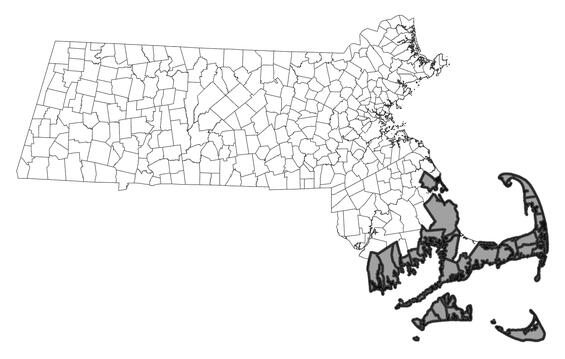

The roseate tern has a scattered breeding distribution primarily in the tropical and sub-tropical Atlantic, Indian, and Pacific Oceans. In North America, it breeds in two discrete populations: from Nova Scotia south to New York and in the Caribbean. The northeast population, at about 40-45° N, is among the most northernmost nesting groups of this mostly tropical species. Approximately 90% of the northeast population nests at just three sites: Bird and Ram Island in Buzzards Bay, Massachusetts, and Great Gull Island in NY. Roseates in Massachusetts nest at just a handful of locations annually, five sites in 2024. After the breeding season, Massachusetts birds move to pre-migratory staging areas around Cape Cod and the islands of Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket before departure for wintering grounds. Roseates feed offshore and return to the staging areas to rest and roost. Most have departed staging areas and have begun migrating southward by mid- to late-September. Along the way, they rest on the water and along Caribbean and South American shorelines before reaching their final destinations. With advances in tracking technology, migratory staging and wintering areas for this population have become better understood in recent years. northeastern birds winter along the north and east coasts of South America southward along the coast of Brazil to approximately 21° S. However, much more information about distribution and ecology on the migratory staging and wintering grounds remains to be discovered.

Distribution in Massachusetts. 1999-2024. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

In Massachusetts, the roseate tern generally nests on sandy, gravelly, or rocky islands and, less commonly, in small numbers at the ends of long barrier beaches. Compared to the common tern, it selects nest sites with denser vegetation, such as seaside goldenrod and beach pea, and rockier substrate, which provide excellent cover for chicks. It feeds in highly specialized situations over shallow sandbars, shoals, inlets, schools of predatory fish, or flocks of foraging double-crested cormorants, which drive smaller prey to the surface. The roseate is known to forage up to 48 km (30 mi) from the breeding colony. Post-breeding staging areas are typically tidal flats, sandbars, or low-lying barrier island beaches. Outside of the breeding season, they may forage in association with tunas many miles offshore.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Roseate tern (Sterna dougallii)

Threats

Loss of colony sites: Desertion of ≥ 30 major breeding sites over the past 80 years in most cases has been related to occupation of sites by gulls, and secondarily, to predation in the colonies; the latter may have intensified as terns were displaced by gulls to sites closer to the mainland.

Habitat loss: Nesting and staging habitat is threatened by overwash and erosion of low-lying areas, rising sea levels, and increasing frequency and intensity of storms due to climate change. Proliferation of invasive vegetation degrades nesting habitat. High human disturbance is a feature of many northeast staging sites, causing repeated flushing of flocks with probable separations of parents and still-dependent young, and some more accessible breeding sites.

Predators. In North America, predators of roseate tern eggs, young, and adults include birds and mammals, snakes, ants, and land crabs. In the northeast, significant predators on adults, eggs, or chicks include: herring and great black-backed gulls, black-crowned night-heron, great horned owl, peregrine falcon, American crow, American mink, and red fox. Many other predators causing significant impacts have been documented.

Climate change: In addition to climate-induced habitat loss from rising sea levels and storms, the rapid warming of the northwest Atlantic Ocean threatens the prey base of this specialized feeder through changes in prey distribution, abundance, and/or phenology. The roseate tern, like many seabirds, does not appear to be shifting the timing of breeding in response to warming seas.

Contaminants: Contaminants have had negative impacts on roseate terns. Locally, they were impacted by the release of PCBs into the New Bedford Harbor area from the 1940s through the 1970s; they were exposed to toxic levels of PCBs and possibly DDE. The 2003 Bouchard 120 oil spill in Buzzards Bay had negative impacts on roseate terns and degraded their nesting habitat.

Wind farms: The construction and operation of offshore wind turbines, which are poised to proliferate in the northeast, may cause changes to prey availability, displacement from foraging habitat, and mortality from collisions.

