- Scientific name: Celastrus scandens L.

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Threatened (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

American bittersweet, Celastrus scandens, is a deciduous, woody vine in the staff-tree family (Celastraceae), known for its showy fruits in the fall and early winter. It reaches 6-9 m (20-30 ft) or more in height, with stems up to 10 cm (0.3 in) in diameter.

The leaves of American bittersweet are alternate, elliptical or ovate (5-8 cm [2-3.1 in] long; 3-5 cm [1.2-2 in] wide), yellowish-green, and pointed with serrate margins. The brown bark is initially smooth and turns corky and scaly as it matures. The inconspicuous, cup-shaped flowers are 2-3 mm (0.08-0.12 in) tall, greenish-yellow, and have five sepals. They appear in terminal clusters that are 3-8 cm (1.2-3.1 in) long, typically with 6 or more flowers per inflorescence. Spherical orange-yellow fruit capsules split open in the fall to reveal the waxy, red, fleshy arils that surround the seeds. The showy fruits and arils may persist through the winter.

American bittersweet is often confused with Oriental bittersweet (C. orbiculatus), an invasive species originating from northeast Asia. American bittersweet flowers are arranged in terminal clusters (panicles) and have yellow pollen, while Oriental bittersweet flowers are found in the leaf axils and have white pollen. American bittersweet leaves are also narrower than those of Oriental bittersweet, which are nearly round. The color of the ovary wall may also help to distinguish these species, though this is not always consistent. Oriental bittersweet capsules are usually yellow, and contrast sharply with the scarlet arils. American bittersweet capsules are dark orange, and less distinct from the arils. Another difference is the outer bud scales of Oriental bittersweet are keeled and angle out, whereas the ones on American bittersweet are not. American bittersweet is generally more restricted to open habitats and edges, whereas Oriental bittersweet is found in a variety of habitats and can tolerate a wider range of light conditions. These species may occur together on the same sites and intertwine. Hybrids of these species also occur in Massachusetts and are identified by a combination of characters typical of each of the parents (for example, leaves of one and fruit of the other), or by intermediate characters.

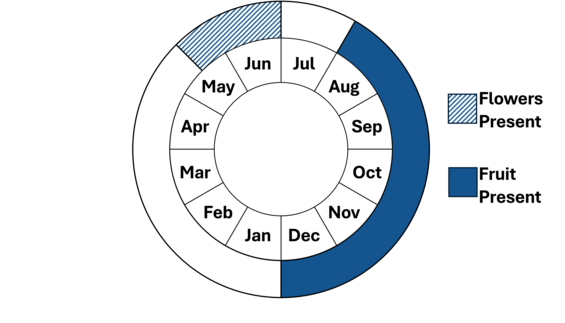

Life cycle and behavior

American bittersweet is generally dioecious, with functional male and female flowers on separate plants. Orange or red capsules open when mature to expose red arils that surround the seeds. The fruits are poisonous to humans but palatable to birds, which are the primary dispersers of the seeds.

Population status

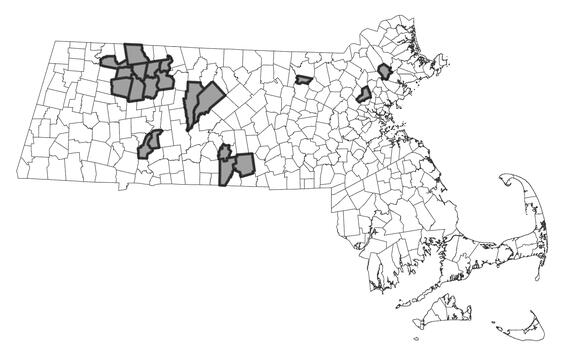

American bittersweet is listed under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act as Threatened. All listed species are protected from killing, collecting, possessing, or sale, and from activities that would destroy habitat and thus directly or indirectly cause mortality or disrupt critical behaviors. American bittersweet has 29 populations that have been verified since 1999 in Essex, Franklin, Hampden, Hampshire, Middlesex and Worcester counties. There are historical records from all counties in Massachusetts except Barnstable and Suffolk counties. Although there are a number of populations, only 4 populations appear to have potential long term viability through sufficient numbers and having both male and female plants.

Distribution and abundance

American bittersweet is known from Quebec south to Georgia and west to Saskatchewan and Texas. It is critically imperiled or imperiled in many southern and western states. In New England, it is critically imperiled in Rhode Island, imperiled in Connecticut and Massachusetts and vulnerable in Vermont. It has not been assessed in Maine or New Hampshire.

Distribution in Massachusetts

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database

Habitat

American bittersweet prefers open to patchy light conditions and is often found in woodland edges, thickets, roadsides, and rarely in the forest understory. This woody vine is a climber that can twine into the canopy foraging for light. Although this species was collected historically from a range of habitats, several recent records have been from rocky slopes and powerlines in areas with mafic bedrock.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

American bittersweet populations have declined in Massachusetts in recent decades. The fruit-laden branches are prized for use in fall and winter home decorations, and collecting for wreaths has reduced populations in some areas. The invasive Oriental bittersweet is more aggressive than American bittersweet and may displace the native species. Hybridization between the two species represents a significant threat to populations of American bittersweet. Misidentification may also result in American bittersweet removal through management intended to remove invasive species. The species in Massachusetts does not grow with the same robust vigor that it does in the mid-west. A recent discovery of a fungal infection on plants may be causing seasonal die offs.

Conservation and management

Survey for this species is needed. The best time to survey is when the plants are in bloom during June. Please report stems observed as ramets and include whether they are male (having only pollen bearing flowers) or female (only with stigmas or early fruit, no stamens). Populations should be monitored to determine whether exotic species are out-competing American bittersweet. Where needed, a plan should be developed, in consultation with MassWildlife’s Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP), to control competitors. All active management of rare plant populations (including invasive species removal) is subject to review under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act and should be planned in close coordination with NHESP. More research into potential causes of decline in the species is needed, including how prevalent fungal infections might be, and the source, and how can it be prevented.

References

Haines, A. 2011. Flora Novae Angliae – a Manual for the Identification of Native and Naturalized Higher Vascular Plants of New England. New England Wildflower Society, Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, CT.

Leicht-Young, S.A., J.A. Silander, and A.M. Latimer. 2007. Comparative performance of invasive and native Celastrus species across environmental gradients. Oecologia 154: 273–282.

Leicht, S.A., and J.A. Silander Jr. 2006. Differential responses of invasive Celastrus orbiculatus (Celastraceae) and native C. scandens to changes in light quality. American Journal of Botany 93: 972-977.

NatureServe. 2009. NatureServe Explorer: An online encyclopedia of life [web application]. Version 7.1. NatureServe, Arlington, VA. http://www.natureserve. org/explorer.

Contact

| Date published: | April 9, 2025 |

|---|