- Scientific name: Bartramia longicauda

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Endangered (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Upland sandpiper

The upland sandpiper is a slender, moderate-size shorebird with a small head, large, shoe-button eye, short dark-brown bill, long, thin neck and relatively long tail. Legs are yellowish. It stands about 30 cm (12 in) tall and has a wingspan of 64 to 68 cm (25 to 27 in). The crown is dark brown with a pale buff crown stripe. The rump, upper tail and wings are much darker than the rest of the bird. Calls include a rapid “quip-ip-ip-ip” alarm call, and a long, drawn-out courtship call which has been described as a windy, whistly, “whiiip-whee-ee-oo.” The sexes are similar. This species often poses with its wings up raised when alighting on utility poles or fence posts.

Life cycle and behavior

The upland sandpiper returns to its breeding habitat in Massachusetts mid-April to early May. The birds arrive already paired and usually return to the same area year after year. Their courtship displays include circling flights by individual birds that last 5 to 15 minutes and reach as high as 305 m (1,000 ft) during which they give their “windy whistle” call. On the ground, the male will raise his tail and run at his mate stopping suddenly. The nest is a grass-lined depression on the ground. It is well concealed by arched grasses. Four, or occasionally three, eggs are laid at 26-hour intervals. The eggs are pinkish-buff with fine brown spots. Both sexes incubate the eggs beginning after the clutch is complete. Renesting may occur if the initial clutch is destroyed.

Incubating adults are well-concealed. The adults are secretive around the nest, approaching it from a distance by walking cautiously through the grass, head held low and squatting lower and lower. Unless flushed, the bird leaves the nest in the same manner. The chicks are downy and precocial at hatching and leave the nest very soon thereafter. One or both adults care for the chicks, watching for danger as the chicks catch insects and sleep. The young reach full size and adult plumage by the time they fledge at 32 to 34 days. After fledging, families and individuals begin to mix and form flocks. Upland sandpipers gather in increasingly large flocks in July and begin fall migration from Massachusetts in late July and August.

The upland sandpipers primarily pursue grasshoppers, crickets, weevils, beetles, ants, spiders, snails and earthworms on the ground. They chase the insects rapidly and even leap into the air in pursuit.

Population status

The upland sandpiper is classified as Endangered in Massachusetts. They were formerly somewhat common in large pasturelands across Massachusetts into the 1850s, but commercial shooting for food, coupled with a subsequent loss of appropriate habitat to land development and succession of open fields led to its current status as one of the rarest breeding grassland birds in the state. The upland sandpiper is experiencing population decline over much of its range, particularly in the Midwest and eastern United States.

Distribution and abundance

The Upland Sandpiper breeds from Maine to central Canada and Alaska, Maryland to Oklahoma and Colorado. It breeds locally in Massachusetts. It winters in similar habitats in South America, particularly on the pampas of northern Argentina and Uruguay.

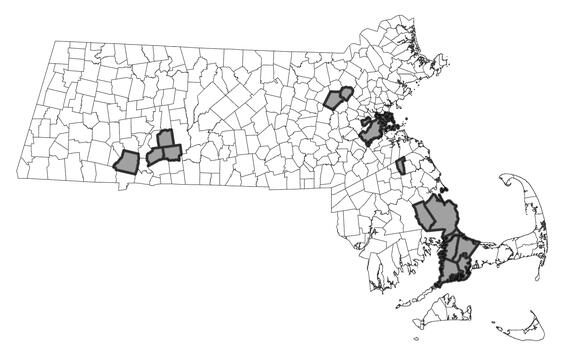

Distribution in Massachusetts. 1999-2024. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

Upland sandpipers nest primarily in sandplain grassland natural communities. Currently, many active breeding sites in Massachusetts are associated with airfields. Nesting habitat typically features large patches with high interior-to-edge ratios dominated by warm season bunch grasses (particularly little bluestem [Schizachyrium scoparium]) with interstitial areas of bare mineral soil and limited woody vegetation.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

The very large expanses of sandplain grassland habitat needed by breeding upland sandpipers is now very rare, and therefore, breeding occurrences of upland sandpipers have become very rare. The primary threat to upland sandpipers populations in Massachusetts is now habitat loss in the remaining breeding areas. Habitat loss occurs in two primary ways: direct habitat loss due to development, and indirect habitat loss due to the succession of sandplain grassland habitat to woody and generalist vegetation. Sandplain grasslands are a highly disturbance-dependent habitat, meaning that they need to experience regular appropriate disturbance events to maintain their integrity. Historically, this disturbance was often regularly occurring fire on the landscape. In the absence of fire, sandplain grassland will often shift to other unsuitable habitat types, such as grasslands dominated by turf grasses, meadows of clonal asters and goldenrods, shrublands or young forests. In situations where the habitat is maintained by regular mowing (like on airfields), mowing during the breeding often results in the destruction of breeding attempts.

Upland sandpiper

Conservation

Sandplain grassland habitat that has been degraded due to a lack of management can often be restored by controlling generalist vegetation, overseeding to little bluestem, and introducing a management regime that ideally includes prescribed fire. Upland sandpipers are excellent pioneers and will quickly find and recolonize restored habits, though the required large contiguous habitat patches of <100-acres result in very limited restoration opportunities in Massachusetts. In situations where upland sandpipers are present and prescribed fire is not currently feasible, mowing regimes should be adjusted to avoid the breeding season. However, dormant season mowing is generally not enough to prevent the eventual shift of sandplain grassland habitat to more generalist (and unsuitable) habitat, and so a more integrated management will be needed over the long-term.

Contact

| Date published: | April 3, 2025 |

|---|