Disease and biological toxins: To date, diseases have not had a major impact on roseate terns in Massachusetts. However, diseases, including emerging ones such as HPAI, potentially could have large impacts in the future. On at least one occasion, Paralytic Shellfish Poisoning (“red tide”) has caused mortality of large numbers of roseates in Massachusetts.

Wintering grounds: Knowledge of threats on the wintering grounds is substantially incomplete. The species is less protected outside of the breeding area. Persecution by humans on the wintering grounds has been documented, but the extent to which this occurs is unknown. In recent years, substantial numbers of roseate and Common terns have been killed by coastal powerlines in Brazil and international cooperative efforts are underway to mitigate this loss. Development of coastal habitat for tourism infrastructure is an ongoing threat.

Plastics: Plastic trash in the environment poses a threat as it can be mistaken as food by seabirds and shorebirds and ingested or cause entanglement. Ingested plastics, common for seabirds, can block digestive tracts, cause internal injuries, disrupt the endocrine system, and lead to death. Entanglement from fishing gear and other string-like plastics can cause mortality by strangulation and impairing movements.

Roseate tern (Sterna dougallii)

Conservation

The roseate tern is a conservation-dependent species. The loss of breeding sites in the northeast, coupled with the roseate’s reluctance to colonize new sites, is a serious obstacle to recovery of the northeast population. Nearly all the roseates in Massachusetts and over half of the northeast population are concentrated at Bird and Ram Island in Buzzards Bay, despite apparently suitable conditions elsewhere, presenting a substantial risk to the population should one of these sites become unsuitable. Similarly, the dependence of the northeast population on a limited number of post-breeding staging sites in and around Cape Cod elevates Massachusetts’s responsibility for protection during this critical part of the life cycle.

Nesting: Tern protection and restoration are ongoing, long-term commitments that require regular management and monitoring to track progress, identify threats, control vegetation, prevent gulls from encroaching on colonies, and remove predators. Annually, colonies are protected by posting of signs, presence of wardens, and/or exclusion of visitors and their pets. Wooden nest boxes, boards, and other structures may enhance the number of potential nest sites. Vegetation control is sometimes necessary when it is dense enough to impede adults’ ability to access nesting sites or feed young, or when it degrades habitat.

Because of the regional importance of Massachusetts for roseate recovery, several restoration projects have been initiated in the state. Restoring common terns to nesting sites is a necessary first step in restoring roseates because of this species’ close association with the common tern at breeding colonies. The stabilization and nourishment of Bird Island, MA in 2015-2018 doubled the amount of roseate and common tern nesting habitat and resulted in major increases of both species at the site. Roseate and common terns were successfully restored to Ram Island after a gull control program in 1990-1991; a nourishment project in 2010-2011 countered erosion of nesting habitat; and as of 2025, a major habitat restoration project is in the design phase. A restoration program at Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge, begun in 1996, encouraged the expansion of a huge colony of common terns (about 20,000 pairs in 2024). While only a small number of roseates typically nest there, it is one of the region’s most important staging sites, supporting roseates from colonies throughout the northeast population. A project at Penikese Island in Buzzards Bay that began in 1998, involves discouragement of gulls from small portions of the island and managing predators and vegetation; roseates returned to Penikese in 2003, but numbers fluctuate widely from year to year.

Staging: Protecting flocks from disturbance by people and their pets is necessary to allow terns to rest and feed to prepare for migration.

Wintering: Much more information about distribution, ecology, and threats on the wintering grounds is needed to facilitate conservation. International cooperation is and will continue to be essential to protection of this species, which spends half of the year outside of North America.

Avoid or recycle single-use plastics and promote and participate in beach cleanup efforts.

Acknowledgments

Beach-nesting birds in Massachusetts are protected and managed by an extensive network of highly dedicated and conservation-minded landowners, individuals, organizations, and agencies. The birds’ successes are their successes.

References

Althouse, M. A., J. B. Cohen, S. M. Karpanty, J. A. Spendelow, K. L. Davis, K. C. Parsons and C. F. Luttazi. 2019. Evaluating response distances to develop buffer zones for staging terns. Journal of Wildlife Management 83(2):260–271.

Bird Banding Laboratory. North American Bird Banding Program Longevity Records. Version 2023.2. Eastern Ecological Science Center. US Geological Survey. Laurel, MD.

Blodget, B.G., and S.M. Melvin. Massachusetts tern and Piping Plover Handbook: A Manual for Stewards. Westborough, MA: Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, 1996.

Davis, K. L., S. M. Karpanty, J. A. Spendelow, J. B. Cohen, M. A. Althouse, K. C. Parsons, C. F. Luttazi, D. H. Catlin, and D. Gibson. 2019. Residency, recruitment, and stopover duration of hatch year roseate terns (Sterna dougallii) during the premigratory staging period. Avian Conservation and Ecology 14(2):11.

