- Scientific name: Perimyotis subflavus

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Tricolored bat (Perimyotis subflavus)

The tricolored bat is a small bat with fur that varies in color but is most commonly yellowish or reddish brown above and paler below. This small bat has uniquely tricolored fur; the hairs of its back are slate gray at the base, yellowish brown in the middle, and dark brown at the tips. On its underside, the fur is a uniform yellowish brown. The tragus is straight with a blunt rounded tip and the calcar has no obvious keel. The skin covering the forearms is distinctly reddish and the top of the patagium (tail membrane) is well furred. Adult tricolored bats average 85 mm (3.3 in) in total length, and the forearm is 31-34 mm (1.2 to 1.3 in). This bat can also be identified by its weak, fluttery, erratic flight, which has given it the nickname “moth bat.”

Similar species: The tricolored bat, formerly called the eastern pipistrelle, can be most easily distinguished from other species found in Massachusetts by their reddish forearms, well-furred patagium and curved posture when roosting. This is the only species of bat in the Northeast with 34 teeth. All the species of Myotis have 38, while the big brown bat and all the tree bats have 32.

Life cycle and behavior

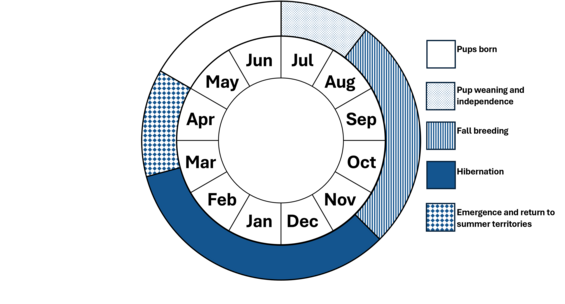

Tricolored bats are the earliest to emerge to feed in the evening. They use echolocation to locate insects, often catching them in tail or wing membranes. Their foraging area is small relative to other bats, but they may travel up to 8 km (5 mi) from their roosting site to feed. In late summer, the bats begin to “swarm” around the entrances of caves and are thought to be testing the air of potential hibernacula. Tricolored bats have been known to migrate up to 136 km (85 mi) to hibernation sites.

Tricolored bats are the first species to enter hibernation in the fall and the last to leave in the spring. During hibernation, their metabolisms slow and they enter torpor. Tricolored bats will rouse infrequently throughout the winter to drink water or move between spots within a cave. These bats typically hang singly from walls (not ceilings) in warmer sections of a cave or mine where the humidity is so high that water droplets often cover their fur. Individuals may occupy the same location in a cave for consecutive winters; usually an individual will have several spots to hang within a cave and will shift from spot to spot. In the spring, females awaken and leave caves earlier than males; some males may remain in caves until June.

Female bats congregate and tend to remain separate from males, except during breeding. Breeding occurs in the fall during swarming, and inactive sperm are believed to be stored by the females until spring, when eggs are fertilized. Females bear two young in late June to mid-July. The young are carried by their mother for the first few days of life and later left at the roosting site while she feeds. Young bats make their first flight before three weeks of age. The longevity record for the tricolored bat is over 14 years.

Population status

The tricolored bat listed as endangered under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act. Their numbers were reduced by heavy pesticide use in the mid-1900s but were steadily on the rise again until the outbreak of white-nose syndrome in the winter of 2007-2008. While they were once the third most abundant bat in Massachusetts caves, and were found in all the large hibernacula, they were never found in large numbers. The small populations of tri-colored bats that used infected hibernacula in the northeast experienced catastrophic losses averaging at least 90%. White-nose syndrome is caused by Pseudogymnoascus destructans, a species that was new to science, but closely related to other fungi that naturally grow in caves. This fungus appears to have been accidentally transported to a cave in New York from Europe where cave bats had long co-existed with the fungus and had developed immunity. In North America, the fungus grows over bats while they hibernate, causing them to frequently rouse from dormancy, losing valuable stored fat, and failing to survive the winter. The fungus is believed to be passed from cave to cave primarily by the movements of breeding male bats, but human transport is also thought to be responsible for the infection spreading to some hibernacula.

Distribution and abundance

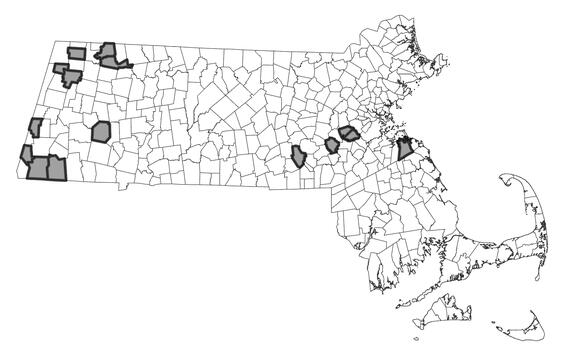

The tricolored bat is found across the eastern United States, from Maine south to central Florida, and west to Minnesota and Texas. It occurs north into the eastern provinces of Canada, and south through much of eastern Mexico into Honduras. In Massachusetts, these bats are believed to occur statewide and have been documented in 29 of 351 municipalities in 9 of 14 counties.

Distribution in Massachusetts from 1999-2024 based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

During the warmer months, tricolored bats occupy day and night roosts in forest vegetation in the canopy, most typically in dead leaves on mature live or recently dead deciduous trees. Maternity colonies, where females rear young, are commonly found among the dead needles of living pines. Colonies and roost sites are also occasionally situated in barns, out buildings, and other man-made structures, as well as in caves. Tricolored bats forage at the treetop level, in partly open country with large trees, over water courses, and at forest-field edges. They avoid deep woods and open fields. In winter, tricolored bats hibernate in limestone caves and abandoned mines. Winter hibernacula (hibernation sites) have been reported in Berkshire, Franklin, and Hampden counties.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

The greatest known threat to tricolored bats in Massachusetts is the white-nose syndrome. Summer habitat availability is not a limiting factor in Massachusetts.

Conservation

The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service is working in concert with government and non-profit groups to understand the spread of the fungus and potential for stopping its spread. Access to suitable, undisturbed hibernacula is essential to the survival of the tricolored bat, and protection of known sites is paramount. Human disturbance of hibernacula can be discouraged or prevented with the use of gated entrances, in order to avoid arousal of hibernating bats and the spread of fungal spores.

In Massachusetts, all listed species are protected from killing, collecting, possessing, or sale and from activities that would destroy habitat and thus directly or indirectly cause mortality or disrupt critical behaviors. In addition, listed animals are specifically protected from activities that disrupt nesting, breeding, feeding, or migration.

References

MassWildlife. 2020. Homeowner’s Guide to Bats. Massachusetts Department of Fisheries & Wildlife: Westborough, MA. 26 pp.

Perry, R.W., and R.E. Thill. 2007. Tree roosting by male and female Eastern Pipistrelles in a forested landscape. Journal of Mammalogy 88(4): 974-981.

U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service. 2012. “White-nose Syndrome.”

Whitaker, J.O., Jr. and W.J. Hamilton, Jr. 1998. Mammals of the Eastern United States, Third Edition. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY. 583 pp.

Contact

| Date published: | March 4, 2025 |

|---|