Standard VII

Judges should familiarize themselves with available treatment options for substance use disorders, mental health conditions, and co-occurring disorders, and when such a condition is a factor in a case, should consider ordering treatment, if appropriate and if authorized by law. Court-ordered treatment should match a party's treatment needs and should be selected based on clinical input identifying the type of evidence-based treatment that will work best for the party, with full consideration of public safety.

Commentary

In cases where the court has authority to order treatment, and only when a substance use disorder, mental health condition, or co-occurring disorder is a factor in the case, the court should use that authority to order treatment or impose treatment conditions.

Treatment orders may be made in certain types of cases as provided by law, but in many types of cases, judges do not have authority to enter orders for assessment or treatment. Detailed information on case types in which orders for assessment or treatment may be entered appears below.

Criminal Cases

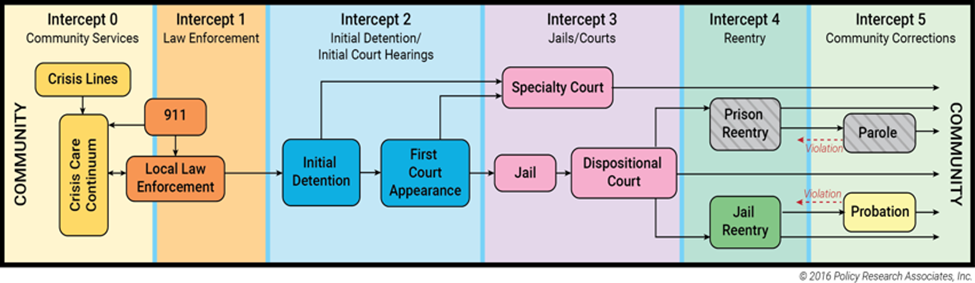

One way to think of the criminal justice system is as a series of points of potential “interception” where an intervention can occur to prevent certain individuals from entering or becoming more court-involved. A conceptual framework for communities to organize targeted strategies for justice-involved individuals with substance use disorders, mental health conditions, or co-occurring disorders is the Sequential Intercept Model (SIM).

The Sequential Intercept Model

While Standard VII focuses on the responses available to courts that are modeled at Intercepts 2 and 3, other actors in the community justice system also have a role to play at other intercept points, and judges should be aware of this model, as it can help them identify local resources and gaps in services; decide on priorities for change; and develop strategies to increase connections to treatment and recovery support services.

A. Pre-Trial and Diversion (Intercept 2)

- G. L. c. 111E, § 10, authorizes a judge to dismiss certain drug offenses if the defendant consents to assignment to a drug treatment facility and successfully completes the treatment program.

- District and Boston Municipal Courts have the authority to divert criminal defendants to pretrial diversion programs, which may have alcohol, drug, or mental health treatment as a component. G. L. c. 276A, §§ 1-9. If a defendant successfully completes the diversion program, the case may be dismissed.

- At the pretrial stage, the court may, with the defendant's consent, place the defendant on pretrial probation with alcohol, drug, or mental health treatment and testing as a condition of probation. G. L. c. 276, § 87.

- In cases involving actual or potential physical harm to a family or household member, the judge may set any conditions in lieu of or in addition to bail or personal recognizance that will ensure the safety of the person suffering or threatened with abuse and will prevent its recurrence. G. L. c. 276, §§ 42A, 58. Substance use disorder treatment or mental health treatment can be ordered as a condition.

- In cases involving certain crimes, the Commonwealth may move for pretrial detention or release on conditions under G. L. c. 276, § 58A. In these cases, a judge may, depending on findings, decide to hold a defendant without bail pending trial, release the defendant on bail or personal recognizance, or release the defendant under certain conditions, which may include ordering the defendant to refrain from the use of alcohol or drugs, or undergo a drug, alcohol, or mental health assessment and treatment. G. L. c. 276, § 58A.

- Bail revocation hearings for violations of pretrial conditions of release may provide the court with an opportunity to assess the conditions of release based upon substance use disorders, mental health conditions, or co-occurring disorders of a defendant, and order treatment, if appropriate.

- If it is appropriate to hold a defendant in custody in lieu of bail, a judge should provide information to custodial authorities, including on the mittimus if appropriate and being mindful of privacy concerns, when there is a safety issue or a serious risk of harm to the individual being transported, or to others.

