- Scientific name: Sorex palustris

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Special Concern (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Water shrew (Sorex palustris)

The water shrew is the largest long-tailed shrew in New England. It measures 144-158 mm (5.7-6.2 in) in length, with its long tail accounting for more than half of its total length and weighs from 10-16 g (approximately 0.33 oz). The unique feature of the water shrew is its big “feathered” hind foot. The third and fourth toes of the water shrew’s hind feet are slightly webbed, and all toes as well as the foot itself have conspicuous stiff hairs along the sides. Both the webbing and the fringe of hairs increase the water shrew’s swimming efficiency.

The male and female water shrew are colored alike, equal in size, and show slight seasonal color variation. In winter, the water shrew is glossy, dark gray black above tipped with silver, and silvery buff below, becoming lighter on the throat and chin. It has whitish hands and feet, and a long, bicolored (i.e., lighter beneath, darker above) tail covered with short, brown bristles. In summer, its pelage (fur) is more brownish above and slightly paler below, with a less frosted appearance. They molt in late May through early June and again in September. The color of immatures is much like that of adults. The water shrew is slender with a long, narrow snout that is highly movable and incessantly rotating. Its eyes are minute but visible, and its ears are small and hidden in velvety fur. Females have six mammae.

This species is especially adapted for semi-aquatic life. Not only are the large, webbed hind feet an adaptation for aquatic living, but the pelage of the water shrew is so dense that it is impenetrable by water and serves to trap air bubbles, retarding wetness and enhancing buoyancy. This trapped air also enables the water shrew to exhibit “water-walking” behavior. The water shrew can remain submerged for about 15 seconds but only while swimming vigorously. The air trapped in the fur makes it as buoyant as a cork. If it stops swimming, the little shrew will pop up to the surface like a beach ball. The water shrew depends upon its specialized hind feet as the major source of propulsion. The tail plays no part in swimming but may aid the animal in making quick turns while submerged.

Similar species: Five other species of shrews are found in Massachusetts: the masked shrew (Sorex cinereus), smoky shrew (Sorex fumeus), rock shrew (Sorex dispar), pygmy shrew (Sorex hoyi), and short-tailed shrew (Blarina brevicauda). The water shrew is distinguishable from all of these because it is the largest of the long-tailed shrews, and the only shrew that has long hairs along the margins of its hind feet.

Life cycle and behavior

The water shrew is secretive and elusive, seeking cover along the waterways. It lives in bankside burrows, the entrance often concealed deep between boulders or between the gnarled roots of a leaning streamside hemlock. Small surface runways are usually found under cover of bank overhangs, fallen logs, brush piles or other debris. The water shrew makes its own runways but also uses those of mice and moles. It is active throughout the year at any time of the day or night, with peaks of activity at sunrise and sunset. It has periods of deep slumber, but during its waking hours it is extremely active, foraging excitedly for short periods, darting rapidly over the ground, traveling through subsurface tunnels, or burrowing through snow.

The water shrew feeds primarily on aquatic insects, chiefly mayflies, caddis flies, stone flies, and other flies and beetles and their larvae, although snails, flatworms, small fish, and fish eggs are also eaten when available. Because the eyes of the water shrew are poorly developed, it uses its keen senses of touch, hearing, and smell when foraging. Foraging takes place both under and on top of the water. Prey is located underwater entirely by touch. The long whiskers located on either side of the shrew’s head are extended stiffly out to the sides while the animal is casting for prey. It is speculated that water vibrations from the intended victim may also aid in guiding the water shrew to its prey.

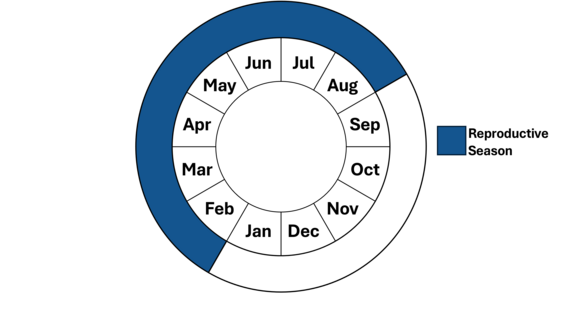

There have been few studies focused on the reproduction of the water shrew. From the available data, it is believed that male water shrews breed in their second spring, but in cases of low population density females have been known to breed in their first summer. Breeding activity usually begins in February and continues into August.

The nest of the water shrew is made from dried moss or other vegetation tucked away in a streamside burrow, rocky crevice, or among the tangled roots of wetland trees. A female may rear 2 or 3 litters in the course of one breeding season. Litter size ranges from 5 to 8, with 6 being most common. Gestation is approximately 21 days. The young are weaned in about 3 weeks and then drift away for a solitary life. The life span of the water shrew is approximately 18 months. The average shrew lives less than a year.

Population status

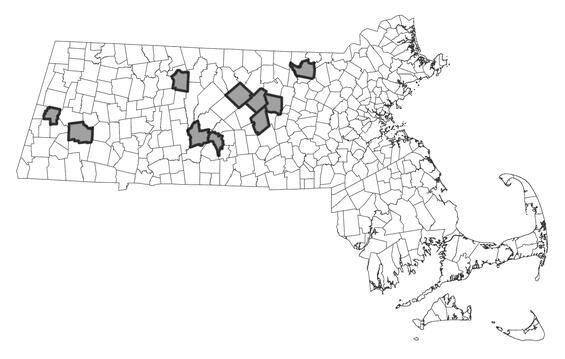

The water shrew is currently listed as a species of Special Concern in Massachusetts. It has rarely been observed in the state, but few deliberate searches for it have been made. Its reclusive habits make it difficult to encounter by chance; therefore, very little is known about its actual distribution and abundance in the state. The water shrew has been documented in 15 of the 351 municipalities in 7 of the 14 counties.

Distribution and abundance

The water shrew is found in the north temperate forest belt from isolated high mountain forest in the southern Appalachians of North Carolina and Tennessee, northward through New England into northern Quebec and Labrador. Water shrews farther west are now considered distinct species, including the northern water shrew (S. palustris), western water shrew (S. navigator), and Pacific water shrew (S. benderii).

Distribution in Massachusetts.

2000-2025

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

The water shrew is seldom found more than a few yards from the nearest water, most commonly the banks of a swift rocky stream usually near a conifer or mixed forest. It prefers heavily wooded areas and is rarely found in marshes that are devoid of bushes and trees. It may be found in beaver lodges and muskrat houses in winter.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

The primary threat to the water shrew is loss ofhabitat, specifically high-quality rocky streams bordered by forest.

Conservation

Directed surveys are needed to better identify the Massachusetts range of the water shrew and to locate occupied streams. The Massachusetts Wetlands Protection Act, and Endangered Species Act, working together, provide a first line of defense for Massachusetts populations of water shrew once they have been identified.

References

Beneski, J.T., Jr. and D.W. Stinson. 1987. Sorex palustris. Mammalian Species 296:1-6.

DeGraaf, R.M., and D.D. Rudis. 1986. New England Wildlife: Habitat, Natural History, and Distribution. General Technical Report NE-108. Broomall, Pennsylvania: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Northeastern Forest Experiment Station.

Godin, A.J. 1977. Wild Mammals of New England. Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins Press.

Merritt, J.F. 1987. Guide to the Mammals of Pennsylvania. Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania: University of Pittsburgh Press.

Contact

| Date published: | March 5, 2025 |

|---|