Purpose of Study

The education of children in foster care and state care presents an extraordinary challenge to the school systems of Massachusetts. Students transitioned into foster care have been traumatized, taken from the homes they have known, and frequently moved during their time in the programs. To have any measure of academic success, these vulnerable children require high levels of educational and emotional support. Federal law and regulation, along with state law and regulation in the areas of both child welfare and K-12 education, provide a complicated context for the required academic and human services.

Educational success for this vulnerable population is guided by birth families, foster families, child welfare officials, state education administrators, and local school personnel. This report tries to make the narratives of these stakeholders as understandable as possible while not losing sight of the data and the underlying goals of the system: promoting the education and welfare of the child. The research from the Division of Local Mandates (DLM) has a unique perspective on this policy area through its charge to measure the impact of state law and policy on municipalities. The report results from discussions with a wide range of participants in this system. The report contains a series of findings and recommendations that shine a light on ideas and spark a conversation, leading to improvements for everyone involved in this system.

Fundamentally, the system is challenged by a series of disconnected parts:

- systemic communication and cooperation gaps between child welfare and local education staff,

- unclear direction from federal law that governs foster care and education responsibilities for the state and local schools,

- a shortage of resources to fund transportation requirements,

- increasing demand for services as the foster care population grows, and

- disproportionate impacts on resource-constrained communities.

This is not a new challenge. Starting in 1896, the Commonwealth of Massachusetts took steps to ensure that the educational needs of students in foster care were met by cities and towns. Section 7 of Chapter 76 of the Massachusetts General Laws provides a reimbursement mechanism to school districts that host students placed by the state in a district other than their district of origin.1 Section 11 of the same chapter spells out a commitment to provide funding to school districts for students in state custody that attend a school district other than their district of origin. These items are consistent with the constitutional and legal provisions of Section 1 of Chapter 69 of the General Laws, which states that “a paramount goal of the commonwealth [is] to provide a public education system of sufficient quality to extend to all children . . . the opportunity to reach their full potential and to lead lives as participants in the political and social life of the commonwealth and as contributors to its economy.” With this context as backdrop, the purposes of this study are to:

- identify those aspects of state law, regulation, and policy that pertain to the provision of educational services to students in foster care and state care;2

- make recommendations for changes designed to enhance the Commonwealth’s efforts to support and improve the availability, quality, and cost-effectiveness of elementary and secondary education for these vulnerable children; and

- examine the current cost impacts of relevant state law and policy on local school districts that serve students in state care and foster care.

Education of Children in Foster Care: An Introduction

The education of children in foster care is a subject governed by federal and state child welfare laws, as well as federal and state education laws. It is a service delivered at the intersection of numerous government agencies, including the US Department of Health and Human Services, the US Department of Education, the Massachusetts Department of Children and Families (DCF), the Massachusetts Department of Elementary and Secondary Education (DESE), and local school districts. The federal government provides states with overarching laws, regulations, and policies that govern the treatment of children in foster care. These federal requirements must be interpreted and implemented by the state of Massachusetts and by local school districts. Given the complexity and overlap of these rules, there is confusion about how Massachusetts and local school districts should implement federal policies such as school transportation and its funding. Additionally, because services to children in foster care are governed by numerous entities at the state and local levels—including DCF, DESE, and the school districts—there can be disconnects in how these government agencies interact with each other to fulfill the needs of these students. Some of these interactions relate to funding of services; some relate to the planning and delivery of the services themselves.

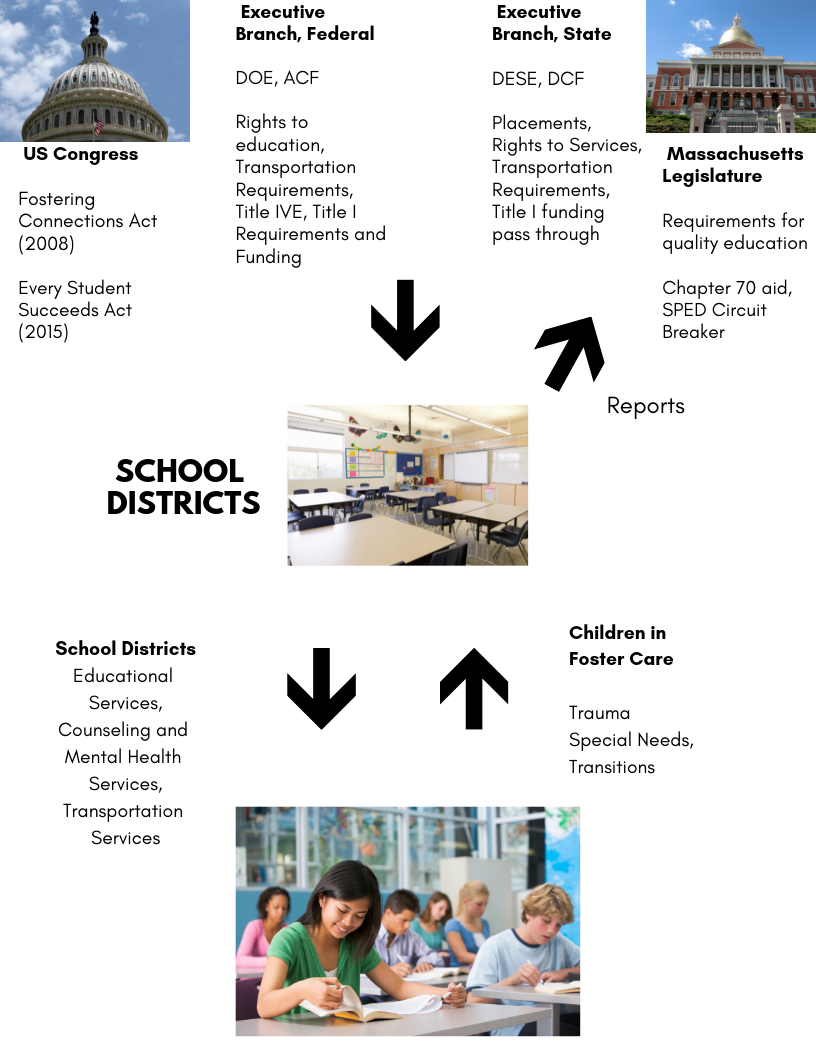

To break this subject into its components, this report includes diagrams to illustrate the obligations of the different government entities and the problems that arise in this system. In Figure 1, the discrete actors are arranged to show relationships of rights and responsibilities. The balance of this section will be organized to mirror those relationships. It will cover the challenges for students and their caregivers, the federal government’s role, the state government’s role, and the impact on school districts—including thoughts on mandates in this area of education policy.

