- Scientific name: Enallagma pictum

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Threatened (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Male scarlet bluet

The scarlet bluet is a small, semi-aquatic insect of the order Odonata, suborder Zygoptera (the damselflies), and family Coenagrionidae (pond damsels). Like most damselflies, scarlet bluets have large eyes on the sides of the head, short antennae, and four heavily veined wings that are held folded together over the back. The eyes are red with a small red spot behind each eye on the back of the head, which is black. The spots are connected by a thin red bar. The scarlet bluet has a long, slender abdomen, composed of ten segments. The abdominal segments are orange below and black above. The male’s thorax (winged and legged section behind the head) is red with black stripes on the “shoulders” and top. Females are similar in appearance but have a duller yellow thorax and thicker abdomens than the males. Scarlet bluets average 26-29 mm (just over one inch) in length.

The bluets (genus Enallagma) comprise a large group of damselflies, with more than 20 species in Massachusetts. However, this is the only red bluet in the Northeast; most bluets are blue, except for one yellow, one orange, and one red species. The eastern red damsel (Amphiagrion saucium) is also red, but is smaller, and the abdomen is entirely red, unlike the scarlet bluet, whose abdomen is black above and orange below. The orange bluet (E. signatum) is also similar, but not as red, and the second to last abdominal segment is entirely orange, unlike the scarlet bluet, which is black above and orange below. The vesper bluet (E. vesperum) bears some resemblance but is more yellow overall and the tip of the abdomen is blue.

Life cycle and behavior

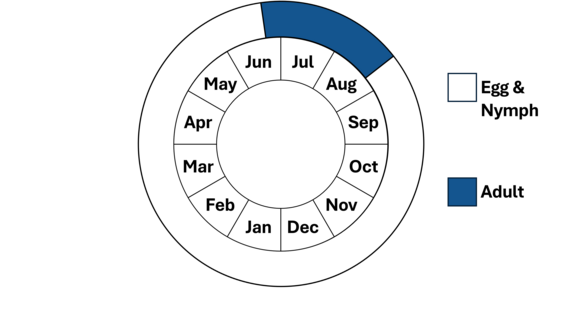

Note adult life stage is synonymous with fight period.

Although little has been published on the life history of the scarlet bluet, it is likely similar to other, better-studied species in the genus. All odonates have three life stages: the egg, the aquatic nymph, and flying adult. The nymphs are slender with three leaf-like appendages extending from the end of the body which serve as breathing gills. They have a large, hinged lower jaw which they can extend forward with lightning speed. This feature is used to catch prey, the nymph typically lying in wait until potential prey passes within striking range. They feed on a wide variety of aquatic life, including insects and worms. They spend most of their time clinging to submerged vegetation or other objects, moving infrequently. They transport themselves primarily by walking, but are also capable of swimming with a sinuous, snake-like motion.

Scarlet bluets have a one-year life cycle. The eggs are laid during the summer and probably hatch in the fall. The nymphs develop over the winter and spring, undergoing several molts. In early to mid-summer the nymphs crawl up on emergent vegetation and begin their transformation into adults.

This process, known as emergence, typically takes a couple of hours, after which the newly emerged adults (tenerals) fly weakly off to upland areas where they spend a week or two feeding and maturing. The young adults are very susceptible to predators, particularly ants and spiders during emergence, and birds during the teneral stage. Mortality is high during these periods. The adults feed on a wide variety of smaller insects.

When mature, adults return to the wetlands. When a male locates a female, he attempts to grasp her behind the head with the terminal appendages at the end of his abdomen. If the female is receptive, she allows the male to grasp her, then curls the end of her abdomen up to the base of the male’s abdomen where his secondary sexual organs (“hamules”) are located. This coupling results in the heart-shaped tandem formation characteristic of all odonates. This coupling lasts for a few minutes to an hour or more. The pair generally remains stationary during this mating but, amazingly, can fly, albeit weakly, while coupled.

Once mating is complete, the female begins laying eggs (ovipositing) in aquatic vegetation, including the underside of lily pads, using the ovipositor on the underside of her abdomen to slice into the vegetation and deposit eggs. Although the female occasionally oviposits alone, in most cases the male remains attached to the back of the female’s head. This form of mate-guarding is thought to prevent other males from mating with the female before she completes egg-laying. The adult’s activities are almost exclusively limited to feeding and reproduction, and their life is short, probably averaging only three to four weeks for damselflies like the scarlet bluet. The flight season of the scarlet bluet lasts from late June through August with most occurrences in July.

