- Scientific name: Gomphurus ventricosus

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Threatened (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Male skillet clubtail

The skillet clubtail is a large, semi-aquatic insect in the order Odonata, suborder Anisoptera (the dragonflies) and family Gomphidae (the clubtails). The clubtails are a large, diverse group of dragonflies named for the lateral swelling at the tip of the abdomen that produces a club-like appearance which varies greatly among species. Clubtails are further distinguished from other dragonflies by their widely separated eyes, wing venation characteristics, and behavior. Many species are very elusive and are thus poorly known. The midland clubtail is in the genus Gomphurus (the majestic clubtails), a group of medium- to large-sized dragonflies characterized by having the broadest clubs of any of the Gomphidae. Skillet clubtails are dark brown dragonflies with pale yellow to greenish markings on the body, blue-green eyes, and blackish legs. The thorax is marked with thick, pale stripes that form a rearward-facing U pattern dorsally and broad, pale, lateral stripes. The pale thoracic markings are bright yellow in immatures but darken to a dull grayish-green in mature individuals. The dark abdomen has thin, yellow markings on the tops of segments one through seven, and yellow patches on the sides of the club. The face is plain, dull yellowish. The sexes are similar in appearance, though the females have thicker abdomens and a less developed, though still prominent, club.

Adult skillet clubtails range in length from 45-53 mm (1.8 -2.1 in), with a wingspan averaging 63 mm (2.5 in). It’s the smallest majestic clubtail with the widest club found in Massachusetts. The fully developed nymphs range from 24-28 mm (~1 in) in length.

The skillet clubtail is one of three species in the genus Gomphurus in Massachusetts. The other two, the cobra clubtail (Gomphurus vastus) and midland clubtail (G. fraternus), are very similar in appearance. As in most clubtails, the shape of the male hamules (located on the underside of the second abdominal segment) and terminal appendages, and the female vulvar laminae (located on the underside of the eighth and ninth abdominal segments) provide the most reliable means for identification. Skillet clubtails are the smallest and most slender of the three Gomphurus species in the state, but have the widest club, giving them a distinctive shape. The skillet clubtail has a plain yellow face, without the black cross-striping present on the cobra clubtail, and lacks the yellow spot on the top of abdominal segment eight that characterizes the midland clubtail. The pale stripes on the top of the thorax are thicker than on the other two species. The nymphs and exuviae can be distinguished by characteristics of the palpal lobes on the labium, as per the keys in Walker (1958), Soltesz (1996), Needham et al. (2000), and Tennessen (2019).

Life cycle and behavior

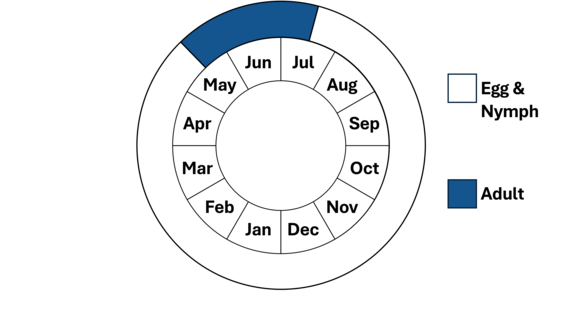

Note, nymphs are present year-round.

Skillet clubtails are elusive and little is known about their life history. The egg and nymph life stages are fully aquatic. The nymphs burrow into muddy and sandy substrate and are predators, feeding on a wide variety of aquatic insects, small fish, and tadpoles. Nymphs undergo several molts (instars) for at least 2 years until they are ready to emerge as winged adults. When ready to emerge, the nymphs crawl out onto exposed rocks, emergent vegetation, partially submerged logs, or the steeper sections of riverbanks, where they emerge from the nymphal exoskeleton as adults (a process known as eclosion). Emergence generally takes place very early in the morning, presumably to reduce exposure to predation. As soon as the freshly emerged (teneral) adults are dry and the wings have hardened sufficiently, they fly off to seek refuge in the vegetation of adjacent uplands, leaving their larval exoskeletons behind. These cast exoskeletons, known as exuviae, are identifiable to species and provide a reliable, useful means of determining species presence.

The immature dragonflies spend several days or more feeding and maturing in upland areas, before returning to their breeding habitats. Adult clubtails feed on aerial insects, including other dragonflies, which they capture in short sallies from their perches. When mature, the males return to the water where they can be found resting on sandy stretches of shoreline, roads, or perched on overhanging vegetation. They periodically make flights out over the water, particularly over rapids and riffles, presumably to search for females. Females generally appear at water only for a brief period when they are ready to mate and lay eggs. When a male encounters a female, he attempts to grasp the back of her head with claspers located on the end of his abdomen. If the female is receptive, she allows the male to grasp her, then curls the tip of her abdomen upward to connect with the male secondary sexual organs located on the underside of the second abdominal segment, thus forming the familiar heart-shaped “wheel” typical of all Odonata, with the male above, the female upside down underneath. In this position, the pair flies off to mate, generally hidden high in nearby trees where they are less vulnerable to predators. The duration of mating in skillet clubtails has not been recorded, but in similar-sized odonates can range from several minutes to an hour or more. Females oviposit by flying low over the water, periodically striking the surface with the tips of the abdomen to wash off the eggs. They seem to prefer the more turbulent areas of rivers and lakes for oviposition. It is not known how long the eggs of skillet clubtails take to develop.

