- Scientific name: Crepidomanes intricatum (Farrar) Ebihara & Weakley

- Species of Greatest Conservation Need (MA State Wildlife Action Plan)

- Special Concern (MA Endangered Species Act)

Description

A colony of Appalachian bristle-fern photographed in a rock crevice. Photo credit: Matthew Charpentier

Appalachian bristle-fern (Crepidomanes intricatum), a member of the largely tropical filmy fern family (Hymenophyllaceae), is an independent gametophyte that lives within crevices of rock outcrops. Made up of dense tangles of wiry filaments, this fern resembles steel wool, or a weaver’s woolly “weft.” It is thought that this fern has evolved to live perpetually within the gametophyte phase of the fern life cycle, never forming a sporophyte, the leafy spore-producing phase that is most familiar to us. Recall that in other local ferns, gametophytes, which are haploid, thumbnail-sized, and heart-shaped, grow in hospitable habitats from spores released by the fern’s fertile fronds; male and female sex organs (antheridia and archegonia, respectively) form within the gametophyte and release gametes (sex cells). The leafy diploid sporophyte results from fertilization. This “alternation of generations” does not occur in Appalachian bristle-fern; the gametophyte, which is filamentous, not heart-shaped, has apparently lost its ability to produce gametes. Instead, it reproduces asexually by releasing small buds called “gemmae,” which are made up of two to ten cells, and are borne on stalks called “gemmifers.”

Other members of the filmy fern family are known from wet tropical regions of the world; named for their characteristically thin fronds, the species of this family require moist conditions to keep from desiccating. Research has shown that even under tropical conditions, Appalachian bristle-fern gametophytes are unable to produce gametes, indicating the species is genetically incapable of sexual reproduction. One hypothesis for the origin of this species in the Northeast is that it is a relic from the Tertiary Period (2 to 65 million years ago), in which tropical forests covered this region. As the climate cooled, fern gametophytes may have adapted, persisting in stable, rocky habitats, and eventually becoming completely asexual.

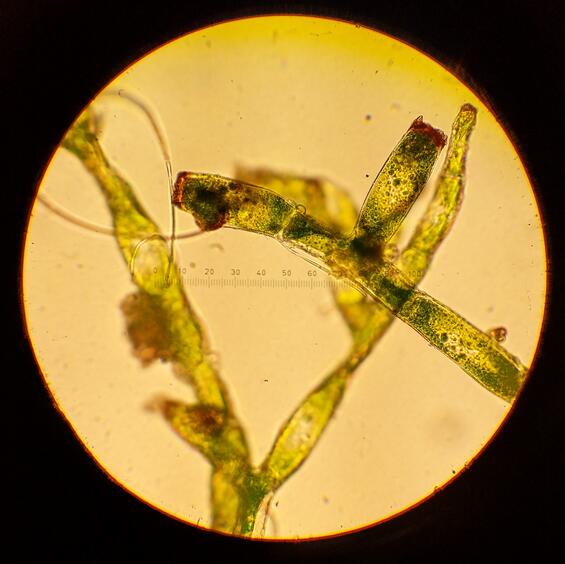

The filaments of Appalachian bristle-fern are a single cell thick. When desiccated its chloroplasts shift to the edges of each cell, leaving a transparent center, and giving the filaments a chain-like appearance. Appalachian bristle-fern’s stature and cryptic nature requires detailed observation, under 20x magnification or greater, to document the presence of rhizoids, gemmae, and gemmifer cells, which distinguish it from co-occurring algae and bryophyte protonemata.

A specimen of Appalachian bristle-fern under magnification depicting gemmifer cells. Photo credit: Matthew Charpentier

A specimen of Appalachian bristle-fern under magnification depicting rhizoids. Photo credit: Matthew Charpentier

Life cycle and behavior

Appalachian bristle-fern grows in tufts less than 1 sq cm (0.155 sq in) to over 1 sq m (10.76 sq ft) in size. Reproduction is achieved through asexual means using gemmae. It is unknown how these gemmae spread to new habitats.

Population status

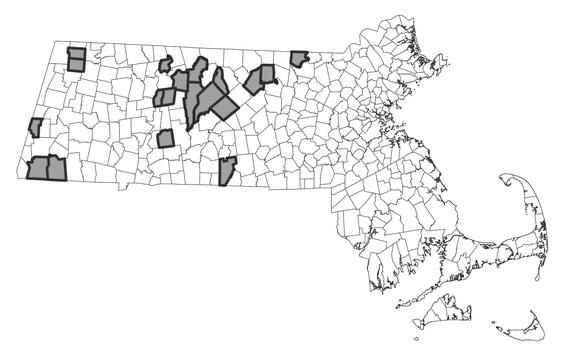

Appalachian bristle-fern has recently been downgraded from endangered to special concern under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act due to an increase in the number of known populations. Appalachian bristle-fern currently has 29 known populations in Berkshire, Franklin, Hampden, Hampshire, Middlesex and Worcester Counties that have been observed in the last 25 years and reported to the Natural Heritage and Endangered Species Program. Given Appalachian bristle-fern’s diminutive size and often difficult to access habitat, it is probable that additional unrecorded populations exist in suitable habitats.