Distribution and abundance

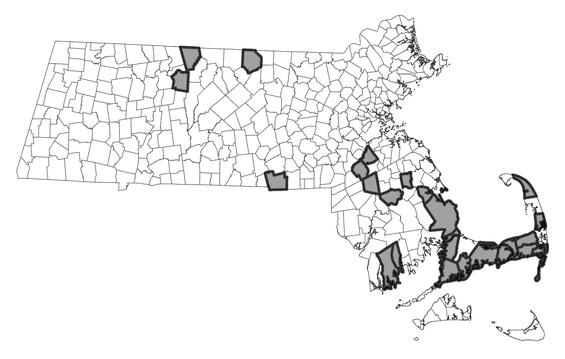

The scarlet bluet is a regional endemic and has a very restricted to scattered locations in the northeastern United States from New Jersey to southern Maine and into southwestern New Brunswick. In Massachusetts, scarlet bluet occurs in the Millers, Nashua, Blackstone, Neponset, Taunton, and Cape Cod watersheds, with most occurrences in southeast. Across a portion of its range, the species has undergone an apparent north and west range expansion in the past twenty years expanding from the coastal plain of southern New England and New York, into southern Maine, New Brunswick, and most of New Hampshire (Hunt 2012, McAlpine et al. 2017, Butler et al. 2019). Recent observations in Massachusetts have documented several new occurrences in sandy vegetated ponds in the Millers and Nashua River watersheds; however, it’s uncertain if these occurrences represent a range expansion in Massachusetts or limited survey effort. Further, recent effort failed to detect scarlet bluet at several ponds, despite apparent suitable habitat in the southeast, indicating potential population or subpopulation losses (Nikula 2019). Scarlet bluet is typically observed in low abundances, however large numbers have been observed.

The scarlet bluet is listed as a Threatened species in Massachusetts and is protected under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act (MG.L. c.131A) and its implementing regulations (321 CMR 10.00). As with all species listed in Massachusetts, individuals of the species are protected from take (picking, collecting, killing, etc.) and sale under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Scarlet bluets inhabit acidic, sandy ponds (including coastal plain ponds) with abundant floating vegetation, such as Nymphaea, Nuphar, and Brasenia (Gibbons et al. 2002, Butler and deMaynadier 2008, Hunt et al. 2020). Lentic systems include coastal plain ponds and impoundments with high shoreline and littoral habitat integrity (i.e., limited shoreline development; Butler and deMaynadier 2008, Hunt 2020). Nymphs are aquatic and inhabit aquatic vegetation beds. Adults spend much of their time flying out over the water, alighting on lily pads. Before they are sexually mature, the adults inhabit nearby forested uplands (Hunt 2020).

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Coastal plain pond habitat with an abundance of floating-leaved vegetation including Nymphaea.

Threats

The major threats to scarlet bluet are shoreline and wetland degradation and loss. Shoreline development may eliminate nearshore/littoral zone and riparian vegetation and harden shorelines through construction of buildings, roads, and other human constructions. Further, shoreline development facilitates increased nutrient and contaminant inputs (e.g., road salts, septic, fertilizer), sedimentation, surface and groundwater withdrawals or water level alteration (e.g., winter drawdown), pesticide use, introduction and spread of invasive species (aquatic vegetation and animals), and recreational activity (e.g., off-road vehicles, boat wakes). These activities lead to wetland/pond degradation that accelerates eutrophication, degrades water quality, and alters or eliminates aquatic vegetation composition required for scarlet bluet including floating-leaved vegetation. Invasive species including Phragmites can replace native vegetation creating unsuitable habitat conditions for scarlet bluet. In addition, climate change may create unfavorable conditions, including prolonged drought and high-water events, that in combination with ongoing habitat degradation (water withdrawals, nutrient inputs) can increase cyanobacteria blooms, reduce habitat, and alter aquatic vegetation composition unsuitable for the species. Since this species occasionally occupies impoundments, unmanaged dam removals may locally extirpate the species from sudden dewatering and habitat loss. High-impact recreational use, such as off-road vehicles driving through pond shores which may destroy breeding and nymphal habitat and motorboats whose wakes swamp delicate emerging adults, are also threats. Since scarlet bluets, spend a period of several days or more away from the pond maturing, it is important to maintain natural upland habitats adjoining the breeding sites for roosting and hunting. Without protected uplands the delicate newly emerged adults are more susceptible to predation and mortality from inclement weather (Hunt et al. 2020).