Children in Foster Care

From the founding of Massachusetts, its people made a policy decision to provide all children in the Commonwealth with a free and quality public education to ensure that Massachusetts would have a well-educated citizenry.3 In addition to Massachusetts’ own constitutional and legal commitments to educating children, through the participation of Massachusetts in federal programs the state further bound itself to an appropriate level of educational services for various types of children and families that may have needs beyond those of the average student. In that context, the Commonwealth receives significant federal funding to support the foster care program, as well as grants for elementary and secondary education that require specific actions by the state and municipalities to maintain eligibility.

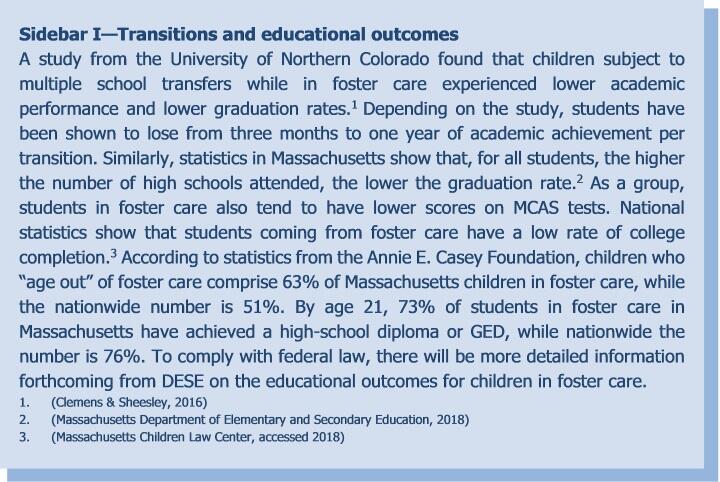

While educating children to become engaged citizens requires educators to provide a certain amount of care and resources, vulnerable student populations require special care and additional resources to achieve outcomes that could be described as successful. Vulnerable populations include students with special needs, English language learners, children from economically disadvantaged backgrounds, homeless students, children in foster care, and children with court involvements. Children in foster care have specific challenges that are recognized in law and regulation, which flow from a rich research history that catalogues the challenges faced by these students. Because of the high number of changes in placement, foster children experience a higher rate of school transfers, which researchers have demonstrated can have a negative effect on education outcomes.4 The evidence strongly suggests that, for these at-risk students, specific student-level and school-level interventions are required to compensate for the lack of consistency in curriculum (because of the changes in placements) and to boost achievement both in K-12 education and beyond. To provide the necessary support, school districts allocate additional resources to support the educational stability and success of these students. This is why federal law mandates that the default position is to keep the child in their school of origin (where they resided before their placement in foster care) absent a determination by relevant stakeholders that the child’s best interest is served by attending school in the district of foster care placement.

Data from DESE indicates that for a broad population of students in state care, defined as DCF involved and measured across a recent five-year period (a total of approximately 15,000 children), there are a variety of education outcomes that are significantly different from those of the general student population. For example, DCF involved children attend multiple schools, suffer chronic absenteeism, experience significant discipline incidents, and have a school dropout rate significantly higher than the general population of students. The high school graduation rate is significantly lower. All these outcomes are consistent with national literature discussed in Sidebar 1. As of the end of the 2017–2018 school year, Massachusetts counted approximately 6,800 school-age students5 in foster care or under state care, which are included in the statistics referenced above.