B. Pre-Sentencing (Intercept 3)

- After a finding of guilty and prior to sentencing a defendant, a judge may order an assessment of the defendant to aid in sentencing. G. L. c. 123, § 15 (e). This can be particularly helpful where the relationship between mental health and substance use disorder issues needs to be clarified.

- A judge may postpone sentencing to enable MPS to prepare a pre-sentence report that details the defendant's substance use disorder and/or mental health history, including treatment needs and prior or current efforts to seek treatment. Mass. R. Crim. P. 28(d)(2).

C. Sentencing (Intercept 3)

When structuring a sentence for a defendant who has a substance use disorder, mental health condition, or co-occurring disorder the judge should keep in mind that recurrence of use or symptoms is common and may fashion a sentence that leaves room for the application of more intensive treatment. Court departments with criminal jurisdiction have each developed sentencing best practices that are rich with information, and judges should consult the best practices principles applicable to their department.

The court has broad discretion in setting conditions of probation for any defendant that are reasonably related to the underlying offense, which may include substance use disorder treatment up to and including a residential treatment program. G. L. c. 276, §§ 87, 87A. The sentencing of defendants charged with first and second offenses involving operating motor vehicles under the influence of alcohol or drugs creates opportunities for court-ordered treatment that are explicitly prescribed by statute. G. L. c. 90, § 24 et seq.

When a defendant is convicted of more than one charge, the judge can set a foundation for the application of escalating responses to non-compliance by imposing a combination of different sanctions for the different charges - e.g., a split sentence to the House of Correction, probation concurrent with or on and after a committed sentence, a combination of straight probation with probation conditions, or different lengths of suspended sentences imposed on and after one another, when authorized by the statutes governing sentencing for each offense.

D. Specialty Courts (Intercept 3)

Specialty courts seek to address the unique and often overwhelming needs and challenges faced by court-involved individuals who suffer from behavioral health issues. The purpose of specialty courts is to remove barriers that impede recovery, to encourage access and engagement in behavioral health treatment, and to provide court support that enables individuals to remain in the community and avoid hospitalizations and custodial detention. Specialty courts are often referred to as “problem solving courts.” They offer a non-adversarial approach and alternative model to traditional court proceedings and protocols. Participation in a specialty court is always voluntary; after consultation with counsel, a defendant may accept participation as a term of pre-trial probation or as a condition of post-disposition probation. The Trial Court has specialty courts to address substance use disorders and mental health conditions, as well as specialty courts focused on particular populations such as veterans, homeless individuals, and defendants in criminal cases who themselves are victims of sexual exploitation or human trafficking.

Judges and court personnel in specialty court sessions are mindful of the constitutional due process rights of each participant and the importance of procedural justice to ensure trust and confidence in the court system. With the assistance of probation officers and behavioral health clinicians, the court closely monitors and reviews the availability and effectiveness of evidence-based treatment and encourages compliance with regular court reviews. Information regarding a participant’s treatment and compliance efforts is openly shared with the judge, defense, prosecution, probation, and specialty court staff.

E. Probation Violation Hearings (Intercept 3)

Probation violation and modification hearings present opportunities for mandating treatment for substance use disorders, mental health conditions, and co-occurring disorders. When a probationer is before the court after a finding of or admission to a probation violation, the court may order a new assessment, initial treatment, or intensified treatment as an alternative to revocation. A court has authority to modify conditions of probation in the absence of a violation. Modified or additional conditions must be reasonably related to the goals of sentencing and, if increasing the scope of the original probationary sentence, may not be so punitive as to significantly increase its severity. Commonwealth v. Santana, 489 Mass. 211, 223-224 (2022). The use of probationary sentences and the imposition of suspended sentences of different lengths, as recommended above, can provide judges with flexibility at the time of a violation hearing to apply gradually escalating responses for non-compliance. While sometimes it is necessary for the judge to revoke probation and sentence a defendant to incarceration to protect public safety, a court may not impose only part of a formerly suspended sentence as a means of coercion. G. L. c. 279, § 3; Commonwealth v. Holmgren, 421 Mass. 224 (1995).