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

Standardized surveys should target known sites and new wetlands to determine scarlet bluet occupancy and population status. Surveys for adults are likely to be more effective for detection compared to nymph or exuvia as this life stage is extremely difficult to find and identify. Adult surveys should target nearshore, open-water, and riparian habitats during their flight period during standardized weather and time windows to maximize species detection. Multiple site visits (e.g., ≥3) are likely required to detect this species because of its typical low abundances and ephemerality. Known sites with breeding evidence should be monitored every 5 years or as needed (i.e., in response to extreme conditions like drought) to document changes in occupancy and habitat conditions. Effort should also be devoted to surveys at potential suitable sites to document potential range expansion (e.g., western MA) and update the species distribution and status in the state.

Management

Protection and restoration of shoreline/littoral zone, riparian, and upland habitat is critical for scarlet bluet persistence in Massachusetts. Actions that can improve or prevent habitat degradation include: reduction of nutrient, agricultural and road runoff; minimization of water level alteration that impacts native aquatic vegetation; minimization of groundwater withdrawals particularly during drought periods; prevention and management of nonnative aquatic vegetation; development of best practices for herbicide use; limitation and enforcement of off-road vehicles on shoreline habitat; management of dam removals to mitigate for potential habitat and population loss; and connection between ponds and other pond complexes.

Research needs

Research effort is needed to estimate detection and occupancy rates and how other environmental variables (e.g., sample timing, weather) affect these rates. Identification of source and sink wetland sites and general population dynamics within and across pond complexes is needed in Massachusetts to prioritize site conservation. Other needed research efforts include estimation of physiological tolerances to insecticides and herbicides; impacts of non-native fish and aquatic vegetation on populations; and projections of species distribution under climate change scenarios and climate vulnerability analysis.

References

Brown, V.A. 2020. Dragonflies and Damselflies of Rhode Island. Rhode Island Division of Fish and Wildlife, Department of Environmental Management, West Kingston RI.

Butler, R.G., H. Mealey, E. Kelly, A. St. Pierre, L. Wadleigh, and P.G. deMaynadier. 2019. Status, Distribution, and Conservation Planning for Endemic Damselflies of the Northeast: Maine. Report to Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife. University of Maine, Farmington.

Gibbons, L.K., J.M. Reed, and F.S. Chew. 2002. Habitat requirements and local persistence of three damselfly species (odonata: coenagrionidae). Journal of Insect Conservation 6:47-55.

Hunt, P.D. 2012. The New Hampshire Dragonfly Survey: A Final Report. Report to the New Hampshire Fish and Game Department, New Hampshire Audubon, Concord.

Hunt, P. 2020. Conservation planning for endemic damselflies of the northeast: A report to the Sarah K. deCoizart Article TENTH Perpetual Charitable Trust. Concord, NH. 18 p.

Hunt, P., V. Brown, R. Butler, P. deMaynadier, L. Harper, L. Saucier, R. Somes, E. White. 2020. A conservation plan for the endemic damselflies of the northeast. 20 p.

Lam, E. 2004. Damselflies of the northeast. Biodiversity Books, Forest Hills, New York, 96 p.

McAlpine, D.F., H.S. Makepeace, D.L. Sabine, P.M. Brunelle, J. Bell, and G. Taylor. 2017. First occurrence of Enallagma pictum (scarlet bluet) (Ononata: Coenagrionidae) in Canada and additional records of Celithemis martha (Martha’s Pennant) (Odonata: Libellulidae) in New Brunswick: possible climate-change induced range extensions of Atlantic Coastal Plain Odonata. J. Acad. Entomol. Soc. 13: 49-53.

Nikula, B. 2019. A survey for five species of Enallagma (bluet) damselflies in southeastern Massachusetts. Report to Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program, Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, Westborough, MA.

Nikula, B., J.L. Ryan, and M.R. Burne. 2007. A Field Guide to the Dragonflies and Damselflies of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program.

Walker, E.M. 1953. The Odonata of Canada and Alaska, Vol. I. University of Toronto Press.

Westfall, M.J., Jr., and M.L. May. 1996. Damselflies of North America. Scientific Publishers.

Contact

| Date published: | April 7, 2025 |

|---|