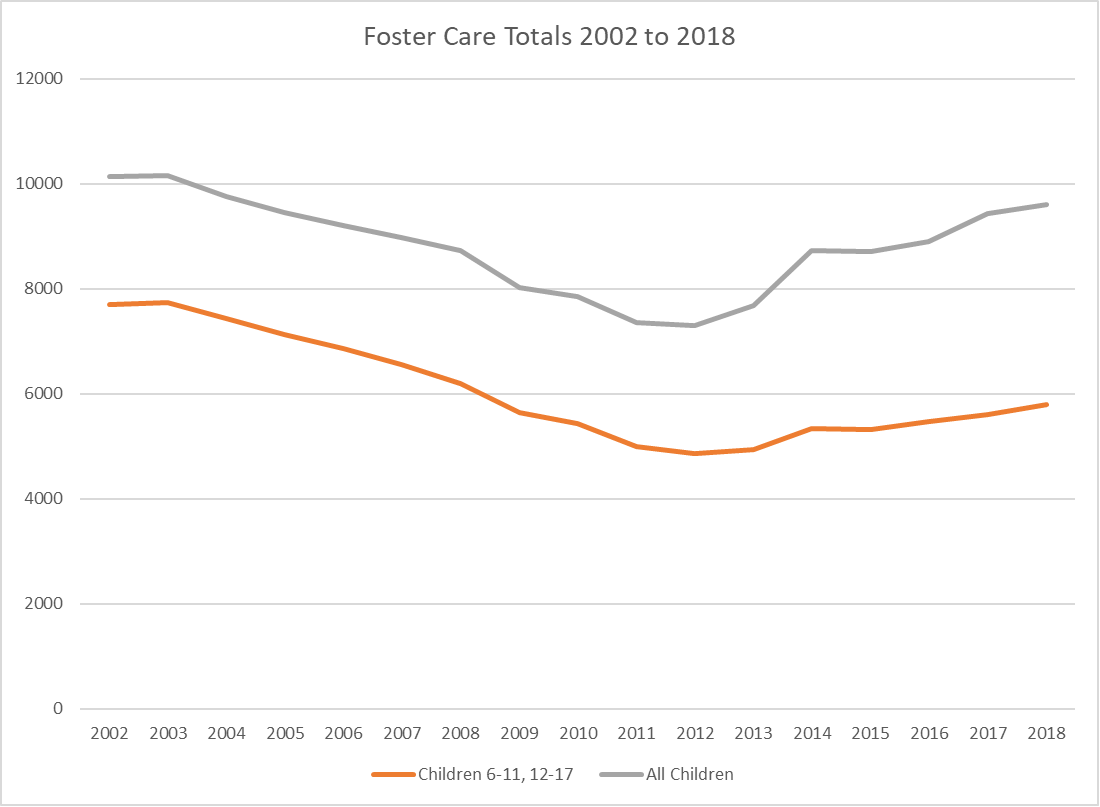

Both nationally6 and in the Commonwealth, the number of students in foster care declined from peaks reached in the early 2000s until the totals bottomed out in 2011–2012. Since that period, however, there has been a steady increase in the number of children in foster care. As shown in Table 1, the number of school-age children in foster care in Massachusetts has risen 20% since 2012.

Table 1—Number of school-age students in foster care in Massachusetts and all children in foster care.7 (Source: Massachusetts Department of Children and Families Quarterly Reports)

The trend in Massachusetts is similar to the trend nationally. The federal Administration of Children and Families reports that the top reasons for placement in foster care include neglect, parents with substance abuse problems, and caretaker inability to cope.8 Children in foster care are placed in a range of living situations with varying relationships. Some are placed with family members, others in traditional foster care families, and others in institutional or congregate care settings. The range of services required for educational success will vary among students and has a financial and operational impact on school districts. As discussed in the next section, the federal government provides protections for students that states and school districts must follow in the educational process.

Federal law and regulation has changed over the past decade

During the past decade, the legislative and executive branches of the federal government have taken steps to protect the overall welfare and educational rights of children in foster care. There have been two major pieces of legislation that contribute to the governance in this policy area. This section describes each in turn and discusses what changes in practice they have prompted at the state and school-district levels. The federal government has significant power in these areas because of the substantial funding it provides for both foster care and K-12 public education.

Fostering Connections Act

In October 2008, the US Congress passed, and President George W. Bush signed, the Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act. The law stated that educational success for students in foster care is dependent on the cooperation between child welfare agencies (CWA) and local education agencies (LEA).9 The law also included a commitment to allowing a student to remain in the school within the district of origin, unless a change is determined to be in the best interest of the child. As part of that commitment, it laid out the process by which the CWA, state education agency (SEA), and LEAs could apply for funds set aside for expenses related to transportation of students back to their school of origin if the student meets the Title IV-E requirements.10 11 However, the requirements for action in this law were directed to the CWAs instead of to state and local education agencies,12 as there was no impact of the law on education funding. The law did create an opportunity for the CWA and LEAs to cooperate on reimbursement for the transportation costs. Massachusetts is in the process of modifying its federal plan to allow for these expenses. The reimbursement may run as high as 25% of the $3.2 million expended by districts during the 2017–2018 school year. The district detail is included in Appendix E.

Every Student Succeeds Act

In December 2015, President Barack Obama signed the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA). ESSA reauthorized the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) and directed the federal government to strengthen the rights to educational services for students in foster care.13 The act returned attention to the role of SEAs and LEAs in supporting educational continuity for students in foster care transition. The federal legislation reaffirmed the commitment that CWAs and LEAs should cooperate on the best possible educational arrangement for students in foster care. The law’s default position is that a student should have the right to remain in their school of origin (the school the child was attending at the time of placement into foster care or before the most recent change in residential placement) absent a finding that it is in the best interest of the student to be enrolled in their placement community’s school system. This is an instruction consistent with the commitment to limit the educational transitions of students in foster care. It implies the need for transportation policies and resources to make the commitment of best interest a reality.

According to the ESSA, if a student is changing schools because of the best-interest determination, the student should be immediately enrolled in the local school, even when necessary documentation, such as the child’s special education plan or academic history, is not available. Further, the federal law states that the LEA and CWA should cooperate on transportation funding to the extent that school transportation is required for the student’s educational opportunity. The law also reaffirmed the availability of forms of reimbursement for transportation through Title I (ESEA) and Title IV (Social Security Act). However, the 2015 law does not allow for the provision of funds for educational services beyond those that are allowed under Title I.14 Title I authorizes the expenditure of funds for services to support students from low-income families, particularly those in danger of not meeting state educational standards.15 While Title I funds may be used to offset transportation costs for students in foster care, the limited funds are already allocated to educational services for these and other students; the reality is, therefore, that funds for transportation must come from another source.

The federal law includes a broad definition of “children in foster care,” stating that this legal category includes, “but is not limited to, placements in foster family homes, foster homes of relatives, group homes, emergency shelters, residential facilities, child care institutions, and pre-adoptive homes.”16 Massachusetts confirmed this inclusive approach in recent guidance from then–Acting DESE Commissioner Wulfson in conjunction with DCF.17

After the 2015 passage of ESSA, the Obama Administration worked to resolve and clarify various regulatory and guidance issues. A guidance document was published in June 2016 that required all local education agencies accepting Title I funds to provide a plan for transportation back to the district of origin unless another placement is deemed to be in the best interest of the child.18 Later in 2016, the US Department of Education released a summary letter and regulations related to ESSA that offered further explication of the division of financial responsibilities between LEAs and the CWAs. While the regulatory document tried to clarify how ESSA was supposed to operate regarding the details of transportation reimbursement, the regulations remain unclear because, at the beginning of the Trump Administration, the Congress passed and the President signed into law a disapproval bill pursuant to the Congressional Review Act.19 This leaves state and local education agencies without regulations and forced to interpret the language of the federal law regarding responsibility for transportation. This issue is discussed below in terms of the impacts on local school district services and budgets.