Civil Commitments (G.L. c. 123)

A. Section 35

Upon the written application of certain petitioners (police officer, physician, spouse, blood relative, guardian or court official), the District, Juvenile, or Boston Municipal Court may hear a request for civil commitment of a person suffering from an alcohol use disorder[1] or substance use disorder.[2] G. L. c. 123, § 35. The judge may order a person committed for up to 90 days if the judge finds, by clear and convincing evidence, based on expert testimony and other evidence, that the respondent is an individual with an alcohol and/or substance use disorder and that there is a likelihood of serious harm because of the person’s alcohol and/or substance use disorder. Matter of G.P., 473 Mass. 112, 124-129 (2015); Uniform Trial Court Rules for Civil Commitment Proceedings for Alcohol and Substance Use Disorders G. L. c. 123, § 35 (2016). Civil commitments may occur independent of, or at any time during, the pendency of a criminal case.

A judge must consider less restrictive alternatives to commitment and the availability of treatment within the facility, and make findings, orally or in writing, in all civil commitment hearings. Matter of a Minor, 484 Mass. 295, 308-310 (2020).; see Foster v. Commissioner of Correction (No. 1), 484 Mass. 698, 726-728 (2020). The law is intended as an emergency measure for providing care and treatment “to promote the health and safety of the individual committed and others, as demonstrated by the statutory requirement that a committed individual pose a danger to him- or herself, or a member of the community.” Id. at 727; see Matter of G.P., 473 Mass. at 113, 121 n.15 (discussing emergency nature of § 35 proceedings). Commitment is not a long-term solution to alcohol and/or substance use disorders.

DPH and the Department of Correction determine suitable facilities for commitment purposes pursuant to G. L. c. 123, § 35. “The department of public health shall maintain a roster of public and private facilities available, together with the number of beds currently available and the level of security at each facility, for the case and treatment of an alcohol use disorder and substance use disorder and shall make the roster available to the trial court.” G. L. c. 123, § 35.

When a respondent presents with co-occurring symptoms of an alcohol and/or substance use disorder and a mental health condition, the court, with input from the court clinic, will decide the appropriate way to proceed that best meets the needs of the respondent (see § 12 commitments below). The court should provide persons who come to court looking for help with a family member with a substance use problem with information about community treatment resources and about filing a petition for a § 35 commitment, including the Frequently Asked Questions pamphlet. As § 35 does not permit self-petitions, a probation officer may petition on behalf of the person seeking commitment provided the person is known to Probation. If the person is not known to MPS, an otherwise eligible petitioner will need to file.

B. Section 12

The admission of an individual to a general or psychiatric hospital for psychiatric evaluation is governed by G. L. c. 123, § 12. Section 12(a) allows for an individual to be brought to a hospital for evaluation involuntarily for up to three days. The transport to the facility, initial psychiatric evaluation, and the admission for up to three days are commonly referred to as being “Section 12’d” or “pink papered” because the form may be printed on pink paper.

Pursuant to Section 12(a), certain persons (a physician, qualified advanced practice registered nurse, qualified psychologist, licensed independent clinical social worker, or, if those persons are not available, a police officer) may apply to admit anyone to a facility if they believe that the failure to hospitalize the person would create a likelihood of serious harm by reason of mental illness.

Admissions to a psychiatric facility can also be court-ordered pursuant to Section 12(e). That section allows anyone to apply to a District, Boston Municipal, or Juvenile Court for a three-day commitment of a person thought to be mentally ill whom the failure to confine would cause a likelihood of serious harm. The court must immediately appoint counsel for the person. After hearing, the court may issue a warrant for apprehension and appearance authorizing the police to apprehend the alleged mentally ill person if, in the court’s judgment, such action is necessary. Upon apprehension, the person will be brought to the court to be examined by a designated physician, a qualified psychologist, or a qualified advanced practice registered nurse designated to have the authority to admit to a facility. The statute allows for commitment for up to three days based solely on the court clinician’s finding that the failure to hospitalize the person would create a likelihood of serious harm by reason of mental illness. Due process requires a hearing and sufficient finding to order a three-day commitment for the purpose of further evaluation and treatment. G. L. c. 123, § 12(e).

