- Scientific name: Pooecetes gramineus

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Threatened (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Vesper sparrow

The overall plumage pattern of the vesper sparrow is typical of many sparrow species with the head, back, tail, and wings covered by streaks of black, white, and a variety of browns. The upper chest has a series of evenly spaced, brown streaks that in some individuals may appear to form a v-shaped spot in the center of the chest. The under-tail and belly are usually cream-colored with no streaking. The vesper sparrow looks somewhat like a grayish song sparrow (Melospiza melodia), but with a thin, white eye-ring. The most distinguishing feature of the vesper sparrow is its white outer tail feathers (somewhat like those of the dark-eyed junco), which are particularly noticeable in flight. Another distinguishing feature is rufous- or chestnut-colored lesser wing coverts (shoulders), but they are seldom visible except, perhaps, in individuals with worn plumage. Vesper sparrows are larger than other New England grassland sparrows, with a length of 15.9 cm (6.25 in) and a wingspan of 25.4 cm (10 in). The song of the vesper sparrow is quite beautiful, similar in pattern to that of the song sparrow, but sweeter and more plaintive. The song typically begins with paired whistles followed by clear, musical trills that accelerate and descend in tone, described as too too tee tee chididididididid swiswi-swiswitteew. Generally, the first two introductory whistles are lower than the second two. In some cases, only a single higher whistle follows the first pair.

Life cycle and behavior

There are few published specific arrival and nesting dates in Massachusetts, but most vesper sparrows likely arrive in April and breed during May–August. The nest is constructed on the ground by the female, in a slight depression and at the base of vegetation (e.g., grass, forbs, shrubs). The nest is usually well-concealed but may occasionally be in the open. Outer materials consist of coarse and fine grasses, forbs, moss, rootlets, and bark; the inner cup is lined with finer grasses, hair, down feathers, or even pine needles.

Vesper sparrows are capable of producing up to 3 broods per year in some parts of the species’ range, but 1–2 broods are probably typical in Massachusetts. Clutch size is usually 3-5 eggs, with second clutches likely to have fewer eggs than first clutches. Nests are sometimes parasitized by brown-headed cowbirds (Molothrus ater). The eggs are variable in color and pattern, with a base color of white to greenish- or brownish-white, and speckles, spots, or blotches of brown, lavender, or purplish gray. The eggs are incubated for 11–14 days, mainly by the female. The young leave the nest at 9–13 days of age but are not then capable of sustained flight. They remain dependent on their parents for another 3 weeks and are fed a diet primarily of insects (e.g., grasshoppers, caterpillars). Adults consume both insects and seeds.

Population status

Vesper sparrow is listed as threatened in Massachusetts. Data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey (BBS) during the period 1966–2006 suggest that populations have been declining at an annual rate of 0.9% range wide and 3.1% in the eastern United States, with greater rates of decline during the first 15 years of the survey period.

Distribution and abundance

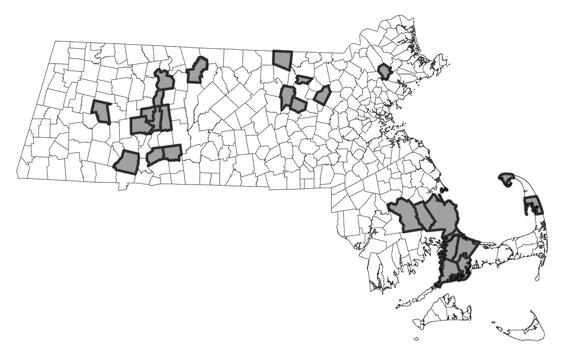

The vesper sparrow is a Nearctic (North American) breeder; the northern extent of its range is Nova Scotia west to interior British Columbia, and the southern extent of the range is western Virginia to southern Illinois, northern New Mexico, and southern California. However, most breeding populations occur in the western half of the range. Vesper sparrows overwinter throughout the lower U.S. and northern Mexico. In Massachusetts, vesper sparrows have been observed in Barnstable, Bristol, Essex, Franklin, Hampden, Hampshire, Middlesex, Plymouth, Suffolk and Worcester Counties. Most observations are from the Connecticut River Valley region and Barnstable County.

Distribution in Massachusetts. 1999-2024. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

The vesper sparrow is considered more of a habitat generalist than some of our other grassland sparrows because their territories often include taller woody vegetation interspersed within the grassland, rather than being completely open. Habitats of vesper sparrows are typically dry, well-drained sites with a mixture of short grass, bare ground, and shrubs, trees, or other high structures from which males can sing, including telephone lines and poles. However, vesper sparrows are not considered forest species as they are not typically affiliated with dense shrublands or post-logging forest regeneration. Habitats in Massachusetts consist of airfields, heathlands, bare area row crop fields, abandoned gravel pits, sandplain grasslands, coastal moors, and occasionally capped landfill.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

The primary acute threat to breeding populations of vesper sparrow in Massachusetts is habitat disruption during the breeding season, often due to mowing or tilling, which can result in destruction of nests and young. Long-term, loss of suitable breeding habitat due to development, agricultural abandonment, continuing fire suppression, and increasing forest succession is the primary limiting factor.

Predation by domestic cats has been identified as the largest source of mortality for wild birds in the United States with the number of estimated mortalities exceeding 2 billion annually. Cats are especially a threat to those species that nest on or near the ground.

An additional threat to the species is collisions with buildings and other structures, as approximately 1 billion birds in the United States are estimated to die annually from building collisions. A high percentage of these collisions occur during the migratory periods when birds fly long distances between their wintering and breeding grounds. Light pollution exacerbates this threat for nocturnal migrants as it can disrupt their navigational capabilities and lure them into urban areas, increasing the risk of collisions or exhaustion from circling lit structures or areas.

Conservation

Maintaining suitable habitat structure (large, open, sparsely vegetated landscapes) is the primary need for vesper sparrow in Massachusetts. In more natural settings, management with prescribed fire is the ideal tool, whenever possible. In more anthropogenic situations, avoiding tilling and mowing during the breeding season is important.

Promote responsible pet ownership that supports wildlife and pet health by keeping cats indoors and encouraging others to follow guidelines found at fishwildlife.org.

Bird collision mortalities can be minimized by making glass more visible to birds. This includes using bird-safe glass in new construction and retrofitting existing glass (e.g., screens, window decals) to make it bird-friendly and reducing artificial lighting around buildings (e.g., Lights Out Programs, utilizing down shielding lights) that attract birds during their nocturnal migration.

References

Baicich, P.J., and C.J.O. Harrison. A Guide to the Nests, Eggs, and Nestlings of North American Birds. 2nd ed. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 1997.

Jones, S.L., and J.E. Cornely. “vesper sparrow (Pooecetes gramineus).” 2002. The Birds of North America Online (A. Poole, Ed.). Ithaca: Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

Petersen, W.R., and W.R. Meservey. Massachusetts Breeding Bird Atlas. Amherst, MA: Massachusetts Audubon Society and University of Massachusetts Press, 2003.

Rising, J.D. The sparrows of the United States and Canada. San Diego, CA: Academic Press, 1996.

Sauer, J.R., J.E. Hines, and J. Fallon. The North American Breeding Bird Survey, Results and Analysis 1966 - 2006. Version 10.13.2007. Laurel, MD: USGS Patuxent Wildlife Research Center, 2007.

Sibley, D.A. The Sibley Guide to Birds. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 2000.

Contact

| Date published: | April 4, 2025 |

|---|