State law and regulation and the declining commitment to funding these services

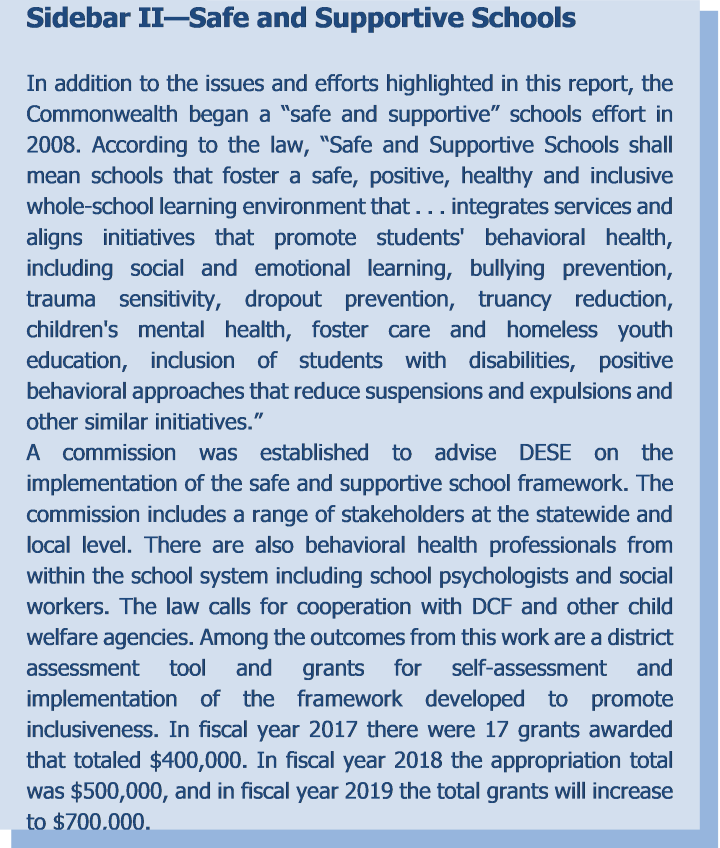

Because the state accepts funds from the federal government through Title IV-E of the Social Security Act for the foster care program and Title I of the ESEA for public schools, it must cooperate on the enforcement of federal rules. For example, because the law requires administrative resources to support these educational services, DESE has a coordinator for the education of foster children and DCF has an education coordinator. There is a broad array of requirements for rights to educational services under the state constitution, law, and regulation. For children in foster care, these rights are buttressed by general requirements for education in Massachusetts, as well as special provisions for their status in state care. Joint guidance was issued by DESE and DCF in January 2018 to clarify for school districts their responsibilities under federal and state law, including the appointment in each district of a point-of-contact for the education of students in foster care.

Chapter 70 formula and reimbursement for educational services

As shown in Appendix C, the state law regarding the education of children in foster care has been amended 17 times since its original passage in 1896. While some of the statutory revisions represent little more than nomenclature changes, some have been more substantial. In 1977, for example, the legislature extended reimbursement to cover costs for education in secondary schools in addition to the previous commitment for elementary grades. That commitment lives on in the current statute and—of equal importance—is included in Section 96 of Chapter 71 of the Acts of 1993 (a part of the Education Reform Act), this responsibility did not disappear as a result of the establishment of education reform in 1993 as the legislature continued to fund these provisions through fiscal year 2001 (see Appendix B).

In addition to the calculation of state aid for school districts based on enrollment, there are increases based on other demographic factors including the number of economically disadvantaged students in the school district. The count of foster children per district is included in the economically disadvantaged supplement. However, since the estimates from state child welfare and education officials ranges from 45% to 50% of the students in foster care requiring special education services (see the section below on special education services and costs), LEAs report that merely including these students in the “economically disadvantaged” count is insufficient to help pay the real cost of education. The details of the system are summarized in Table 2, below.

Section 7 of Chapter 76 of the Massachusetts General Laws (as described above on pages 4 and 5) was intended to provide a per-student reimbursement to communities for educating foster children using the average-per-pupil cost of educating a child in that community. The reimbursement provision covers those districts impacted by placements of children not previously residents of the community by paying them an amount, per placed student, equal to the average spent, per student, on all students in the district. The economically disadvantaged formula varies the amount depending on the demographics of the community, with some districts getting more funds and others less. In all cases, the total aid for a foster child would be less than the district spends to educate the child, as Chapter 70 funding varies based on the district’s overall enrollment and calculated ability to pay for the child’s education.

Table 2—Funding of educational services for students in foster care

|

Funding Source |

Issue/Challenge |

Shortfall |

|---|---|---|

|

Foundation Budget—Chapter 70 Aid |

The 6,800 children in foster care are mobile and may not remain in communities for long periods. May not be counted in October 1 census in proper districts. |

Districts are not receiving the reimbursement under Chapter 76, Section 7, which applies to students placed outside their district of origin. According to DESE, foundation budget formula replaces this reimbursement but does so at varying rates based on community characteristics. |

|

Foundation Budget—Economically Disadvantaged Supplement |

Students may have multiple placements during the year and therefore funds may not go to district offering services. |

Districts are concerned about the accuracy of the count. Children in foster care will have high service needs that cost more than reimbursement. |

|

Special Education Circuit Breaker |

Children in foster care experience higher use of IEP-related services than the student population as a whole. |

Reimbursement for foster students, homeless students, and wards of the state totaled $17 million in fiscal year 2017. In these cases, districts must absorb the first $44,000 of expenses (or four times the average statewide foundation budget amount). |

|

School Transportation |

Districts must pay to transport students from district of placement to district of origin. |

DESE reports from school districts during the |

|

Chapter 76, Section 7 Reimbursement |

MGL promises reimbursement for educational services provided to students placed by DCF in new district. |

This commitment has not been funded since fiscal year 2001. |

State regulations and determining the financially responsible district

In addition to legislative action, educational services for children in foster care / state care are also impacted by regulation. Effective July 1, 2018, the Board of Elementary and Secondary Education implemented amendments to state regulations20 that include clarifications on programmatic and financial responsibilities for districts involved in the education of students in foster care / state care. Updated in response to ESSA, the new set of regulations combines considerations for children in need of special education services with students in foster care / state care.