The number of known populations of Appalachian bristle-fern in Massachusetts has significantly increased in recent years, from 10 known stations in 2012 to the current 29 known stations. The additional 19 stations were all found between 2018 and present. Many of these populations encompass small areas around 1 sq cm, however, it is difficult to fully assess the size of populations because the habitat of this species can be difficult to access and thoroughly survey. If you see any rare species, please report them through Heritage Hub.

Distribution and abundance

Appalachian bristle-fern occurs throughout the east coast of North America from Alabama to Quebec (NatureServe Explorer, Charpentier and Green 2019). It is of conservation concern in several states, including vulnerable in Massachusetts, Kentucky, North Carolina, and Vermont; imperiled in Georgia; and critically imperiled in Indiana, New York, South Carolina, and New Jersey.

Distribution in Massachusetts

1999-2024

Based on records in the Natural Heritage Database

Habitat

Appalachian bristle-fern inhabits cool, dark, crevices, cracks, and pockets, typically within circumneutral or rich rocky outcrops. The gametophytes are often two or more feet deep within a crevice and require a flashlight to observe but can occupy more shallow depressions. In Massachusetts, most of the known sites are shady and moist, often with eastern hemlock (Tsuga canadensis) in the canopy shading the crevices. Additional associated plant species occurring near the rock crevice include maidenhair spleenwort (Asplenium trichomanes), marginal wood-fern (Dryopteris marginalis), bulblet-fern (Cystopteris bulbifera), and sugar maple (Acer saccharum). Bryophyte cover ranges from very dense to very sparse. Aspect varies, but many known sites on east-facing outcrops. The type of bedrock also varies but tends to be circumneutral to high pH, and the species seems to be absent from the most acidic outcrops. Though literature specifies that habitat is typically not calcareous, there are several known populations in Massachusetts growing on marble.

Healthy habitats are vital for supporting native wildlife and plants. Explore habitats and learn about conservation and restoration in Massachusetts.

Appalachian bristle-fern habitat, note that hand is pointing to the location in the rock feature where Appalachian bristle-fern was observed. Photo credit: Matthew Charpentier

Threats

Threats include anything that could change the dark, moist, cool environment favored by this gametophyte. Appalachian bristle-fern lives in one of the most stable natural habitat types in the Northeast, and there are relatively few threats beyond development involving rock blasting. A more subtle threat is a loss of shading canopy cover due to tree removal or death. Hemlock woolly adelgid and hemlock scale are damaging trees in at least two known Appalachian bristle-fern locations. Increases in sun exposure could change the microclimate (e.g., light, temperature, moisture), resulting in an inhospitable environment. As this plant does not seem to spread very rapidly, abrupt changes may be more detrimental than those that take place over a long period of time.

Anthropogenic threats to Appalachian bristle-fern may include quarrying or mining operations; clear-cutting, which could alter substrate surface temperatures and moisture; or recreational caving during which people may inadvertently rub Appalachian bristle-fern off the substrate surface. Additionally, habitat fragmentation may limit the capacity for Appalachian bristle-fern to recruit to new sites.

Conservation

Survey and monitoring

The small number of known populations of Appalachian bristle-fern may be an underestimate of its true distribution, due to its small size, unusual morphology, and difficult to access habitat. Additional unrecorded populations of Appalachian bristle-fern may be present within suitable habitats in the state. Surveys for this species are needed. It is helpful to survey first with someone familiar with the population before searching on your own. A flashlight is required to identify Appalachian bristle-fern growing in its natural habitat, as is a 15 -20x lens. Appalachian bristle-fern can be identified all year so long as suitable habitat is not covered in ice or snow. In addition, it becomes difficult to identify when wet after a rainstorm.

Management

All active management of rare plant populations (including invasive species removal) is subject to review under the Massachusetts Endangered Species Act and should be planned in close consultation with the Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program. The primary management needs of this plant are to maintain the canopy species that shade the crevices in which this species grows.

Research needs

Appalachian bristle-fern is believed to be a single genetically identical individual that has spread. Related species in the Hymenophyllaceae have similar filamentous gametophytes. Genetic analysis of Appalachian bristle-fern in Massachusetts (and other states) could help to determine whether populations are distinct.

Acknowledgements

MassWildlife acknowledges the expertise of Matt Charpentier who contributed substantially to the development of this fact sheet.

References

Charpentier, Matthew P. and Laura Green. Habitat characterization and assessment of the northern range limit of the regionally rare Crepidomanes intricatum in Northeast North America. Nov. 30, 2019. Rhodora.org. https://www.rhodora.org/awards/mehrhoff/Mehrhoff-Report-Charpentier-Green-2019.pdf

NatureServe. 2025. NatureServe Network Biodiversity Location Data accessed through NatureServe Explorer [web application]. NatureServe, Arlington, Virginia. Available https://explorer.natureserve.org/. Accessed: 3/14/2025.

Sessa, Emily B. 2024. Ferns, Spikemosses, Clubmosses, and Quillworts of Eastern North America. Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ.

Contact

| Date published: | April 10, 2025 |

|---|