Juvenile Court

A. Delinquency and Youthful Offender Matters

In delinquency and youthful offender cases, a judge may order substance use assessment, monitoring, and treatment as a condition of probation for a juvenile adjudicated delinquent or a youthful offender. G. L. c. 119, § 58. Conditions requiring substance use assessment, monitoring, and treatment may be ordered even before adjudication as part of the juvenile’s pretrial conditions of release (with the juvenile’s consent) or where the juvenile is placed on pretrial probation as a disposition (with the juvenile and the Commonwealth’s consent). G. L. c. 276, § 87; G. L. c. 276A; Commonwealth v. Preston P., 483 Mass. 759, 762 (2020). In the Juvenile Court, diagnostic studies or assessments are often referred to as evaluations. This language is used interchangeably below.

Treatment conditions can also be imposed prior to adjudication, even pre-arraignment, through diversion pursuant to G. L. c. 119, § 54A, and G. L. c. 276A. District Attorney’s Offices also provide diversion programs which often include an assessment of a youth’s mental health or substance use and related treatment.

If a judge commits a juvenile who has been adjudicated delinquent or as a youthful offender to the custody of the Department of Youth Services (DYS), DYS is responsible for assessing and determining whether the youth would benefit from substance use treatment. In such cases, the court should make specific information available to DYS regarding any substance use concerns.

DYS does not provide individual substance use treatment to youth committed to its care pre-adjudication or pre-disposition of a probation violation. If a youth before the court at this stage needs acute substance use treatment, the court may consider use of the § 35 process or otherwise access services through the Bureau of Substance Addiction Services (BSAS). Likewise, if a youth presents in court under the influence or is currently detoxing, the court should arrange for immediate medical attention. If a youth presents in court under the influence or is currently detoxing and is ordered detained, the court, not DYS, is responsible for transporting the youth to the hospital. DYS assumes supervision of a detained youth who is being treated at the hospital as soon as is reasonably possible. DYS remains responsible for supervision until such time that a youth can be safely discharged to the care or custody of DYS. The sheriff’s department is responsible for the transportation of detained youths.

Diagnostic assessments are also available pursuant to G. L. c. 119, § 68A, and can be conducted by DYS, the court clinic, or DMH. These assessments can be ordered both pre- and post-adjudication and are often used in the context of probation violation proceedings. Judges can order aid in sentencing evaluations pursuant to G. L. c. 123, § 15(e). Finally, prior to disposition of a youthful offender case, the court is required to order a pre-sentence investigation report from MPS. G. L. c. 119, § 58.

Unique to Massachusetts, each Juvenile Court is served by a Juvenile Court Clinic administered by DMH Forensic Services and funded as a partnership between DMH and the Administrative Office of the Juvenile Court (AOJC). The Juvenile Court Clinics consist of specially trained and certified licensed mental health professionals who primarily conduct court-ordered evaluations. In delinquency and youthful offender cases, there may be critical forensic questions regarding competence to stand trial, criminal responsibility for the charges, and assistance to the court in the development of appropriate dispositions.

Many youths in the juvenile justice system have behavioral health disorders and lack the resources to address them. Clinical input may be desired to help the court determine what alternative treatment or management options are most appropriate.

B. Child Requiring Assistance

In Child Requiring Assistance (CRA) cases, which include runaways, truants, habitual school offenders, and stubborn children, the court’s ability to order substance use treatment for a child is dependent upon the child’s custody status. For example, when a child is placed in the custody of the Department of Children and Families (DCF), the Juvenile Court may only request or recommend that substance use treatment be provided for the child. If the child remains in the parents’ custody, the Juvenile Court may order substance use treatment for the child as a condition of custody or as part of a dispositional order issued pursuant to G. L. c. 119, § 39H, allowing the child to remain in the parents’ custody.

Pursuant to G. L. c. 119, § 39G, court clinic evaluations are available pre- and post-fact finding. These evaluations are invaluable diagnostic assessments and contain extensive history with recommendations for both family and child.

C. Care and Protection

Care and protection cases present a strategic opportunity for court intervention with parents suffering from substance use disorders, keeping in mind the best interests of the children. G. L. c. 119, § 51A et seq. If the Juvenile Court judge believes substance use may be a factor, the judge should advise the respondent parent(s)/guardian(s) that failure to comply with substance use treatment will be considered as a factor in making the ultimate determination of parental unfitness or of termination of parental rights. However, the fact that the judge did not advise the parent(s)/guardian of the ramifications of failure to comply with substance use treatment does not prevent the judge from considering substance use as it affects parental abuse or neglect, in making an ultimate determination of parental unfitness or termination of parental rights.