Among the 2018 changes is a redefinition of what constitutes the district financially responsible for the special education services of a student in foster care / state care. For students placed and attending school in a district other than the district of residence for the student’s birth parent(s) or guardian(s), the latter district is responsible for the costs of special education.21 This provision offers a set of solutions for the potentially complex process of determining the residence of the parent(s)/guardian(s) of children in foster care / state care. The state has the authority to assign responsibility for the student to a district under certain limited circumstances.22 Moreover, the regulations provide for the circumstance in which the custodial parent or guardian “resides in an institutional setting in Massachusetts, including, but not limited to, a correctional facility, a hospital, a nursing home or hospice, or a mental health facility, a halfway house, a pre-release center or a treatment facility.”23 The district of residence before commitment is the responsible party. This decision has a major impact on district finances and therefore also increases the incentive for districts to challenge the determination of responsible district. This is a question resolved by DESE, which estimates there are 400 such determinations each year for the totality of students in special education. DESE has also confirmed that it has decided on 73 such appeals so far this academic year for students in foster care and it characterizes this as an “uptick.”24

The school district determined to be financially responsible absorbs the special education costs (up to four times the statewide average of the foundation budget amount or what is approaching $46,000 per year) and transportation costs (see below), and the complex nature of reimbursements may mean that the districts are underfunded or improperly funded.

Transportation funding and arrangements impacts educational stability

ESSA created a window in which SEAs were to implement the educational stability provisions of the law. For Massachusetts, this implied a change in practice for the documentation of transportation expenses related to maintaining relocated students in their schools of origin. ESSA recognized the challenges faced by districts in maintaining students in appropriate educational settings and called for close cooperation between the CWA, SEA, and LEA to ensure enrollment in the school of origin or proper placement in the new district of residence. Under ESSA, educational placement remains a joint decision of the parties, but the availability and cost of transportation should not be a factor in the decision, while time of transportation can be a consideration.25 Further, ESSA requires LEAs receiving Title I funds to collaborate with the SEA and CWA to “develop and implement clear written procedures governing how transportation” for children in foster care will be provided.26 This is a critical issue as there are resources required to transport a child back to the district of origin and to maintain educational stability.

The DESE/DCF guidance states that “Absent other agreements between districts and DCF, the district of origin is responsible for providing transportation to and from the school of origin.” This squarely places the financial burden of transportation on the school districts. Yet the federal law is explicit regarding this issue: in the absence of funding from the CWA or agreement between the CWA and LEA, the LEA is not responsible for providing transportation for students beyond its normal requirement.27 This means districts must accommodate students on a normal route or with small variation of an existing route. Nothing in law justifies the expanded mandate for school districts to absorb out-of-district transportation expenses for these students. Districts are absorbing the cost of transportation for many students in the process of bringing them back to their district of origin in order to maintain educational stability.

School districts are continuing to wrestle with these and similar categories of transportation expenses. Several requirements under Massachusetts law mean that school districts provide transportation beyond the district including McKinney-Vento homeless students, special education students in various out-of-district programs, vocational-technical students studying out of district, and students in charter schools. Districts report difficulty sustaining these transportation requirements, particularly for one-to-one trips out of district. This difficulty is especially acute for longer distances and as the districts get closer to the end of the school year. A variety of factors can exacerbate the challenges, including a shortage of trained drivers (particularly those that can transport students with special needs) and a lack of competitive bidders on school transportation contracts in general. Sometimes these efforts are deemed ineligible for reimbursement by the Commonwealth or the reimbursement covers only a small percentage of cost despite provisions in Massachusetts General Law that promise higher levels of support. Although both McKinney-Vento and regional school district transportation costs are supposed to be fully reimbursable, state support in both categories is subject to annual appropriation. In fiscal year 2017, the school districts and municipalities in Massachusetts spent over $744 million on school transportation as shown in Table 3.

Table 3—Massachusetts School Transportation Breakout fiscal year 2017 from DESE Schedule 7

|

Sum of Amount |

Description |

Reimbursable? |

Actually Reimbursed? |

Law |

|

|

4000 |

$280,101,015 |

In-District Regular |

Y>1.5 mi |

Y, RSD only |

MGL Chapter 71, Section 7A, 7B; MGL Chapter 71 Section 16C also Island Children |

|

4010 |

2,039,953 |

Out-of-District Regular |

Y>1.5 mi |

N |

MGL Chapter 71, Section 7A, 7B; MGL Chapter 71 Section 16C also Island Children |

|

4020 |

2,806,542 |

Regular Preschool |

Y>1.5 mi |

N |

MGL Chapter 71, Section 7A, 7B; MGL Chapter 71 Section 16C also Island Children |