Gochfeld, M. and J. Burger (2020). Roseate tern (Sterna dougallii), version 1.0. In Birds of the World (S. M. Billerman, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA.

Loring P.H., T.M. Kuras, R.A. Revorêdo, D.S.D. Farias, F.J.L. Silva, P.C. Lima, S. von Oettingen, J. Walsh. 2023. Habitat use of Common and roseate terns tracked with satellite transmitters in northeast Brazil. U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. State of the Birds Program. 38 pp.

Loring P. H., P. W. Paton, J. D. McLaren, H. Bai, R. Janaswamy, H. F. Goyert, C. R. Griffin, and P. R. Sievert. 2019. Tracking Offshore Occurrence of Common terns, Endangered roseate terns, and Threatened Piping Plovers with VHF Arrays. Sterling (VA): US Department of the Interior, Bureau of Ocean Energy Management. OCS Study BOEM 2019-017.

Keogan, K., Daunt, F., Wanless, S., Phillips, R. A., Walling, C. A., Agnew, P., … Lewis, S. 2018. Global phenological insensitivity to shifting ocean temperatures among seabirds. Nature Climate Change 8: 313 – 318. https://doi.org/10.1038/s4155 8-018-0115-z.

Mostello, C. S., I.C. T. Nisbet, S. A. Oswald, J. W. Fox. 2014. Non-breeding season movements of six North American roseate terns Sterna dougallii tracked with geolocators. Seabird, 40 27. 1-21.

Nacci, D. E., M. E. Hahn, S. I. Karchner, S. Jayaraman, C. S. Mostello, K. M. Miller, C. Gilchrist Blackwell, and I. C. T. Nisbet. 2016. Integrating monitoring and genetic methods to infer historical risks of PCBs and DDE to common and roseate terns nesting near the New Bedford Harbor Superfund Site (Massachusetts, USA). Environ. Sci. Technol. 50 (18): 10226-10235.

Nisbet, I. C. T., M. Gochfeld, and J. Burger (2014). Roseate tern (Sterna dougallii), version 2.0. In The Birds of North America (A. F. Poole, Editor). Cornell Lab of Ornithology, Ithaca, NY, USA. https://doi.org/10.2173/bna.370

Nisbet, I. C. T. & Mostello, C. S. 2015. Winter quarters and migration routes of common and roseate terns revealed by tracking with geolocators. Bird Observer 43: 222-231.

Oswald, S.A., Nisbet, I. C. T., & Mostello, C. S. 2023. Common terns Sterna hirundo and roseate terns Sterna dougallii frequently rest on the sea surface in winter quarters and during migration, Bird Study, DOI: 10.1080/00063657.2023.2237232

Paton, P. W. C., P.H. Loring, G.D. Cormons, K.D. Meyer, S. Williams, and L.J. Welch. 2020. Fate of Common (Sterna hirundo) and roseate terns (S. dougallii) with Satellite Transmitters Attached with Backpack Harnesses. Waterbirds 43(3-4), 342-347

Spendelow, J. A., J. E. Hines, J. D. Nichols, I. C. T. Nisbet, G. Cormons, H. Hays, J. J. Hatch, and C. S. Mostello. 2008. Temporal variation in adult survival rates of roseate terns during periods of increasing and declining populations. Waterbirds 31(3): 309-319.

Staudinger, M. D., H. Goyert, J. Suca, K. Coleman, L. Welch, J. Llopiz, I. Altman, D. Wiley, A. Appelgate, P. Auster, H. Baumann, J. Beaty, D. Boelke, L. Kaufman, P. Loring, J. Moxley, S. Paton, K. Powers, D. Richardson, J. Robbins, J. Runge, B. Smith, C. Spiegel, H. Steinmetz. 2020. The role of sand lances (Ammodytes sp.) in the Northwest Atlantic Ecosystem: A synthesis of current knowledge with implications for conservation and management. Fish and Fisheries 21 (3):522–556. https://doi.org/10.1111/faf.12445

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Roseate tern Recovery Plan: Northeastern Population. First update. Hadley, MA: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, 1998.

U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. (Accessed 2/24/25) International partners respond to roseate tern deaths in Brazil. https://www.fws.gov/story/teaming-terns

Veit, R.R., and W.R. Petersen. Birds of Massachusetts. Lincoln, MA: Massachusetts Audubon Society, 1993.

Yakola, K.C. 2019. An examination of tern diets in a changing Gulf of Maine. Master Thesis, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, MA.

Contact

| Date published: | April 23, 2025 |

|---|