Skillet clubtails have a rather short flight season with emergence beginning in late May and early June and adults flying into July.

Distribution and abundance

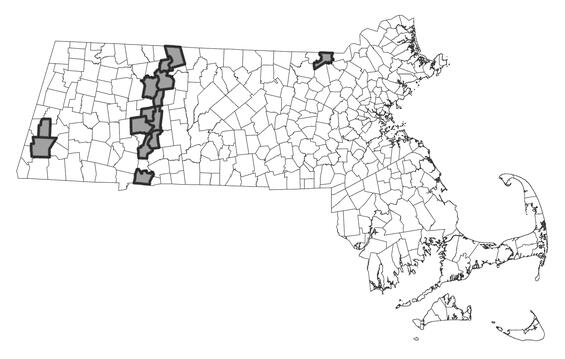

Skillet clubtails range throughout northeastern North America from Tennessee north to New Brunswick and Nova Scotia west into the Great Lakes region and south to Missouri. They appear to be scarce throughout their range. In New England, the species has been recorded in Vermont, New Hampshire, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. In Massachusetts, the species occurs in the Housatonic, Middle Connecticut, and Merrimack River watersheds, primarily in the mainstems of these systems. Recent surveys documented the species in the Merrimack River. Skillet clubtail is almost always observed in low abundances, whether exuviae or adults. The species status remains uncertain in Massachusetts.

The skillet clubtail is not often recorded in Massachusetts and is listed as Threatened. As with all species listed in Massachusetts, individuals of the species are protected from take (picking, collecting, killing, etc.) and sale under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act.

Distribution in Massachusetts.

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Skillet clubtails inhabit medium to large-sized streams with a mix of mesohabitats with fine sediment depositional areas and rocky areas with moderate streamflow. Adults also inhabit riparian areas, clearings, and uplands away from the nymphal stream.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Large and medium-sized stream habitat for skillet clubtail.

Threats

Degradation of water quality, alteration of natural streamflows, and upland habitat loss are primary threats to midland clubtail. Potential threats to the water quality of the include industrial and agricultural pollution, sewage overflow, salt and other road contaminant run-off, and siltation from construction or erosion. The alteration of natural flow regimes by damming, water diversion and water drawdown on skillet clubtails and other riverine species is unknown but may be considerable. Extensive use of power boats and jet skis that generate large wave action is a serious concern, particularly during the early summer emergence period of skillet clubtails (as well as several other clubtail species). Many species of clubtails, as well as other riverine odonates, eclose low over the water surface on exposed rocks, emergent or floating vegetation, or steep sections of the riverbank where they are imperiled by the wakes of high-speed watercraft.

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

Surveys should target known sites, new waterbody segments, and new waterbodies to update skillet clubtail occupancy and population status in Massachusetts. Targeting exuviae and adults will likely yield increased species detection and should target potential emergence and flight periods respectively. Occupied waterbodies should be routinely monitored every five years or to the extent practical to document changes in occupancy and habitat conditions. Effort should also target potentially suitable habitat into other medium-sized rivers throughout the state.

Management

Upland and waterbody habitat protection is critical for the conservation of skillet clubtail. Protection of forested riparian and uplands are critical in maintaining suitable water quality and are critical for feeding, resting, and maturation. Development of these areas should be discouraged, and the preservation of remaining undeveloped uplands should be a priority. Alternatives to commonly applied road salts should tested to minimize freshwater salinization. Altered streamflows and water levels from hydroelectric operations and water withdrawal should be minimized. Rapid changes in water level increase or decrease may cause mortalities during eclosion or become stranded during the nymph life stage. Hardened bank segments should be restored to promote natural sediment dynamics.

Research needs

Continued effort is needed to define habitat requirements, distribution, relative abundance, and potential breeding sites to update the species status in Massachusetts. Estimation of detection and occupancy rates and how other environmental variables (e.g., sample timing, weather) affect these rates is needed. Further research is also needed on their emergence and eclosion behavior to quantify species risk to regulated water levels.

References

Dunkle, S.W. 2000. Dragonflies through Binoculars. Oxford University Press.

Lam, E. Dragonflies of North America. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2024.

Needham, J.G., M.J. Westfall, Jr., and M.L. May. 2000. Dragonflies of North America. Scientific Publishers.

Nikula, B., J.L. Ryan, and M.R. Burne. 2007. A Field Guide to the Dragonflies and Damselflies of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program.

Paulson, D. Dragonflies and Damselflies of the East. Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press, 2011.

Soltesz, K. 1996. Identification Keys to Northeastern Anisoptera Larvae. Center for Conservation and Biodiversity, University of Connecticut.

Walker, E.M. 1958. The Odonata of Canada and Alaska, Vol. II. University of Toronto Press.

Tennessen, K. Dragonfly Nymphs of North America: An identification guide. Springer, 2019.

Contact

| Date published: | April 7, 2025 |

|---|