| Regular Subtotal | $284,947,510 | ||||

|

4070 |

42,406,795 |

3-5 year old |

Y |

N |

MGL Chapter 71B, Section 14 |

|

4080 |

164,888,718 |

Public School programs 6-21 |

Y |

N |

MGL Chapter 71B, Section 15 |

|

4110 |

51,622,949 |

Public Separate day school 6-21 |

Y |

N |

MGL Chapter 71B, Section 16 |

|

4120 |

60,955,871 |

Private Separate day school 6-21 |

Y |

N |

MGL Chapter 71B, Section 17 |

|

4130 |

3,204,130 |

Private Residential school 6-21 |

Y |

N |

MGL Chapter 71B, Section 18 |

|

4140 |

652,986 |

Homebound/ |

Y |

N |

MGL Chapter 71B, Section 19 |

|

4150 |

601,451 |

Public Residential Institutions 6-21 |

Y |

N |

MGL Chapter 71B, Section 20 |

|

Special Education Subtotal |

$324,332,900 |

||||

|

4190 |

32,342,954 |

VoTech In-district |

Y > 1.5 mi |

N |

MGL Chapter 71 Section 16C |

|

4200 |

4,410,191 |

VoTech Out-of-district |

Y |

Y |

MGL Chapter 74, Section 8A |

|

VoTech Subtotal |

$36,753,145 |

||||

|

4220 |

6,779,059 |

Non-public In-district |

N |

||

|

4230 |

256,343 |

Non-public Out-of-District |

N |

||

|

Non-Public Transportation Subtotal |

$7,035,402 |

||||

|

4250 |

1,916,923 |

Racial imbalance |

Y |

N |

MGL Chapter 76, Section 12A |

|

Racial Imbalance Subtotal |

$1,916,923 |

||||

|

4260 |

$784,940 |

Day care transport |

N |

N |

|

|

4270 |

$981,633 |

Other education programs including adult |

N |

N |

|

|

4280 |

$18,093,320 |

Out-of-district Choice and Charter |

Y |

N |

Chapter 76, Section 7B |

|

4283 |

10,917,554 |

Homeless Student Out-of-district |

Y |

Y |

Mandate determination 2011 |

|

4285 |

13,233,096 |

Homeless Student Transportation |

Y |

Y |

Mandate determination 2011 |

|

Homeless Subtotal |

$24,150,650 |

||||

|

4310 |

8,216,990 |

Reg Transit Assessment |

|||

|

4320 |

37,381,490 |

Transportation services including METCO |

Grants |

||

|

Grand Total |

$744,594,902 |

(Source: DESE Annual Report Schedule 7 FY 2017)

Against that $744 million total, the state reimbursed school districts the following amounts in fiscal year 2017:

- $63 million for regional transportation to academic regional school districts and vocational-technical school districts;

- $8.35 million for McKinney-Vento homeless student transportation; and

- $250,000 for out-of-district vocational-technical transportation.

Total reimbursement thus represents less than 10% of overall local spending on school transportation. Moreover, transportation is not an allowable category of expense against required school spending by districts (similar to capital expenses, grants, and revolving funds). Another way of looking at the $744 million is that it represents 12.55% of spending beyond the requirement for a local contribution for fiscal year 2017.28

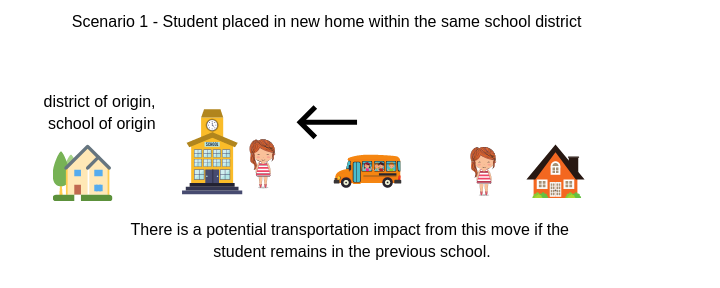

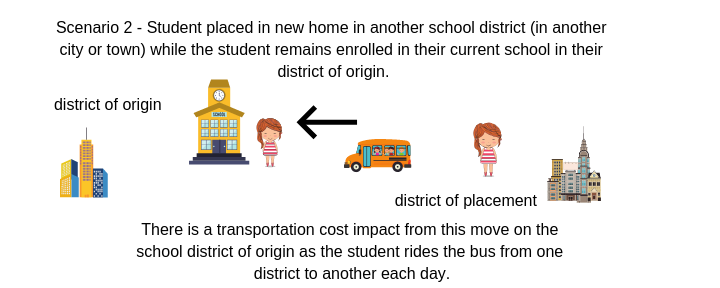

The school year that ended in June 2018 was the first year that Massachusetts added the category of transportation for foster children educated in the school or district of origin and subject to transportation to its reporting of education expenses by district. The total reported by districts amounts to just over $3.2 million. These are the students identified in Scenarios 1 and 2 below. Federal and state law require the ability for students in foster or state care to stay not just in their districts of origin but also in their schools of origin. This implies that there will be some intra-district, as well as the reported inter-district, transportation costs if the student is living in a school zone different from the one of enrollment. This number will increase as districts get more accustomed to the reporting requirement and any applicable reimbursement policy.

School districts provide critical services for students in foster care with few additional resources

School districts in the Commonwealth provide a deep set of educational and support services to children in foster care and manage compliance with federal and state law and regulation. For example, each district is required to have a foster care point of contact in addition to a homeless student education point of contact. With limited resources, school districts navigate the requirements for the success of their students in foster care. Central to this challenge is the participation of districts in the best-interest determinations for student educational placements. There are three broad scenarios for making these decisions about where students in foster care should attend school and what services are necessary for the child’s success. Each of these scenarios has the possibility of generating a different set of financial and programmatic impacts:

Scenario 1—The student is placed in foster care within the same school district where they lived before entering foster care or because of change in foster care placement. There is no tuition impact, but there is a potential transportation impact under current law if the student requires transportation outside the norm offered to any student in the district, e.g., there is no bus route between the new home and the child’s original school.

Scenario 2—The student is placed in foster care in a school district other than the one where they are currently enrolled while the student remains in the school / district of origin. There isa transportation impact because the district of origin must bus the student to and from the new residence, but there is no tuition impact under current law.