If available, court clinic evaluations should be utilized early in care and protection cases, to provide the court with individualized assessments that can assist with custody and case tracking decisions. Early assessment and identification of appropriate treatment will promote the Juvenile Court goals of achieving permanency for children and families.

Probate and Family Court

The Probate and Family Court often hears cases where a party has a substance use disorder, mental health condition or both. These cases may involve divorce or paternity-related custody or parenting time disputes under G. L. c. 208 and c. 209C; petitions to dispense with parents' rights to consent to adoption under G. L. c. 210, § 3; guardianships of minors and adults under G. L. c. 190B; and applications for orders of protection under G. L. c. 209A.

The resources available to judges in the Probate and Family Court when presented with these issues are many. In a pending case, either a party, a probation officer or other interested person can best inform the judge of substance use or mental health issues. The judge may appoint a guardian ad litem to investigate and submit a report to the court. As part of that report, a qualified guardian ad litem can assess the validity and severity of allegations involving a substance use disorder, mental health condition or both and make recommendations to the court. The judge may also order a party to submit to a mental health examination. “In order to determine the mental condition of any party or witness before any court of the commonwealth, the presiding judge may, in [the judge’s] discretion, request the department [of mental health] to assign a qualified physician or psychologist, who, if assigned shall make such examinations as the judge may deem necessary.” G. L. c. 123, § 19; see also Mass. R. Dom. Rel. 35 (a).

Absent specific statutory or common law authority, Probate and Family Court judges have inherent authority to make orders related to the treatment of substance use disorders, mental health conditions, and co-occurring disorders,when it is in the best interests of a person under the court’s jurisdiction. “[A] probate court possesses broad and flexible inherent powers essential to the court’s duty to act in the best interests of persons under its jurisdiction.” Bower v. Bournay-Bower, 469 Mass. 690, 698 (2014); see also Matter of Moe, 385 Mass. 555, 561 (1982) (stating that the court’s inherent authority “extend[s] to actions necessary to afford any relief in the best interests of a person under [its] jurisdiction”). The court also has “certain inherent powers whose exercise is ‘essential to the function of the judicial department, to the maintenance of its authority, or to its capacity to decide cases.’” Bower, 469 Mass. at 698, quoting Sheriff of Middlesex County v. Commissioner of Correction, 383 Mass. 631, 636 (1981). It is important to note, however, that judges may not delegate decision-making authority to a treatment provider. See, e.g., Bower, 469 Mass. at 707, citing Silverman v. Spiro, 438 Mass. 725, 736-737 (2003).

A. Cases Involving Children

Many children are living in households with at least one parent who has a substance use disorder or a mental health condition, placing those children at increased risk for maltreatment. It is important for judges to recognize that children may experience trauma due to parental neglect, the results of their own prenatal substance exposure, chaotic environments, or removal from a parent’s home. Judges should also be aware of the stigma these children may be experiencing.

Judges should consider the direct service needs of children, which may include treatment with a trauma-informed professional and family therapy, with special consideration given to multigenerational trauma. Programs for parents that address parenting issues as part of recovery help reduce the negative effects on children. It is also critically important for children and their caregivers to understand that substance use disorder and mental health conditions are treatable.

In cases involving children, the judge should (1) identify substance use disorders, mental health conditions, and co-occurring disorders early in the case; (2) refer the parent to a trained clinician for a diagnostic assessment and to design an appropriate level of treatment, including medication-based treatment and recovery coaching; (3) monitor the parent's progress in treatment through interim hearings; and (4) manage the case by bringing it back periodically to determine progress and adjusting parenting time accordingly. A parent is likely to be receptive to treatment where that can result in reunification with a child.

B. Ordering Treatment in Custody and Parenting Time Disputes

Probate and Family Court judges have authority to attach conditions to parenting time sufficient to ensure the safety of a child. See, e.g., Schechter v. Schechter, 88 Mass. App. Ct. 239, 247-248 (2015). Sufficient evidence of substance use disorders, mental health conditions, or co-occurring disorders may influence custody and parenting time decisions. Permissible conditions likely include requiring a parent to pass a drug test, be evaluated for a substance use disorder, or attend treatment for substance use or mental health conditions. See Silverman, 438 Mass. at 729 n.2, 736-737 (upholding order requiring mother's participation in therapy as condition of visitation with her children, subject to judge's further reexamination in light of mother's progress).

