- Scientific name: Linnaea borealis L.

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Special Concern (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

Image credit: Marilee Lovit

American twinflower (Linnaea borealis) is a trailing, evergreen wildflower of the honeysuckle family (Caprifoliaceae), found in a variety of forest habitats across North America. Its scientific name honors Carl Linnaeus, “father of modern taxonomy,” and its common name refers to the distinctive paired pinkish flowers on each stalk and the opposite leaf arrangement along its creeping branches.

This “subshrub” grows via stolons along the forest floor. Its aerial branches can reach up to 10 cm (4 in) in height, with numerous pairs of oppositely arranged, coarsely toothed, oval leaves. These are about 1-2 cm (0.4-0.8 in) long. In late spring and summer, slender peduncles (flower stalks) grow from the aerial branches up to 10 cm (4 in) high, each bearing two nodding, five-lobed flowers. The petals are white to pink, 1-1.5 cm (0.4-0.6 in) long, forming a tube at the base and flaring at the tip. Fruits are 3 mm (0.12 in) in size, with three chambers (locules), but only one seed.

Linnaea borealis is the only species in its genus. Three subspecies occur in North America, but only L. borealis ssp. americana is indigenous to the Northeast. Subspecies longiflora (long-tube or Pacific twinflower) occurs mainly in the Pacific Northwest, and ssp. borealis is native to Alaska, Siberia, and northern Europe.

American twinflower may be confused with two other trailing plants in similar habitats: partridgeberry (Mitchella repens) and creeping wintergreen (Gaultheria hispidula). Partridgeberry has opposite evergreen leaves and paired, pale flowers, but its leaves have smooth (entire) margins, and the flowers are sessile, erect, and four-lobed. Creeping wintergreen differs with alternate leaves and also has entire margins and four-lobed sessile flowers.

Life cycle and behavior

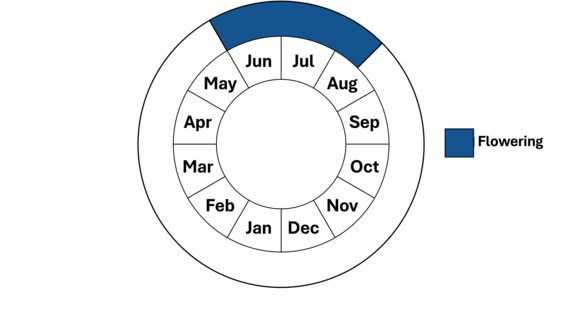

American twinflower is a perennial species that is trailing and evergreen. It flowers from early June through mid-August.

Population status

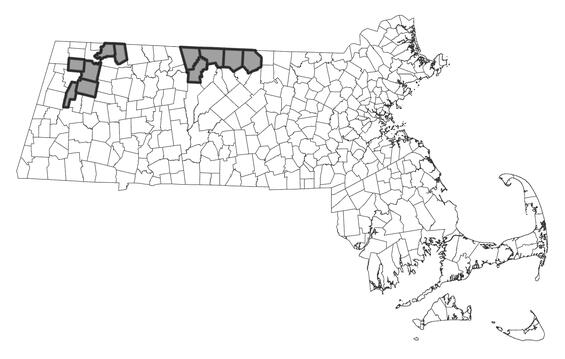

American twinflower is listed as special concern under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act. All listed species are protected from killing, collecting, possessing, or sale and from activities that would destroy habitat and thus directly or indirectly cause mortality or disrupt critical behaviors. There are 19 occurrences that have been verified since 1999 in Berkshire, Franklin and Worcester Counties.

Distribution and abundance

American twinflower is found in all Canadian provinces and territories, and in 30 U.S. states. It ranges across New England west to Washington, and south to Maryland, West Virginia, Tennessee, Indiana, Iowa, New Mexico, Arizona, and California. In the Northeast, it is common in northern New England and New York, rare in Connecticut and Massachusetts, and potentially extirpated from New Jersey and Rhode Island.

Distribution in Massachusetts. 2000-2025. Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database.

Habitat

American twinflower is typically associated with cool, moist, boreal forest habitats such as spruce-fir forests and high-elevation communities. In Massachusetts, it is primarily found in moist forests, edges, and wetlands with red spruce (Picea rubens), balsam fir (Abies balsamea), and northern hardwoods. It also occurs less frequently in drier forests with red pine (Pinus resinosa), white pine (P. strobus), and oaks (Quercus spp.). Common associates include eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis), birches (Betula spp.), American beech (Fagus grandifolia), blueberries (Vaccinium spp.), wintergreens (Gaultheria spp.), bunchberry (Chamaepericlymenum canadense), bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum), and mosses such as Sphagnum spp. and Polytrichum commune.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Threats

In Massachusetts, a major threat to American twinflower is the low viability of small populations due to its inability to successfully cross-pollinate with close relatives. Even when seeds are produced, they do not remain viable long in the seed bank. Although it spreads asexually via stolons, limited opportunities for sexual reproduction can make populations vulnerable to decline.

Habitat-related threats include roadside management, salt, and physical disturbances near off-road vehicle trails.

Conservation

While invasive species are not currently a documented threat to Massachusetts populations, monitoring for invasive encroachment is recommended. All management actions affecting state-listed plant populations, including invasive species removal, must be reviewed under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act and coordinated with the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP).

References

Gleason, Henry A., and Arthur Cronquist. Manual of Vascular Plants of Northeastern United States

and Adjacent Canada, Second Edition. Bronx, NY: The New York Botanical Garden, 1991.

Haines, A. 2011. Flora Novae Angliae – a Manual for the Identification of Native and Naturalized Higher Vascular Plants of New England. New England Wildflower Society, Yale Univ. Press, New Haven, CT.

NatureServe. 2025. NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. Accessed: 5/23/2025.

POWO (2025). Plants of the World Online. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet; https://powo.science.kew.org/ Accessed: 5/24/2025.

Seymour, Frank C. 1969. The Flora of New England, First edition. Charles E. Tuttle Company, Inc. Tokyo, Japan.

Contact

| Date published: | April 30, 2025 |

|---|