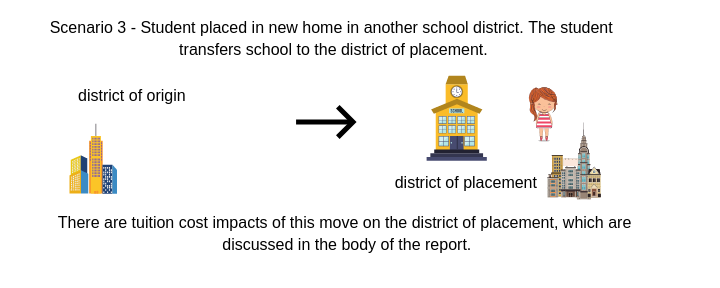

Scenario 3—The student is placed in foster care in a school district other than the one where they are currently enrolled and enrolls in the new district appropriate to the residence of the foster family or group home. There is a tuition impact because the new district has to fund the student’s education, but there is no transportation impact under current law.

Financial impacts on districts

The students covered by scenario 3 are those who should be addressed by the funding offered by Section 7 of Chapter 76 of the Massachusetts General Laws. Given the mobility of the students and their families, it is difficult for districts to track down the information on the previous residence of the birth families and determine the district of origin for students in foster care. This system of allocating costs has a substantial financial impact on districts receiving students with high special needs, as these vulnerable children are relatively costly to educate. The current system for school finance which is based on the school census of October 1 and the foundation budget formula does allocate some level of state aid to districts providing educational services to students in foster care (assuming that students are not reassigned during the year). The amount of money is related to the number of students in foster care and the level of foundation aid (Chapter 70) received by the community.29 The foundation budget system approaches funding from a different perspective than the one framed by laws related specifically to educational services for students in foster care. It is, however, consistent with the legislative language implemented in recent years regarding the Chapter 70 formula (which is updated each year in an outside section of the budget).30 It leaves districts with significant expenses for education and support services, as well as special education costs.

Best-interest determinations require collaborative decision-making.

According to federal law and state guidance, both the district of origin and the district of placement should participate in best-interest determinations for students in foster care. The January 2018 guidance, cited above, includes DCF, the districts, parents/guardians, and education decision-makers as participants in the best-interest determination discussions. Because of the cost implications and complexity of these decisions, such collaboration is important to arrive at the correct decision for the student’s academic life and to properly weigh potential challenges for the student. Some of these students face deep emotional challenges that require high-level interventions because of trauma from family actions and separation.31 School districts reported that the best-interest meetings were not an interactive process, and school districts were not encouraged to participate in a meaningful way. District officials reported that even when they were consulted, DCF did not take account of their feedback on what the district believed was in the best educational interest of the student. Additionally, some school district officials believed that the best-interest determination needed to have a formalized process, which they believed was currently lacking. While this process may take time, DESE/DCF guidance reinforces that the student should continue to attend the school of origin while the best interest is being determined.

Special education services and costs

There are substantial numbers of children in foster care that require special education services. DESE estimates that approximately 45% of the students in foster care require an Individualized Education Plan (IEP), which results in a range of additional services for children. Some of these requirements can be met by in-district resources, while others may result in out-of-district placements in collaboratives or private schools, including residential settings. Costs for these out-of-district placements can vary from $50,000 per year for placement in out-of-district day schools to over $300,000 for residential placements.

Districts providing special education services to students in foster care placed in their schools may use the special education bill-back process.32 This means that districts with programmatic responsibility can bill the districts that, under regulation, bear the financial responsibility for educating these students. While this does occur in some cases under established DESE procedures (across the entirety of special needs students, not just foster care), some districts report that they do not actually receive the payments for which they are eligible. DESE and some districts have also indicated that there are informal agreements among districts not to bill each other for these services, due to the costs of the administrative services necessary to effectuate the payments, and the belief that over time the in-district special education costs will even out. However, for higher-cost, out-of-district placements, the private schools or special education collaboratives bill the financially responsible district directly.

These placement decisions are often made without the participation of the district that is financially responsible for the student. (When the student is attending school in the district of foster care placement, the district of origin remains financially responsible for the special education costs—see the graphic for Scenario 3.) There is also special help to districts that host students who have high special needs that trip the special education circuit breaker.33 These districts receive 100% reimbursement of costs above four times the statewide average of the foundation budget (roughly $11,000 x 4). To receive the higher level of state reimbursement, districts must properly identify students as being in foster care, homeless, or in state custody. The total for fiscal year 2018 for students in these categories was over $17 million. In addition, as noted earlier, the special circumstances of children in foster care make them statistically more likely to qualify for other forms of special needs support, since they may also be English language learners, homeless, or simply struggling to maintain pace educationally with their peers.

Collaboration on behalf of the student is required according to federal and DCF education regulations, which stipulate that the social worker be excluded from decision-making on behalf of the student with an IEP or under evaluation for an IEP.34 This implies important roles for the parent, foster parent / guardian, or Special Education Surrogate Parent as well as coordination with school district personnel. School districts report that the Special Education Surrogate Parent program does help with the process and results in stronger plans for the student.

Unfunded mandates and Section 7 of Chapter 76 of the General Laws

On March 28, 2018, the Mayor of Greenfield petitioned the State Auditor’s DLM regarding the Commonwealth’s failure to reimburse the Greenfield Public Schools for educational services provided to students in foster care in out-of-district placements covered by the provisions of G.L. c. 76, § 7.35 Greenfield indicated that in fiscal year 2015, it spent $709,931.24 to provide educational services to students placed in foster care in Greenfield. Greenfield believed that the failure to fund the provisions of Section 7 imposed a direct service or cost obligation on the Greenfield Public Schools in contravention of the Local Mandate Law, G.L. c. 29, § 27C. The dollar figure from Greenfield came from applying the formula posed in G.L. c. 76, § 7 (average cost to educate all students in the district times the number of students educated in their schools whose district of origin was not Greenfield). This is an illustration of Scenario 3 from above.

|

Number of Pupils |

Tuition Cost |

Total |

|---|---|---|

|

47 |

$15,104.92 |

$709,931.24 |

This is not the first time DLM has received a petition regarding G.L. c. 76, § 7. In 1989, DLM received a petition from the City of Worcester that raised 11 items of concern, including issues related to special education notifications, language education in schools, and testing preparation.36 37 38 These issues were later reviewed by the Supreme Judicial Court in 1994.