Evidence of substance use disorders or mental health conditions, in the absence of any evidence of harm to the child, does not constitute parental unfitness. See Adoption of Katharine, 42 Mass. App. Ct. 25 (1997); see also Care and Protection of Bruce, 44 Mass. App. Ct. 758 (1998). Consequently, it is necessary to determine the connection between the disorder and the impact on parenting and the child’s functioning.

In chapter 209A proceedings, when granting parenting time to an abusive parent, Probate and Family Court judges may order the abusive parent “to abstain from possession or consumption of alcohol or controlled substances during the visitation and for 24 hours preceding visitation” and may “impos[e] any other condition that is deemed necessary to provide for the safety and well-being of the child and the safety of the abused parent.” See G. L. c. 209A, § 3.

Housing Court

The Housing Court generally hears summary process (eviction) cases, housing-related small claims cases and civil actions (e.g., breach of contract claims, housing discrimination, property damage, etc.), code enforcement actions, and appeals of local zoning board decisions that affect residential housing. The Housing Court has jurisdiction over civil and criminal matters that affect the health, safety, and welfare of occupants and owners of residential housing.

Summary process is the Housing Court’s largest volume of cases. Summary process was created to expedite the ability to recover possession of land. See, e.g., Bank of New York v. Bailey, 460 Mass. 327, 334 (2011), quoting Rule 1 of the Uniform Summary Process Rules (recognizing that the legislative purpose of eviction proceedings is to provide “‘just, speedy and inexpensive’ resolution of summary process cases”).

The recognized legislative purpose of summary process is consistent with the general mission of the Trial Court – to deliver justice with dignity and speed – but poses an additional challenge to administering justice in cases involving litigants with substance use disorders, mental health conditions, and co-occurring disorders. In most cases, balancing due process with the needs of litigants with substance use disorders, mental health conditions, and co-occurring disorders often requires slowing down the court process, especially because most litigants in the Housing Court are self-represented. As such, there is an inherent dichotomy in the Housing Court. While it is important to allow litigants with substance use disorders, mental health conditions, and co-occurring disorders time to access resources and develop accommodation plans due to the complex and chronic nature of those conditions (see Principles page 5), it is also critical to adhere to the legislative purpose of summary process by ensuring that cases move expeditiously.

Courts should recognize that self-represented litigants with substance use disorders, mental health conditions, and co-occurring disorders may face certain challenges, such as understanding the relevant law, seeking appropriate treatment, and raising disability-related protections or accommodations that may be available to them under the law. Further, it is imperative that courts recognize that individuals with substance use disorders, mental health conditions, and co-occurring disorders face greater barriers to recovery and access to treatment when they lack stable housing. As a result, courts should make efforts to maintain housing stability for individuals with substance use disorders, mental health conditions, and co-occurring disorders whenever possible, consistent with law.

Pursuant to the Supreme Judicial Court Code of Judicial Conduct, judges may, for example, exercise discretion and make referrals as appropriate to any resources available to assist the litigants, while being careful not to give any litigant an unfair advantage or create an appearance of judicial partiality. See S.J.C. Rule 3:09, Code of Judicial Conduct, Canon 2, Rule 2.6, and Comment 1A. In Housing Court, those resources currently include the Tenancy Preservation Program (“TPP”) which is available to those who meet eligibility requirements. TPP is a homelessness prevention program with the goals of identifying whether a tenant suffers from a disability, determining whether the disability can be reasonably accommodated and, if it can be, whether the tenancy can be preserved. In order to access TPP, tenants must be referred to the program by a judge and both parties must be willing to participate. Additionally, the volunteer “Lawyer for a Day” program may be available to those who are unrepresented and meet eligibility requirements, and the court should make all parties aware of the program and how to access it.

Finally, in appropriate circumstances, courts also should consider whether the appointment of a guardian ad litem would help the court to learn the limitations of the self-represented litigant. When necessary, the court may require an evaluation by a court clinician to determine whether such appointment, or other intervention, is needed or recommended. See G. L. c. 123, § 19.

Contact

Online

Phone

Maura A. Looney, Esq., Clerk

Allison S. Cartwright, Esq., Clerk

Jennifer Donahue, Public Information Officer

Address

| Last updated: | November 16, 2023 |

|---|