Application of the Local Mandate Law to Foster Care Student Reimbursement under G.L. c. 76, § 7

In general terms, the Local Mandate Law, G.L. c. 29, § 27C, provides that any post-1980 state law, rule, or regulation that imposes additional costs upon any city or town must either be fully funded by the Commonwealth or be made conditional to local acceptance. Pursuant to the Local Mandate Law, any community aggrieved by an unfunded state mandate may petition the Superior Court for an exemption from complying with the mandate until the Commonwealth provides sufficient funding. Before taking this step, a city or town may request an opinion from DLM as to whether the Local Mandate Law applies in a given case and, if so, a determination of the cost for complying with the unfunded mandate. DLM’s deficiency determination is prima facie evidence of the amount of funding necessary to sustain the local mandate.39 Alternatively, a community may seek legislative relief. However, the Local Mandate Law does not apply to all laws governing local activity. Laws that notably fall outside the scope of the Local Mandate Law are federal laws and regulations and laws regulating the terms and conditions of municipal employment.40

To determine whether the anticipated local cost impact of a state law, rule, or regulation is subject to the Local Mandate Law, we apply the framework for analysis developed by the Supreme Judicial Court in City of Worcester v. the Governor. Of particular relevance to this petition, the challenged law must take effect on or after January 1, 1981; must be either a new law or a change in a law that rises to the level of a new law; and must result in a direct service or cost obligation that is imposed by the Commonwealth, not merely an incidental local administration expense.41 Moreover, the legislature, in enacting the challenged law, must not have expressly overridden the Local Mandate Law.42

In 1994, the Supreme Judicial Court reviewed whether Section 7 of Chapter 76 of the General Laws is an unfunded mandate in Worcester. In the Worcester decision, the Supreme Judicial Court found that G.L. c. 76, § 7 did not constitute an unfunded mandate because the 1983 amendments to Section 7 of Chapter 76 did not constitute substantive amendments that imposed new obligations on Worcester.43

Reviewing this matter in the light of the Supreme Judicial Court’s decision, the post-1980 amendments to Chapter 76, § 7 do not impose any new obligations on Greenfield that would trigger the Local Mandate Law. The state’s assurance that it will pay for the education of students in state care that are placed in a school district other than their home school district dates back to 1896.44 45 While Section 7 of Chapter 76 has been amended numerous times over the years, the last substantive amendment occurred in 1978 and required the state to reimburse a school district for the educational expenses of all children placed by the state in foster care outside their home town; previously, reimbursements were only for children over the age of 5.46 To trigger the Local Mandate Law, there must be a change in a state law, regulation, or rule that imposes a new obligation on a city or town. Since there have been no substantive post-1980 changes that impose a new obligation on Greenfield, the Local Mandate Law does not apply to G.L. c. 76, § 7.

Summary

We have reviewed significant issues regarding the roles of the major participants and policymakers who contribute to choices about providing and paying for educational services for children in foster care. These roles and some of the major issues are presented in Table 4. Highlighted is the need for closer cooperation between state agencies and school districts on decisions affecting the educational placement and services required by the children in foster care. Lack of resources, both money and time, contributes to the disconnection. In the following section of the report, we discuss findings and recommendations aimed at improving the provision of services, efficiency of serving student needs, and a more equitable funding stream for local services.

Table 4—Roles and responsibilities of participants in the education of students in foster care

|

Policy Participant |

General Responsibility |

Challenge |

Governing Documents |

|

Local School Department |

Classroom instruction |

6,800 students statewide |

Mass. Const., Part II, c. 5, § 2; G.L. c. 69, § 1; McDuffy v. Sec’y of Executive Office Educ., 415 Mass. 545, 606 (1993) and G.L. c. 69, § 1. |

|

Local School Department |

IEP |

Roughly half of students in foster care require special education IEPs |

Special Education Regulations, 603 CMR 28.10 |

|

Local School Department |

Mental health counseling services |

||

|

Local School Department |

Counseling services for placement and to gain academic credit for previous courses in other districts |

||

|

Local School Department |

Transportation to school of origin |

Unreimbursed expense |

January 2018 document by DESE and DCF, previous training |

|

Local School Department |

Out-of-district placements to collaboratives or special schools |

Students in foster care have a higher than average incidence of these placements |

Special education regulations, 603 CMR 28.10 |

|

Local School Department |

Determines financial responsibility of district based on residence of parents |

Requires knowledge of community of origin of parents at time of child’s entry into foster care |

Revised DESE regulations July 2018 |

|

Local School Department |

Determines program responsibility based on residence of student |

Revised DESE regulations July 2018 |

|

|

DCF |

Supervision of foster care program |

||

|

DCF |

Residential Placements |

||

|

DCF |

Transportation funding |

Providing transportation services through social workers and contractors, no reimbursement to local districts |

January 2018 document by DESE and DCF, previous training, federal laws |

|

DCF |

Best-interest determination |

Uneven implementation of cooperative decision-making |

|

|

DCF |

Sets standards with DESE for educational services for foster children |

January 2018 document by DESE and DCF |

|

|

DESE |

Sets standards with DCF for educational services for foster children |

January 2018 document by DESE and DCF |

|

|

DESE |

Collects data on educational performance, transportation costs |

First year coming |

|

|

DESE |

Provides dispute resolution on financial and programmatic responsibility |

||

|

Federal Government |

Law and regulation regarding foster care, from 2008 |

Foster Connections Act promotes educational stability |

Public Law No: 110-351 (10/07/2008) |

|

Federal Government |

Law and regulation regarding education services, from 2015 |

ESSA broadly defined students in foster care |

Public Law No: 114-95 (12/10/2015) |

| Date published: | April 23, 2019 |

|---|---|

| Last updated: | April 23, 2019 |